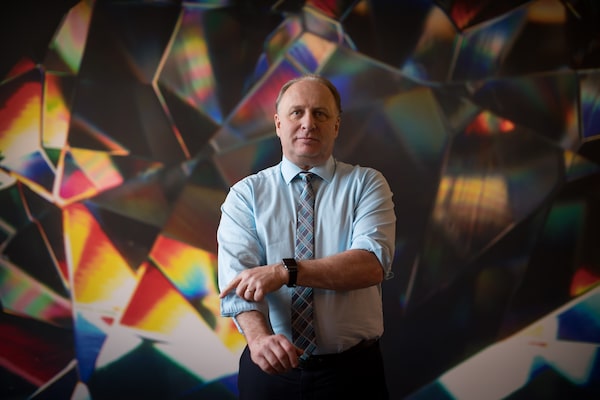

Andrew Gemino, associate dean of graduate programs at Simon Fraser University’s Beedie School of Business, pictured in the Segal Graduate School of Business building on Granville Street in Vancouver on Mar. 5.Darryl Dyck/The Globe and Mail

When Bob Joseph began working in Indigenous relations 25 years ago, the federal government’s advice to businesses for consulting with Indigenous communities went as follows: Send a letter. Wait 30 days. No response, proceed with permitting.

Although there was a requirement for Indigenous consultations on paper, discussions often didn't really begin until after a project was planned and moving into the permit phase.

“That just triggered acrimonious conversations,” says Mr. Joseph, the founder and president of B.C.-based Indigenous Corporate Training (ICT) and a member of the Gwawa’enuxw, one of 18 tribes in the Kwakwaka’wakw Nation in British Columbia.

Nationwide protests over Coastal GasLink’s pipeline through B.C., over the objections of some members of the Wet’suwet’en Nation, have put the spotlight on the relationship between corporate Canada and Indigenous communities.

“It’s definitely a pivot point in Canadian history that will fundamentally change how governments do this kind of work,” says Mr. Joseph, who founded ICT in 2004 and has written several books including 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act and Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples (which he co-wrote with Cynthia Joseph).

With the Wet’suwet’en land dispute in the news, business is booming, he says. His blog received 145,000 visitors last month.

“That tells me there’s a real thirst for knowledge from people. They are trying to learn,” he says.

Simon Fraser University’s Beedie School of Business offers a one-of-a-kind executive MBA in Indigenous business leadership.Darryl Dyck

But there is a huge gap in opportunities for corporate leaders to learn, which business schools are aiming to fill.

Simon Fraser University’s Beedie School of Business offers a one-of-a-kind executive MBA in Indigenous business leadership. The course work includes case studies of First Nations businesses and entrepreneurship as well as cultural practices, including smudging and elder knowledge sharing.

There’s also a course in which students visit an Indigenous community and do exercises and have conversations with its residents.

“Content alone is not the way to have this material understood. You have to actually experience it,” says Andrew Gemino, Beedie’s associate dean of graduate programs.

There have been five cohorts of the MBA program, which will soon have 92 alumni, Dr. Gemino says. About 90 per cent of the class are Indigenous students; the other 10 per cent aren’t, but are interested in understanding the Indigenous perspective.

Awareness of Indigenous issues and their impact on business is also now part of all MBA programs at Beedie, Dr. Gemino says, and has changed the way the school operates.

“Now, at pretty much every event we have, we talk about the unceded territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh nations,” he says. “We understand and we’re much more aware of our relationship with the nations.”

While Indigenous relations are applicable to doing business around the world, B.C. is in a unique situation, having few signed treaties, Dr. Gemino says. Natural resource development in B.C. is wrapped up in Indigenous title and rights.

“As a business person, you need to understand that perspective, that history, and be aware of it,” he says.

Beedie is hoping to move the EMBA program east, offering it closer to home for members of Indigenous communities in other parts of the country, such as Ontario. The goal is to expand in 2021, if the right partners are found.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s report, released in 2015, includes several calls to action in education. Finding the right faculty and staff to fulfill those recommendations, though, poses a challenge.

“There is a huge lack of resources … being Indigenous peoples who are able to educate and communicate with others in a university setting,” Dr. Gemino says. “There’s a huge demand for highly skilled Indigenous people. We’re trying to develop them as fast as we can.”

The Rowe School of Business at Dalhousie University is an example. Linda Macdonald, who teaches business communications at Rowe, says Indigenous relations are in the school’s curriculum in ethics and leadership courses. There’s also Indigenous content in management coursework and the TransMountain pipeline upgrade project is a case study for business students, she says.

The school would like to expand its Indigenous curriculum but lacks the Indigenous staff and faculty.

“The trouble has been for us that we don’t individually have the background to do this properly,” Dr. Macdonald says. “We are being responsible about it. It’s somewhat slow but it also seems appropriate to do it that way.”

Mr. Joseph of ICT says he believes not just business schools, but all graduate and undergraduate educations should include a mandatory Indigenous curriculum.

“Mining. Forestry. Political science. Health care. It’s hard to think of something that isn’t impacted by Indigenous relations,” he says. “And I have seen people with a little bit of knowledge and ideas make unbelievable inroads.”

Mr. Joseph, who inherited the hereditary chief title of the Gayaxala (Thunderbird) clan, believes it is also making things better for Indigenous communities like his own.

“I really like to think that we can do things in ways where everybody wins. It doesn’t have to be ‘us’ and ‘them,’” he says.