Alexander Lysakowski/The Globe and Mail

When Alexandre L’Heureux became CEO of WSP Global Inc. in 2016, there was a minor concern at the back of his mind. Even though he’d been with the engineering consulting firm for close to six years by that point, he worried that employees wouldn’t embrace him as the leader of the company. L’Heureux had been the chief financial officer, a numbers guy—not an engineer by training.

As it happens, he once tried to be an engineer. Growing up on the south shore of Montreal, L’Heureux, now 50, harboured a fantasy of working for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, otherwise known as NASA. The dream didn’t last long. “I discovered very early on that I found engineering very boring,” he recalls. “I said, ‘There’s no way I’m doing this.’” L’Heureux pursued accounting instead, embarking on a career that led him to Deloitte, a hedge fund in Bermuda, a private equity firm and, finally, ironically, to the C-suite at WSP, leading a company of engineers.

But L’Heureux’s mix of skills was exactly what WSP needed at the time. “When you start to get to the scale we’re at now, the qualities you want in your leader are actually not engineering,” says Christopher Cole, chair of WSP’s board. “They are strategic skills, they are financial, they are risk analysis. I’m an engineer, so I say that with some reluctance.”

It turned out employees didn’t care about L’Heureux’s lack of formal training, either. The market, however, was not so keen on the day of his promotion. “Our stock price, if I’m not mistaken, lost 2% or 3%,” the CEO says.

Since then, the market has come around on L’Heureux. And quickly. Shares in WSP have surged more than 340% since his appointment, employee headcount doubled to 66,350, and the company has far surpassed rival SNC-Lavalin Group in terms of market cap. (WSP is worth $20 billion on the TSX, compared to just $4 billion for SNC.) Much of the growth is due to L’Heureux’s approach to acquisitions, honed over some 80 deals since he joined as CFO in 2010—carefully considered and price conscious—something that isn’t taught at any engineering school.

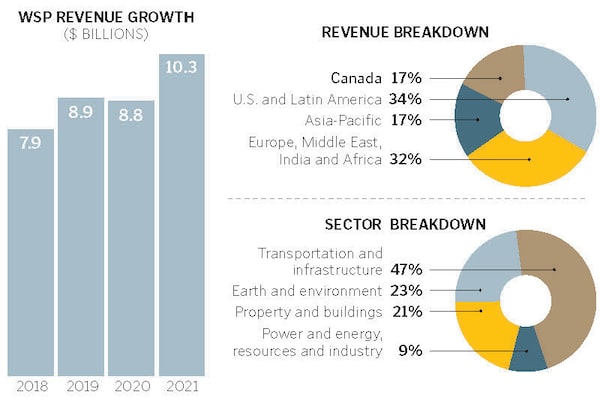

Perhaps most notably, WSP has expanded its international footprint. Only 17% of WSP’s revenue is derived from Canada, according to the company’s 2021 annual report, with the largest chunk coming from the United States and Latin America, followed closely by Europe, Africa, India and the Middle East. WSP’s catalogue of work is as deep as it is eclectic: project management of the renovation of Centre Block on Parliament Hill; a flood-control plan for a river basin in China; a net-zero strategy for a hospital in the United Kingdom; assessing bat habitats in Ontario and Quebec; developing and evaluating congestion pricing for the Swedish Transportation Administration; and figuring out how to reduce vortex shedding—when wind causes a building to vibrate—at one of the tallest residential condos in the world, located in Manhattan.

The reputation WSP enjoys with both analysts and investors nevertheless creates high expectations, with pressure on L’Heureux to deliver consistent growth, expand margins and not bungle the integration of its largest-ever buy—the $2.3-billion purchase of the environmental and infrastructure division of British company John Wood Group earlier this year.

Strategist of the Year: How Rowan Saunders pulled off the second-largest IPO in Canadian history

Newcomer of the Year: Sophie Brochu signed Hydro-Québec’s biggest export deal ever

Innovator of the Year: How Ann Fandozzi is dragging Ritchie Bros. Auctioneers into the digital age

WSP grew out of a boutique engineering and construction firm in Quebec called Genivar, which was itself initially formed through the merger of two local companies founded in the late 1950s. Genivar mostly stayed confined to its home country, working on projects such as the renovation of B.C. Place in Vancouver, completed in 2011. The following year, the company purchased WSP Global, then a British professional services firm, helping set the stage for the global expansion of the past decade. (Genivar renamed itself WSP in 2014.)

Over the years, the company moved into consulting services and away from fixed-price construction projects, which are prone to delays, cost overruns and losses. “They were very smart to essentially get out of the [construction] business,” says Dimitry Khmelnitsky, an analyst at Veritas Investment Research. Meanwhile, SNC-Lavalin reports a massive loss every few years, he points out.

WSP is benefiting from a few larger trends, too. Governments in Canada, the U.S., the United Kingdom and Australia are planning to invest billions of dollars in infrastructure over the next few years, while countries around the world are trying to decarbonize their economies—retrofitting buildings, developing renewable energy projects and so on—which requires the kind of environmental consulting expertise WSP provides.

But the trends alone aren’t enough to raise WSP’s fortunes. Everything still comes down to execution, which is where L’Heureux comes in. His time as an accountant at Deloitte in the 1990s is more influential on his thinking than one might expect. The accounting and consulting world is essentially dominated by the four major firms, and the engineering and professional services space looks to be heading in the same direction. It’s highly fragmented, with an untold number of boutique and mid-size firms poised for consolidation. “It’s not by accident that I’ve spent an enormous amount of time looking at what I believe are the most successful professional services firms in the world,” says L’Heureux. “How are they operating globally? How could we replicate something?”

Global growth inevitably means acquisitions, and L’Heureux has a simple framework for buying a company. To start, there has to be a good reason for the deal, and a potential buy must fit within his three-year strategic plan for the firm. Price is crucial—WSP has a track record of staying disciplined, analysts say—as is culture fit. Indeed, in some cases, L’Heureux has spent years talking to executives at other firms to understand their values and motivations. Engineering is a vocation, he points out, not unlike medicine or science. “If I don’t find a sense of this vocational mindset,” he says, “and they’re there for the money or because of other reasons than building a better tomorrow, we’re not going to do the deal.”

Lastly, L’Heureux has to be convinced he can sell the deal. “I need to look at myself in the mirror, and I imagine myself on stage in front of all of our employees,” he says. He asks himself whether he can explain the merits of the transaction. Sometimes he can’t. “A number of times, I have passed on superb deals on paper,” L’Heureux says, describing the exercise as one last “sanity check.”

This past August, when WSP announced a deal to buy a British firm called RPS Group, the sale seemed to check all the boxes. RPS conducts a lot of work in the environmental sector—an area in which L’Heureux wants to grow, as per his latest strategic plan—particularly in water and wastewater management, where WSP is underrepresented. Its offer valued the company at just under $1 billion—not an unreasonable price, even if some analysts noted it was on the loftier side.

But then another bidder emerged. U.S. rival Tetra Tech Inc. put forward a deal with an even richer valuation attached to it. L’Heureux wasn’t surprised another bidder was waiting in the wings, and his next step was obvious. RPS was fully valued, in his opinion, and there was no good reason to pay more. “You need to stay true to your DNA, to discipline,” L’Heureux says.

Just because the decision was obvious doesn’t mean it was easy. L’Heureux had already spent time convincing the board it was a good deal. Now he had to explain why the company should walk away. Cole says L’Heureux’s decision-making process on the deal is typical of him as CEO. His gut instinct was not to get into a bidding war, Cole recalls, but L’Heureux then spent the time to test and prove his intuition. “He returned with a very reasoned response to the board why the intuition was now validated in his mind,” Cole says.

“It’s not by accident that I’ve spent an enormous amount of time looking at what I believe are the most successful professional services firms in the world. How are they operating globally? How could we replicate something?”

— Alexandre L'Heureux

L’Heureux figured that while the purchase would expand WSP’s capabilities in a few areas, it wasn’t crucial. Other opportunities would arise, and the company already had its hands full integrating some 6,000 employees from the environmental division of John Wood, a deal that closed in September.

That ability to absorb a company into the larger entity is one of those things L’Heureux maps out beforehand. It’s partly why he frets so much about culture, but the structure of the organization is equally important. WSP is arranged by geography, not by business line. There’s a CEO for Asia, for example, but no CEO of transportation infrastructure. Acquiring a company arranged differently would require immense reorganization of people and resources, so L’Heureux looks for firms that can be absorbed with minimal fuss. He describes himself as “beyond hands-on” as a CEO, and the company has no chief operating officer so that he can have a direct relationship with the executives running each division.

L’Heureux will need to keep in touch with those leaders in the months ahead. Whereas macroeconomic factors have worked in WSP’s favour in recent years, the risk of recession is looming, and inflation is driving up the cost of building projects. About half of WSP’s work is for the public sector, according to Khmelnitsky, which is better insulated in a downturn. But private-sector clients are more likely to postpone projects, which could be problematic for WSP since its work tends to be short-term and therefore requires a constant flow of new orders.

For his part, L’Heuruex says WSP is lean, especially after cutting about $100 million in costs during the early months of the pandemic, and has little in the way of fixed costs today. Plus, the company’s order backlog is still growing. As of the second quarter of 2022, it stood at a record $11.4 billion, a 19% jump from the same period last year. Given WSP’s strong balance sheet, economic uncertainty could also present an opportunity for the firm to strike more deals, says RBC analyst Sabahat Khan. “Recall that WSP has not been shy about undertaking sizeable acquisitions during past periods of uncertainty,” Khan wrote in a recent note. During the depths of the pandemic in December 2020, for example, WSP announced a deal to buy environmental consulting firm Golder Associates.

A potential recession and inflation are not even at the top of L’Heureux’s list of worries. He’s more concerned about preserving the culture at WSP. Not surprisingly, he draws an example from the accounting world: Arthur Andersen, which collapsed amid scandal two decades ago. “They got cocky, they got complacent, and they thought they were better than others,” he says. “We need to make sure we remain humble. The day you think you’re too big to fail, that’s when problems emerge.”

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.

Joe Castaldo

Joe Castaldo