Lynn-Marie Angus is the owner of New Westminster, B.C.-based Sisters Sage, which makes hand-crafted soaps, smudges, salves and bath bombs using traditional ingredients. She recently moved her business online.Alia Youssef/The Globe and Mail

After the year Shopify Inc. has had, you might expect its co-founder and CEO Tobi Lutke to sound a little…cheerier.

Riding a global surge in pandemic-related e-commerce traffic, Shopify – which makes the software used by more than a million merchants to sell their products online – surpassed Royal Bank of Canada to become Canada’s most valuable company. It now has a market capitalization of US$177-billion, making it only the second Canadian tech company, after Nortel Networks, to reach such heights. It raised billions of dollars from stock sales last year and even posted a rare quarterly profit of US$191-million in October on third quarter on revenues of US$767.4-million – nearly double what they were a year earlier. (Revenue in the second quarter nearly doubled, too.) When it reports its fourth-quarter results next week, analysts expect sales to have increased by more than 80 per cent over 2019, to US$909-million.

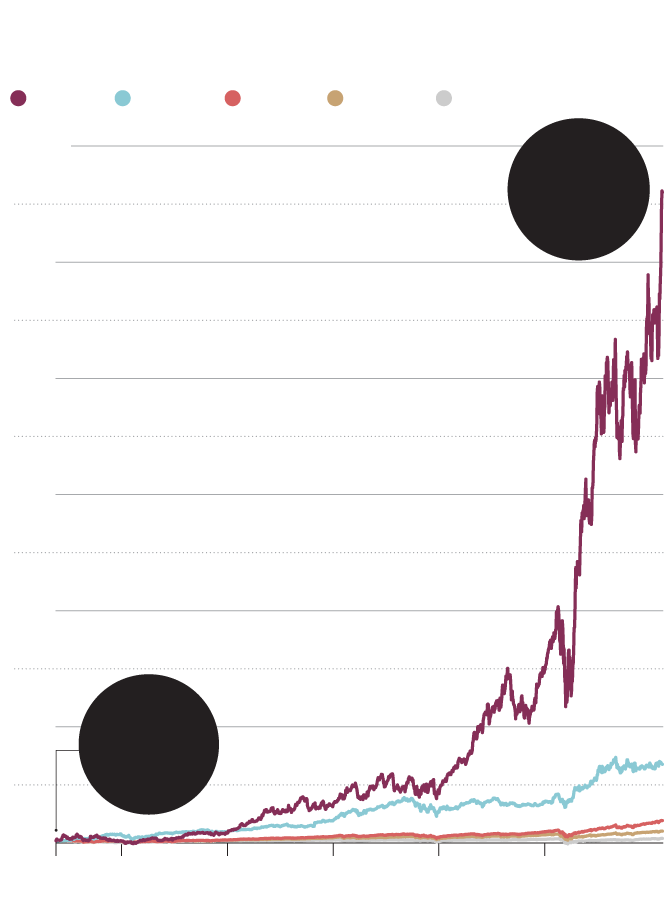

Shopify has outpaced the markets

Percentage change since Shopify’s IPO in May, 2015

Shopify

Amazon

Nasdaq

S&P500

TSX

6,000%

US$1,463.31

Feb. 11, 2021

5,000

4,000

3,000

2,000

US$25.68

1,000

May 21, 2015

0

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: REFINITIV EIKON

Shopify has outpaced the markets

Percentage change since Shopify’s IPO in May, 2015

Shopify

Amazon

Nasdaq

S&P500

TSX

6,000%

US$1,463.31

Feb. 11, 2021

5,000

4,000

3,000

2,000

US$25.68

1,000

May 21, 2015

0

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: REFINITIV EIKON

Shopify has outpaced the markets

Percentage change since Shopify’s IPO in May, 2015

Shopify

Amazon

Nasdaq

S&P500

TSX

6,000%

US$1,463.31

Feb. 11, 2021

5,000

4,000

3,000

2,000

1,000

US$25.68

May 21, 2015

0

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: REFINITIV EIKON

Shopify provided a critical lifeline during the pandemic for merchants that previously had little or no e-commerce presence – and gave established brands like Heinz and Lindt new ways to sell directly to consumers. With total merchant sales now exceeding US$100-billion globally, Shopify has the second busiest e-commerce platform in the U.S., after Amazon. com Inc.

And yet, when asked what parts of Shopify dissatisfy him, Mr. Lutke replies: “Everything.”

The 40-year-old CEO, whose personal net worth now exceeds US$12-billion, is known for his blunt and often brutal assessments of both himself and the company he co-founded in 2004. Three months after its 2015 initial public offering, for instance, he warned staff that Shopify was destined to fail like BlackBerry Ltd. or Nortel unless it improved its mobile offerings.

SHOPIFY VS. AMAZON

(U.S. DOLLARS)

REVENUE

(2020)

NET WORTH

(as of Thursday, Feb. 11)

Amazon

$386.06-BILLION

Jeff Bezos

$189.5-BILLION

Tobias Lütke

Shopify

$12.9-BILLION

$2.86-BILLION

CURRENT MARKET CAP

Amazon

$1.66-TRILLION

Shopify

$178-BILLION

SHOPIFY VS. AMAZON

(U.S. DOLLARS)

REVENUE

(2020)

NET WORTH

(as of Thursday, Feb. 11)

Amazon

$386.06-BILLION

Jeff Bezos

$189.5-BILLION

Tobias Lütke

Shopify

$12.9-BILLION

$2.86-BILLION

CURRENT MARKET CAP

Amazon

$1.66-TRILLION

Shopify

$178-BILLION

SHOPIFY VS. AMAZON

(U.S. DOLLARS)

REVENUE

(2020)

NET WORTH

(as of Thursday, Feb. 11)

Amazon

$386.06-BILLION

Jeff Bezos

$189.5-BILLION

Tobias Lütke

Shopify

$12.9-BILLION

$2.86-BILLION

CURRENT MARKET CAP

Amazon

$1.66-TRILLION

Shopify

$178-BILLION

Now, it seems, it’s time for another overhaul. “I know it works well, but it’s still terrible,” he says of the company’s platform. “It can get significantly better.”

Last fall, he displaced his chief product officer, Craig Miller, who had spent nine years at Shopify, and took on the role himself. At the same time, he ceded day-to-day outreach and operations to president Harley Finkelstein, a natural-born communicator who is a perfect foil for his shy and awkward boss. (Even Mr. Lutke’s own wife, former diplomat Fiona McKean, calls him “an immigrant to the human condition.”)

“I think it’s good for Shopify that I run product every few years,” says Mr. Lutke, a competitive gamer and programming whiz who developed the original software. “This is the time. I don’t think I’ll ever find someone who cares as much about the product as I do. World-class software is what I want you to expect from Shopify.”

In Mr. Lutke’s view, Shopify is trying to catch up to a future that arrived 10 years ahead of schedule, thanks to an accelerated shift to online retailing brought on by the pandemic. (According to DigitalCommerce360, U.S. online sales last year jumped by 44 per cent, to US$861-billion, accounting for 21.3 per cent of all retail sales.) If we’re now living in the e-commerce landscape of 2030, then by his way of thinking, Shopify’s products are a decade out of date. Things he thinks should be getting easier and better – like shoppers no longer having to type in their e-mail addresses and credit card numbers when they order online – “are infuriating to me the way they are. We can make them so much better.”

There’s another reason for Mr. Lutke to turn his full attention to Shopify’s core offering: Amazon is turning its attention to him.

Although the two companies don’t compete head-on – Amazon runs an online consumer marketplace to sell its own goods and those from third-party merchants, while Shopify is used by retailers to run their stores and back-office operations – Shopify’s expansion represents an existential threat to the Seattle-based e-commerce goliath.

As Amazon increasingly sucks up online retail business (and draws criticisms for alleged anti-competitive behaviour), Shopify helps level the playing field for independent merchants. Several, including Gymshark, Allbirds, Kylie Cosmetics and Canada’s Knix, have become major brands that sell through an array of channels – often bypassing Amazon.

In true geek fashion, Mr. Lutke has framed the looming battle with Amazon with a Star Wars metaphor: “Amazon is trying to build an empire, and Shopify is trying to arm the rebels.” He’s a little more prosaic today: Shopify, he tells The Globe, “is literally meant to be an alternative to Amazon.” The entire company was borne from his rejection of the idea, when he was a fledgling e-commerce merchant himself, that he would have no choice but to sell his snowboards through online marketplaces.

Amazon has stated that it welcomes the competition. But Shopify’s success is starting to come at Amazon’s expense, and last year, according to The Wall Street Journal, it struck a “secret” internal task force dubbed Project Santos to figure out how to counter the growing pressure from the Ottawa-based company. (Amazon declined an interview request for this story.)

How will Shopify – which is less than one-hundredth Amazon’s size by revenue and has never really had a serious competitor of its own – fare if the empire strikes back?

Craig Miller was one of just a few Shopify executives at work during the second week of March, 2020, when Italy went into lockdown. The team had been nervously tracking the coronavirus’s progress for weeks, and at that point, he says, “a few of us got it and understood things could get really, really bad.” With Mr. Lutke away for March Break with his wife and three kids, Mr. Miller, the chief product officer, made the call with his colleagues to close Shopify’s offices and send its 5,000-plus employees to work from home.

By the following week, Shopify’s stock was down nearly 40 per cent from mid-February levels, and at the start of April, the company pulled its financial guidance. “Initially,” says Mr. Miller, “there were a lot of concerns the pandemic would be very detrimental to Shopify.”

But this wasn’t the first time the company had faced a global calamity.

When the world tilted into a deep recession in 2008, Mr. Lutke had only recently taken over as CEO after his co-founder, Scott Lake, quit. Times were already lean for the small startup. He was living with his wife’s parents, and he needed his father-in-law’s help to cover payroll. As the credit crisis worsened, he thought Shopify was toast. But then people left unemployed by the sharp downturn started to open online stores using his software, and Shopify discovered its mission: to help fledgling entrepreneurs create a livelihood for themselves. Soon it was one of the top young subscription software companies in the world.

In those early years, Shopify was already distinguishing itself as a brasher, more worldly company than its Canadian peers. At career fairs in the late 2000s, the company – which is based in downtown Ottawa – posted signs reading: “Be Awesome, Don’t Work in Kanata,” a dig at the suburb where most of the city’s tech employers are headquartered. (Mr. Lutke, who is from Germany, once told The Globe Shopify “could be run remotely out of anywhere” – Ottawa just happened to be where he lived.) He was dismissive early on of local tech veterans – he said all they talked about was “doom and gloom” – and Canadian venture capitalists.

This time around, as the pandemic brought about mass economic dislocation, “anti-fragility” – the notion that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger – became Shopify’s new corporate buzzword. (Like much of what inspires Mr. Lutke, it’s drawn from his library of favourite business books – in this case, Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Antifragile.) Mr. Lutke told Shopify’s employees they were to “delete all plans,” and Mr. Miller began tapping out a blueprint to help Shopify’s customers survive the pandemic. “The concept was, ‘We have to stop everything we’re doing and understand there’s a brand-new world, where new habits will be formed and new norms will be established,’ ” Mr. Miller says. He circulated the document to staff, “and we started reorienting our roadmaps around what that could look like.”

The focus was two-fold: expanding support to existing customers, including more merchant cash advances and new banking products; and reaching out to local businesses that had never bothered to sell online and whose livelihoods were now at risk. Shopify, says Mr. Miller, had never been “overly effective at getting those digital laggards to make that transition, so a big push became, ‘How do we get all those established offline businesses online as fast as possible and get them selling?’ ”

The company quickly reorganized to push out software as quickly as it could. It introduced new features to facilitate curbside pickup and local delivery, tip collection and gift card sales. It extended its usual 14-day free trial for new merchants to 90 days and partnered with governments to help small businesses get online.

Ever the perfectionist, Mr. Lutke had always chafed at the idea of shipping “minimum viable product” and fixing the bugs later – a standard in the software industry. But “we said, ‘Let’s take our minimum quality bar for what something needs to look like for us to ship it, and just dial it down a notch or two to see what might actually be ready to ship if we do this, and if some of these things might be really valuable,’ ” the CEO says. Some hasty efforts made him cringe, including a 35-page product feature document for customers that Mr. Lutke says “actually almost killed me because it was such a visceral side of how terrible it was to sign up for a store.”

Nonetheless, Shopify managed to bring on an estimated 220,000 net new merchants in the second and third quarters, according to RBC Capital markets analyst Paul Treiber, and helped mitigate devastation for many of them, including 34-year-old Great Lakes Brewery of Toronto. Overnight, 40 per cent of Great Lakes’ business dried up as restaurants, bars and its own tap room closed down. In March, it started selling alcohol through Shopify (before that, it had only sold company merchandise online) and managed to replace most of the business it had lost because of the pandemic, selling hundreds of cases a week for delivery or curbside pickup. “We’re not as scared now as we were” 11 months ago, says Great Lakes’ Troy Burtch.

But it was a grinding year that took its toll on Shopify. Several of the key players who had contributed to Shopify’s success – including product leaders Chris Lobay, Louis Kearns, Michael Perry and Sylvia Ng, and marketing executives Bruno Roldan, Jason Naidu and Arati Sharma – left.

That exodus included Mr. Miller. He was one of Shopify’s first big outside hires in 2011, when he was brought on as chief marketing officer after leading product for eBay Inc.’s Kijiji classifieds business. He and Mr. Lutke had their differences over the years – Mr. Miller was more of a get-it-out-fast product guy than the boss – but they worked well together. “Craig has an extremely piercing intellect that cuts right through issues to their essence and always added a lot to conversations,” Mr. Lutke says.

Trust is a big thing for Shopify’s CEO. He likes to say that everyone who joins the company has a “trust battery” set at 50 per cent – and that can go up or down depending on how well they perform. The hardest trust battery to charge has been in product, where Mr. Lutke’s gaze is particularly intense. “There seems to be a direct inverse correlation between people reporting directly to Tobi on product and their longevity at Shopify,” says Matt Roberts, a Toronto-based venture capitalist who has known the company’s leaders since the 2000s.

Mr. Lutke is unapologetic. “I have no particular need to be described as ‘the friendliest boss I ever had,’ ” he says. “I want people to talk about having done the best work of their lives with me.”

Mr. Lutke shifted Mr. Miller to the product portfolio in the mid-2010s and made him CPO in 2017. “Tobi always wanted to make sure the people he worked with really care as much as he does,” says Mr. Miller. “I think I was able to earn his trust over the years.”

But as the pandemic wore on, Mr. Miller says his boss had some very strong opinions on where product should go, and the two “saw the world differently.” Mr. Miller won’t elaborate, but adds, “Effectively there can only be one chief product officer. That’s when we decided it was time for him to run it and for me to depart the company.”

They both describe the decision as mutual and amicable, though Mr. Miller calls it “one of the more difficult decisions of my life. But I also recognize that ultimately, Shopify will do incredibly well under Tobi’s leadership, so it was the right time for me.”

For his part, Mr. Lutke describes Mr. Miller as “a hugely influential, hugely important person. It was just time for a change.” His own tenure as CPO, he says, will be “temporary, but medium term.” (Incidentially, Mr. Lutke wasn’t the only tech CEO to dive back into company operations last year – Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg did the same.)

“There is no better product visionary than Tobi,” Mr. Finkelstein says. “I think he can play the role of being a world-class CEO while also running product in a way I don’t think anyone else could.”

But it does suggest product could remain a tricky department within Shopify for years to come, with a revolving slate of leaders under the watch of a hands-on and perennially dissatisfied CEO. That can be hazardous for any company.

“I don’t think you can be the type of leader that’s disruptive and not supportive of your product leadership,” says Dax Dasilva, CEO of Lightspeed POS Inc., who built the Montreal point-of-sale software provider’s original product and hired veteran tech executive Jim Texier as chief product officer in 2019. “If you don’t have confidence in them, then there’s a problem. A true leader creates leaders. You don’t create leaders to go in and meddle and undermine them.”

Another of Shopify’s pandemic-related moves could also challenge the company internally: the decision to largely abandon physical offices and make working from home permanent, even after the crisis abates. Mr. Roberts says the company had an ingrained culture of “working-togetherness” that fed off spaces that were so creatively designed they were featured in style magazines. Startups backed by Mr. Roberts’s VC firm, ScaleUP Ventures, have seen an increase in job applications from Shopify employees.

Mr. Finkelstein says Shopify is “trying to be as thoughtful about the digital-by-default dynamic and work environment as we were when we were working in offices.” That includes providing funds to employees for cameras, microphones and lighting, and increasing communications. “I don’t think we’ve got that right yet. That is one of the challenges we are certainly seeing.”

The changes of the past year are a reminder that Shopify is still a work in progress. “I think it’s hard for a company that grows really fast to always figure out what the next version of itself should look like,” Mr. Miller says. “Some of what we’d been doing up to 2020 was due for revamping, and some was the secret sauce of Shopify. It was just tricky to know which to change.”

As Mr. Lutke tinkers with Shopify’s products, the company is entering a new phase, raising questions around whether it can hold onto the hundreds of thousands of merchants it gained during the pandemic and maintain its rapid pace of growth.

The company has staked a commanding position in e-commerce, winning praise from digital-economy thinkers like Stratechery’s Ben Thompson and New York University professor Scott Galloway, who have crowned Shopify the anti-Amazon. According to The Wall Street Journal, Shopify merchants sold more goods over the U.S. Thanksgiving holiday – US$5.1-billion worth – than all of the third-party merchants on Amazon, who pay significantly higher fees (about 30 per cent of sales) and don’t have nearly as much control over their brand as they would with Shopify. It’s cheaper, too: The company charges merchants 2.9 per cent plus 30 U.S. cents per transaction it processes.

Shopify is further moving into Amazon territory with the launch last year of its first consumer-facing app, Shop, which allows users to track packages ordered from Shopify merchants, notifies them about nearby Shopify merchants and promotes featured items. Mr. Finkelstein insists Shop is not a marketplace – though the aggregation of Shopify merchants on one app points to opportunities for generating more sales and advertising revenue.

Many observers think Amazon is limited in its potential competitive responses to Shopify’s incursion. It closed Amazon Webstore, a rival e-commerce platform for small retailers, in 2015. Reviving it, says National Bank Financial analyst Richard Tse, “would be in conflict with their current business model.”

Boris Wertz, a Vancouver-based venture capitalist who has known Mr. Lutke for years, says Amazon “could care less about individual retailers and never thought about giving them the space to build their own customers. The platform is Amazon. The destination is Amazon.” With Shopify, conversely, “the brand is the retailer.” Wertz is pretty sure Amazon will eventually create a “much better product” than Amazon Webstore. “They can obviously build it,” he says. “I’m just not sure the sellers will trust Amazon in that way.”

But Amazon could still throw a trick or two at Shopify. Though the Ottawa company dwarfs its rivals, it does have a few competitors, including Texas-based BigCommerce Holdings Inc., which booked US$109.2-million in revenues in the first nine months of 2020 (it went public this past summer). Mr. Roberts says Amazon “could buy BigCommerce tomorrow without sweating,” adding, “They don’t even have to win, just make it difficult for Shopify to continue to enjoy the robust growth they have.”

Mind you, Shopify is sitting on US$6.1-billion in cash and equivalents, so it could easily make acquisitions of its own to fortify its position. In 2019, it paid $450-million for a warehouse robotics company to help provide warehousing and fulfilment support to its customers, much like Amazon does. But Mr. Lutke admits deal-making isn’t his forte. “I honestly haven’t cracked the code on M&A yet,” he says. “I have a great M&A strategy, which is, ‘Let’s be prudent about it.’” He says Shopify walks away “all the time” from potential deals.

Mr. Roberts says Shopify’s “not-built-here attitude will have to change as they need to expand into areas they don’t know particularly well. It’s better to acquire companies that have that DNA.”

Perhaps the biggest weakness Amazon could exploit is Shopify’s lack of intellectual property. Two years ago Shopify had zero patents, reflecting another of Mr. Lutke’s long-standing biases. “An idea is worth exactly one good bottle of scotch,” he says. “I think it’s a farce that patents can be granted for anything, anywhere, in the tech industry.”

It’s a stance that makes IP experts cringe. Most software giants have patent war chests; Amazon has well over 10,000 of them.

At the behest of chief legal officer Joe Frasca, Shopify has taken a more active approach, filing applications, buying patents from AT&T and suing to invalidate other companies’ IP. “Everyone has patents, so we have patents too,” Mr. Lutke says coldly. “They come in handy.”

So far, Shopify has amassed a few dozen. As it expands – particularly into warehousing and fulfilment – “they’ll need patents in that space,” says Ottawa-based patent lawyer Natalie Raffoul. “They really are playing catch-up and are vulnerable.” Should Amazon sue for infringement, she says, “It starts to become a very expensive distraction for Shopify. I love the way they want to arm the rebels, but make sure you have some armour to do so.”

Lynn-Marie Angus works on a new batch of soaps in her basement studio.Alia Youssef/The Globe and Mail

Shopify likes to promote a romantic version of entrepreneurship – as a noble career for fiercely independent people. Shopify merchants, says Mr. Finkelstein, “have adapted faster than the general average of business, which is why it’s a tale of two business worlds now through COVID-19: the resistant ones that have not adapted and have closed, and the resilient ones that, instead of grabbing their towel when they saw a tidal wave, grabbed their surfboard.”

One of the latter is Lynn-Marie Angus, owner of New Westminster, B.C.-based Sisters Sage, which makes hand-crafted soaps, smudges, salves and bath bombs using traditional ingredients. She was preparing to turn the side business into her full-time gig when the pandemic hit, shutting off access to pow-wows, conferences and craft fairs. After “crying for a week,” she says, a fellow female Indigenous entrepreneur reached out to Shopify, which contacted Ms. Angus to help move her business online. Sales have been so strong that she might never again bother with physical markets. “Shopify has shown me how I should be managing and honouring my time,” she says. “For me, it was life-changing.”

But the truth is, many of the merchants Shopify signs up each year don’t survive. The company won’t disclose its “churn rate” – the number of customers that leave the platform in a given period – but RBC’s Mr. Treiber estimates churn hit a record 400,000 in the third quarter – 100,000 fewer than the number of new stores added in the period, his research shows.

The big question now is, how many more merchants are there left for Shopify to sign up? Its growth was so strong in 2020 that analysts warn the pace this year could be much slower. Citigroup analyst Walter Pritchard says so many retailers flocked online last year that “merchant acquisition becomes tougher. If anybody had a need for e-commerce in 2020, they probably went out and found something.”

Meanwhile, Veritas Investment Research analyst Chris Silvestre estimates Shopify merchants have captured nearly half of potential sales in the United States, excluding those on Amazon and other marketplaces, plus giant online retailers that likely won’t use Shopify’s platform. The company “is now so large that sustaining the recent pace of penetration gains in the U.S. is unlikely,” he wrote in November.

This is all bound to weigh on the company’s stock. Even before the pandemic, Shopify’s shares were expensive; since last year, investors have more than doubled its valuation to about 49 times the coming year’s forecast revenues. “We believe shares of Shopify may come under pressure when the company laps its superlative [2020] sales growth,” said Tom Forte of DA Davidson in a recent research note. He thinks Shopify’s sales will only grow by 25 per cent in 2021 – which would be its weakest year of the past decade.

Mr. Lutke and his executive team know last year’s spike won’t likely be repeated. “Will the growth rate of e-commerce continue…at this pace? Probably not,” Mr. Finkelstein said in December. Future growth, he added, “got pulled forward. It’ll probably stay around where it is now.”

But the prospect of a temporary slowdown doesn’t seem to faze Mr. Lutke. “I had venture capitalists pass on Shopify 10 years ago because they didn’t think there was a market for more than tens of thousands of online stores,” he says. “E-commerce is now somewhere below 30 per cent of sales. What’s the equilibrium? I imagine it will end up around 50.”

So if there’s one thing Mr. Lutke is optimistic about, it’s that Shopify and its rebel alliance still have plenty of room to grow.

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.