The demogorgon—the faceless demon that haunts the Netflix series Stranger Things—seems menacing at a distance, but would it be scary up close? This was the question that dogged Julien Héry, a supervisor at the Montreal visual-effects studio RodeoFX, in the spring of 2020.

In the first three seasons of the show, the demogorgon played a relatively minor role. The series creators, Matt and Ross Duffer, had kept the creature mostly in the shadows, where, thanks to its lanky but hunched body, it cut a fearsome, Nosferatu-esque figure. Now the brothers wanted to bring it into the light. In season four, it would spend less time lurking and more time running, jumping and devouring. (The creature may not have a face, but it has one horrible face-size mouth.) The production team had commissioned RodeoFX specifically for the new season, which meant Héry and his colleagues had to get the demogorgon ready for its starring role. “I had to imagine the monster in every situation in which it could find itself,” says Héry.

He quickly realized that it would look ridiculous in a fight. It had a double knee, which would seriously impede mobility. Its hands were like talons—all fingers and no palms—making them far too brittle to do any real damage. And, like James Corden or Big Ed from 90 Day Fiancé, the demogorgon had a little neck. You couldn’t imagine it swivelling its head in all directions.

But there was a bigger problem. The monster just seemed…dated. It had visible wrinkles, sure, but the resolution on the skin—what industry people call “the texture”—was much less detailed than it could have been. “The work was good for the time,” Héry concedes, by which he means 2019, another era entirely.

In the old days, filmmakers bewitched and terrified audiences with paint, prosthetics and puppets. Today, they draw up 3D digital images, which they bring to life using simulation algorithms and key-frame animation. Visual effects (or VFX) is a never-ending game of one-upmanship. Each year, central processing units for computers get just a little bit faster. Faster CPUs mean that artists can render digital images with fewer delays. Fewer delays mean more images per workday. More images, in turn, mean more opportunities for iteration—the painstaking, trial-and-error process that enables monster-makers like Héry to craft the veiniest, gnarliest, most terrifying creatures imaginable. If they don’t put in the work every day, as a matter of course, their competitors will.

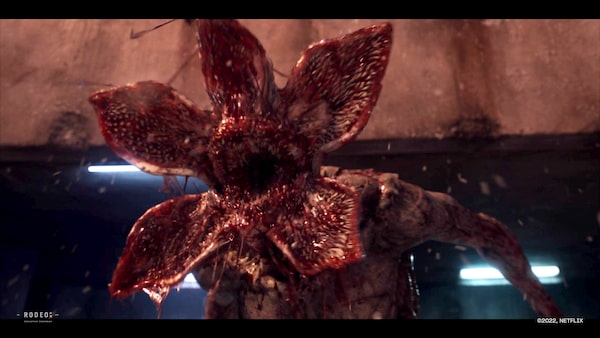

The demogorgon emerges from the shadows in scene from season four of Stranger Things (2022).

Over a period of two years, Héry and his 17-person team created a better demogorgon. They gave the monster a stronger, more physically dynamic body. They adorned the skin with a maze of sinews and scars, making it as marbled as uncooked prime rib. They created short animated demos, in which the demogorgon rears and pounces and slashes. Then they analyzed the movements to confirm that the creature never came off as silly. They even made sure that the saliva dripping from the demogorgon’s maw had exactly the right level of gooey viscosity. “We analyzed everything,” Héry says.

They were after the same goal that everyone in their business is chasing—plausibility. Which is weird, since demogorgons don’t actually exist. This is the paradox of VFX: The aim is to create fantastical creatures and improbable spectacles that nevertheless seem real. Few of us have witnessed an aerial bombardment or a skyscraper blowing up, and none of us has encountered a gnashing, spittle-flecked demon from hell, but when we see these things on screen, we know when they look right. And we know when they don’t.

What’s more, our tastes are getting ever-more discerning. In 1977, people who saw the first Star Wars film were said to have ducked during the opening scene to protect themselves when the Imperial Star Destroyer first slid into view. Today, we chuckle at how corny the whole sequence appears. If someday, RodeoFX delivers shoddy works for one of its clients—a roster that includes Netflix, HBO, Amazon, Apple, Universal, Paramount, Warner Bros., Sony and Disney—we’ll laugh at them, too.

But they’re not in the business of being laughed at. “Reputation-wise, I’d say Rodeo is already in the top 15 or 20 VFX companies worldwide,” says Sébastien Moreau, its founder and CEO. “My goal in the next decade is to get us into the top five.”

This isn’t just a matter of ambition; it may also be a matter of survival. Last year, the global market for VFX likely exceeded US$10 billion. Much of that money wound up in Canada, primarily Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal, which employ thousands of VFX artists between them. (A credible estimate puts the number at well over 15,000.)

In the early 2010s, Rodeo started taking on commissions for creature work – including some wallowing hippos in The Legend of Tarzan (2016) – treating the opportunities as chances to prove their capabilities.

But everyone expects tougher times ahead. New technologies—not just faster CPUs, but also advances in artificial intelligence—are likely to shake up the industry, giving scrappy startups a potential edge on incumbents like Rodeo. A market correction also seems overdue. Movie theatres haven’t bounced back from their pandemic-era dip. And while streamers saw massive growth during COVID-19—enough to offset the decline of cinemas—they, too, are now getting skittish. Last year, Netflix slashed its budget by US$300 million and did something it has never done: reduced its offering of original shows. Executives at HBO Max, Amazon Prime Video and Disney+ all laid off a sizable chunk of their staff.

The industry is also enduring a hangover from recent labour disputes. In 2023, for the first time since 1960, both screen writers and actors went on strike in the same year. At 148 and 118 days respectively, the two union actions were among the longest in U.S. motion picture history. Grievances included pay rates (both writers and actors claimed that streaming services were low-balling their wages) and the rise of AI: writers worried about having their work outsourced to robots, whereas actors feared that studios might produce digital replicas of them without permission or compensation. The delays have been costly. Last year’s productions, of course, are this year’s post-productions. And so the market for available VFX work is smaller today than it has been in ages.

Demand is not only shrinking, though; it’s also changing. A series of recent box-office flops—The Flash, Blue Beetle, The Marvels—suggest that the superhero craze that drove the VFX market is finally ending. Nobody knows what will replace it. More videogame adaptations? Barbie spin-offs? Taylor Swift concert films? In this uncertain climate, Moreau would rather hedge his bets than make predictions. “The best way to thrive in the next few years,” he says, “is to be good at absolutely everything.”

Canada has a strange relationship with the film industry. We don’t often produce world-famous content. And beyond a handful of people with the last name Cronenberg, we don’t have a large roster of internationally renowned directors. Many of our homegrown directorial talents—James Cameron, Jason Reitman, the scandal-plagued Paul Haggis—have migrated to points south.

But if the U.S. is where big new films are conceived and financed, Canada is where much of the work gets done. Our arrangement with Hollywood is a bit like our relationship with Ford and General Motors. We may not own the means of production, but we perform a lot of skilled labour. “When it comes to the large-money film ecosystem, Canada plays a vendor role to its American colleagues,” says Kevin McGeagh, head of virtual productions at Toronto-based film studio The Other End. “Even movies that are filmed in Canada with predominantly Canadian talent are still usually American under the hood.” As Canadians, we get paid to pitch in. The work is good. The jobs are well compensated. But the projects aren’t ours. And neither is the intellectual property.

There are many reasons why a California-based studio might want to outsource its VFX contracts to Canada: our proximity to the U.S., the lower value of the Canadian dollar, and a federal incentive system, in place since 1996, whereby a studio can get a rebate on 12% of its labour expenditures, above and beyond whatever local rebates the provinces add on. There’s also a sense that Canadians know what they’re doing. Some of the most widely used VFX software applications—the animation program Houdini, the 3D-image generator Maya—were created in Canada in the 1990s. VFX, in short, is a homegrown industry, nurtured today by dozens of trusted schools, including Sheridan College, Seneca College and the Vancouver Institute of Media Arts.

Montreal is particularly attractive for U.S. producers, since it has a lower cost of living—and therefore lower salaries—than almost any creative-class city on the continent. And Quebec’s incentives are geared toward VFX specifically. If you hire a Quebec resident to do anything involving animation, computer graphics or green screens, you can get a rebate on 36% of your labour outlays. Unsurprisingly, the province has become a VFX hub, home to more than 40 such companies.

Sébastien Moreau bluffed his way into his company’s first gig. Now RodeoFX is a top visual-effects studio.

Moreau started his career in the city as a compositor—an artist who places digital elements (so-called “assets”) inside live-action shots. This work is more difficult than it might seem. If you simply Photoshop a computer-generated helicopter above a live-action scene of a helipad, it’ll look wrong in every possible way. To properly integrate a CGI helicopter, an artist, using a specialized software application like Flame or Nuke, must ensure that the lighting on the vehicle perfectly matches the scene, that the wind and dust are swirling the right way, and that the movement of the vehicle complements the action on the ground. If characters are looking up, they’d better be looking, without exception, in exactly the right place.

Moreau was good at this work. So good that he got hired by some of the biggest VFX companies in the world: California’s Industrial Light and Magic, founded by Star Wars director George Lucas, and New Zealand’s Weta FX, co-founded by Lord of the Rings creator Peter Jackson. But he always aspired to start a company of his own. In 2006, he got approached by Eric Brevig, a VFX specialist who was about to direct his first Hollywood film, an adaptation of Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth. Brevig asked Moreau if he could recommend a VFX house in Montreal. “I told a white lie and said, ‘I’m starting my own company there,’” Moreau recalls. Then he did it. “Journey was a big project,” Moreau recalls, “but I knew Brevig would give me a little piece of it.”

That’s how Rodeo got its first client. It got its name from Rodeo Drive, the L.A. shopping corridor known for its high-end fashion boutiques. Moreau wanted his studio to have a boutique sensibility. It wouldn’t be the biggest player in VFX, he reasoned, but it would do the most challenging, specialized tasks.

That isn’t how things started out, though. The depressing reality of VFX is that much of the work is fairly rote: adjusting lighting, adding snow to winter scenes, editing out the stunt double’s face, sharpening the leading man’s abs, changing the way a falling boulder lands so that it doesn’t bounce as if it’s made of foam (which, of course, it is). Rodeo got these kind of straightforward jobs along with more specialized gigs in compositing and matte painting—the business of fitting out images with realistic backgrounds. (If a director shoots a battle scene in studio, the matte painter will create the craggy mountains in the distance, perhaps by combining and touching up pre-existing photographs.)

To get the really good work, the company needed to prove that it could handle creatures, which are among the toughest challenges that VFX artists face. A creature is basically a photorealist computer animation, a cartoon that doesn’t look cartoonish. Creating a good one requires a team of graphic-art specialists: concept artists who draw the initial drafts, modellers who build it (virtually) in three dimensions, texture artists who work on skin, groomers who make the hair look real, riggers who determine how the joints and muscles work, animators who bring the beast to life, and compositors who integrate it into its environment.

In the early 2010s, Rodeo started asking clients for whatever bits of creature work they could offer. The company treated every tiny commission—a pickled monster brain in Pacific Rim, some wallowing hippos in The Legend of Tarzan—as an audition, a chance to prove their capabilities. “We didn’t ask, ‘How much is each contract going to cost us?’” says Jordan Soles, a senior vice-president at the company. “We asked, ‘What does it allow us to do?’”

Then HBO came calling. The network had the most coveted VFX gig: Game of Thrones, the first-ever TV show with cinema-worthy special effects. To get work on the series, Rodeo had to endure a near-literal trial by fire. “The producers gave us a video depicting real fire and told us to digitally recreate it,” Moreau says.

Fire is devilishly hard to simulate. It’s a roiling mix of translucent colours. It moves quickly. And it distorts the surrounding light. Even big-budget films tend to botch their fire effects. (Check out the scene in Sony’s No Hard Feelings in which Jennifer Lawrence spontaneously combusts and what look like flame emojis start emanating from her body.) The Rodeo team did a near-perfect job, though. “In the end, the producers couldn’t tell which was the original and which was the simulation,” says Moreau.

That triumph led to a slew of ever-more-challenging GoT commissions: a statue tumbling down the side of a pyramid in season five, for instance, and the starkly beautiful collapse of the 200-metre ice wall in season seven. For that feat, the team divided the wall into pieces and created simulations to guide the movement of each chunk of falling debris. The work was painstaking and burnout-inducing. But the result was spectacular: an otherworldly spectacle shot with documentary realism, BBC’s Planet Earth but set in Westeros.

The collapse of a 200-metre ice wall in season seven of Game of Thrones (2017).

The project established Rodeo as one of the most sophisticated VFX houses in the world. Soon they were getting all the exciting jobs. They staged a chase scene in Paris’s Place de l’Étoile in John Wick: Chapter 4. They crafted breathtaking panoramic shots of Middle Earth in the Tolkien spin-off The Rings of Power. And alongside Denis Villeneuve, Moreau’s old Montreal buddy, they created the arid, fascistic world of Arrakis, the desert planet on which the Dune films are set.

They were charging competitive rates, and clients were willing to pay. In 2021, Stephen Rosenbaum—the studio VFX supervisor for Apple TV’s World War II miniseries Masters of the Air—realized that the production was becoming more complicated than he’d expected. There were the predictable challenges: the intricacy required of the show’s many aerial stunts, the pressure to perfectly reconstruct each period detail, from the flight formations to the airplane nose cones, in order to appease the history nerds on Reddit.

But the situation had been made worse by COVID. Instead of filming on location at a former POW camp in Europe, the team had to create a miniature camp on an abandoned airfield and then build out the environment in post-production. “Once shooting was completed, four army barracks had to somehow become 100,” says Rosenbaum. “A hundred extras had to become 10,000.” Rosenbaum had planned to hire mostly small, inexpensive VFX studios, but he soon realized that only “big gun” vendors could handle such an expansive undertaking. “Rodeo was one of a few VFX houses in the world that could manage such a large, diverse body of work,” he says. It was the company you hired when you weren’t sure what else to do.

At Rodeo FX, not every effect is created digitally. For blood splatter, VFX photographers Jean-François Massé (right) and Antoine Bordeleau fire red liquid through a pipe.

It had gotten that reputation, in part, through a willingness to experiment. In Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald, there’s a character who disintegrates into a cluster of glowing particles. To make that sequence, Rodeo hired a dancer to perform on camera. They used her movements to guide their simulation algorithm. She doesn’t appear in the sequence, but the particles follow the motion of her limbs, imbuing the scene with balletic lyricism.

Sometimes, though, the team dispenses with simulations altogether. Unlike most VFX companies, Rodeo has a practical-effects stage—a room roughly one-and-a-half times the size of a squash court, with a wraparound green screen—where it creates spectacles the old-school way. Clouds are made with dry ice or a smoke machine. Blood spurts are replicated by spitting red liquid through a tube. The shaggy, elephant-size spider that haunts Villeneuve’s existential horror film Enemy is an actual tarantula, filmed closely and then blown up. In the satirical superhero show The Boys, there’s a sex scene that goes horrifically wrong: A woman, empowered with heroic strength from having ingested a mysterious compound, ends up crushing a man’s head beneath her pelvis until (whoops!) his brains pop out. Rodeo made that sequence with an actual veal brain. They bought it from a butcher shop and blasted it through an air compressor.

But do we still crave these spectacles? Are we still willing to pay to be grossed out, charmed or dazzled? Last summer, everyone talked about Barbenheimer. Less talked about were the many box-office disasters: the Buzz Lightyear spinoff that resulted in two Disney executives getting fired, the Expendables sequel that not even 50 Cent could save, and the Adam Driver dinosaur caper whose name you don’t even remember. Two blockbusters in one weekend? That’s news. Another Hollywood flop? That’s business as usual. “Hollywood feels like it’s lost the formula,” says Lachlan Christie, an executive producer at Rodeo. “The studios are terrified of spending a ton of money and getting absolutely burned.”

There are other signs of peril in the VFX industry: budget cuts at the streamers, the craze for homemade short-form videos, which may be eclipsing long-arc storytelling, and the rise of AI, which has democratized tasks that used to require skilled labour. Rotoscoping, for instance—the work of editing out bits of green screen that cling to a character’s body—was once a reliable, if tedious, job that sustained VFX houses between more exciting projects. Now machines can rotoscope pretty well. They can also produce half-decent CGI concepts. Ask an AI generator like Midjourney or Runway to depict, say, a man on a beach staring at the sun, and it’ll produce a decent first draft. Humans were once paid for work like this.

When asked if they worry about the future, the executives at Rodeo all respond with cheery optimism: Sure, challenges lie ahead, they concede, but the company will be fine. “People are not going to want to have their VFX look less good than before,” says Christie. “We can survive by being a high-quality boutique rather than a mass-quantity shop.” Premium work, in other words, is the best hedge against irrelevance.

It’s a defensible argument. Book and magazine publishers have good reason to fret about the decline of reading, but filmmakers needn’t worry that watching, the West’s most beloved pastime, is somehow declining, too. In the decades to come, people will still consume vast amounts of motion-picture content on screens of varying sizes. Some of that content will require effects. And the most competitive studios will still get work, even if the overall market is smaller. For elite VFX houses, the worst-case scenario is far from dire.

And yet, Rodeo does seem to be insulating itself against potential market disruptions. In 2012, it launched an advertising and experiences division, specializing in commercials, viral marketing campaigns and immersive installations, like the Stranger Things exhibit at Cannes 2023, in which a holographic demogorgon jumped out at unsuspecting festivalgoers.

A VFX-expanded POW camp in Masters of the Air (2024).

The Stranger Things Demogorgon (2022). In 2012, RodeoFX launched an advertising and experiences division, specializing in commercials, viral marketing campaigns and immersive installations, like the Stranger Things exhibit at Cannes 2023.

Commissions like these give Rodeo a chance to court new markets and, critically, to experiment with novel techniques. The new division recently tried out deep-fake technology on an ad for Quebec milk producers. And when designing a concert experience for the French-Lebanese pop star Mika, it created video installations featuring a mix of human- and AI-generated images. The clients are often smaller than Hollywood studios and more open to experimentation, too. Many, says Solène Lavigne Lalonde, vice-president of advertising services and marketing at Rodeo, “are enthusiastic about integrating cutting-edge technology into their campaigns.” Her division is a laboratory, a place to try out approaches that may eventually migrate to the film and TV world.

Rodeo’s most interesting new venture, however, is also its least auspicious: Canary, a 12-minute animated short about a child mine worker, Sonny, in 1922, who takes care of a caged canary. The bird gets lowered into the shaft ahead of the men to warn them of poisonous methane gas. Both it and its keeper dream of life above ground.

Rodeo didn’t just create the film. It commissioned and produced it, too. Which means the company owns the intellectual property. “Our long-term goal is to move into original animated content,” says Moreau. It’s not hard to see why. A prized piece of IP is a rarity, but it’s more valuable than anything else Rodeo could produce. By some estimates, Disney generates US$3 billion a year simply by licensing out the Mickey Mouse trademark. That’s a stable revenue source in an uncertain business. An IP breakthrough would make Rodeo an anomaly among Canadian VFX studios—a creator rather than a vendor, an owner of a coveted asset, not just a hired gun.

In Canary, Sonny teaches the bird to play dead. Each time it appears to die, the panicked miners ascend to the surface, giving the boy and his avian pal a few precious minutes of freedom. The duo are stuck in an industrial system they don’t control. But they hope, through guile and creativity, to escape to better things.

More from this issue of ROB magazine:

-

Cover story:

Reigning cats and dogs: How Pet Valu monetizes our unconditional fur-baby love -

Editor's Note:

Toronto has fallen into disrepair. How is Olivia Chow going to fix it? -

Best Executives 2024:

Out of the spotlight: Hailing the unsung executives who move their companies forward -

Big Idea:

Artificial intelligence is changing how companies snoop on each other

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.