Forget needle and thread. These days, Canadian designers are just as likely to employ advanced computer software and complex chemistry to create their collections. Globe Style visits three studio-labs for a look at their latest experiments.

Stitch hits

Marrying heritage looks with high technology distinguishes Montreal-based Breed Knitting’s men’s wear.

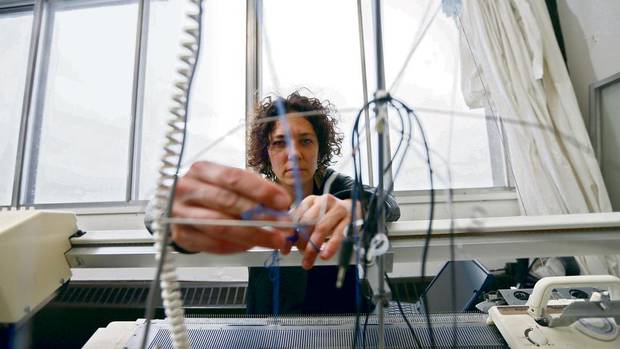

“This season, we worked on taking what is traditionally woven and recreating it in a knit,” says textile specialist Frédérique Sarrazin, one half of the duo behind Breed Knitting, the Montreal men’s-wear brand.

Sarrazin and her partner, designer Ariane Michaud, are sitting in their open-concept studio in the concrete high-rise they share with a mix of fashion-industry players, filmmakers, photographers and fine artists in the heart of Mile End, the city’s old textile district.

Artisanal aesthetic

Although they’ve left behind the jacquard weaves of their previous collection, the pair is dedicated to preserving the artisanal aesthetic that has been winning over gents (and the ladies who love to steal their clothes) since the label launched in 2012.

“We’re really inspired by traditional work wear right now, so we looked into miners’ uniforms a lot,” Michaud, 28, says by a wall of black-and-white photographs of blue-collar workers in Henley shirts, boxy jackets and peaked helmets.

Those period references get updated in a computer program called DesignaKnit, which Sarrazin, 38, uses to draft patterns such as herringbone, houndstooth, basket weave and waffle. Often, designers work with lengths of wool that incorporate such designs into their weaves, but rendering them in a knit adds a chunky, three-dimensional quality to the motifs. Once their patterns have been drafted, Sarrazin and Michaud input them into industrial knitting machines. The result is an aesthetic that’s both nostalgic and contemporary, including pieces such as fine merino-wool tees, crewneck sweaters and, their coup de coeur, a fully knitted slim-fit suit. – Janna Zittrer

Print mastery

Toronto clothing designer Sarah Stevenson uses digital tools to transform her sketches into patterns both precise and pretty.

Picture a contemporary fashion designer’s studio. Does it look like a warehouse full of dress forms draped in muslin and boards hung with spools of thread in every imaginable hue? The new reality is a bit more high-tech than that.

Sarah Stevenson is more likely to spend her day hunched over a Wacom drawing tablet than a Juki sewing machine. The Toronto talent, whose 15-piece collection for Target hits stores on March 23 (prices range from $24.99 to $59.99), creates floral prints with a blend of artistic acumen and technical savvy.

Inspiration

“I do everything by hand first,” says the 33-year-old, who finds inspiration for her flower-motif watercolours in the cherry blossoms and magnolia trees that grow in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, near her midtown studio and flat. After importing her painted images into Photoshop, she manipulates them to create bold patterns that are printed on bolts of silk. A posy, for instance, is made more saturated, then repeated to create a dense field of orange colour. “The digital part takes a long time,” Stevenson says. “I think a lot about how the print will hit the body.”

For the Target lineup, she placed two cascading bands of red-and-blue blooms down the sides of a white tunic (pictured on the front page) and lined up irregularly sized stripes of orange-and-indigo petals on a cocktail dress. “I get nervous if things don’t feel right,” she says of her infatuation with symmetry. “I love working digitally because it’s so precise.” – Andrew Sardone

Testing limits

For British-based rule-breaker Steven Tai, laser cutting and silicone trim are all in a day’s experimentation.

In a few weeks, Steven Tai will settle into proper studio space in north London. But for the past year and a half, the chronically experimental 29-year-old designer and his team have been working out of a messy but efficient apartment. Tai’s technically advanced collection – the standout pieces in this season’s lineup have been intricately silkscreened, then laser cut – is produced at a small factory in nearby Bethnal Green. But this is where all the creative development takes place.

“It’s a half lab,” says Tai, who grew up in Vancouver. “The messiness makes it feel like a painting studio, but then all the tools we have are completely bonkers.”

Creative process

Sometimes, his creative process can be ultra-low-tech, like when Tai decided that a Lurex fabric had too much sparkle for certain parts of a coat and his team picked out the sparkly threads by hand. On the more high-concept side, his spring collection explores the idea of pixelation by layering and bonding sliced-up fabric printed with images of the Eden Project, an eco-tourism site in Cornwall, on skirts and shirts.

“Technology is something we naturally integrate into the way we work,” he says, citing a recent experiment: casting ribbed trim for oversized sweatshirts in silicone. Tai relies on these scientific trials to spark innovation in his work. But, he adds, “I don’t want to be completely meticulous. The spontaneity would disappear.” – Amy Verner