Toronto last feasted on Joseph Mallord William Turner more than 11 years ago with the superb Turner, Whistler, Monet exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario. It was a huge success critically and commercially, drawing more than 210,000 visitors (thereby making it the AGO’s seventh best-attended show) before travelling to the Galeries nationales du Grand Palais in Paris and Tate Britain in London.

Turner makes a triumphant return to the AGO this weekend, in a (largely) solo showcase titled J.M.W. Turner: Painting Set Free. The exhibition features 65-plus oil paintings, watercolours and etchings by the British master (1775-1851), most drawn from the permanent collection of Tate Britain, the single largest repository of the artist’s work in the world. The AGO show, in fact, originates with the Tate, which last fall mounted some 160 Turners, then allowed smaller, more distilled versions thereof to be displayed, first at the Getty in Los Angeles and, most recently, at San Francisco’s de Young.

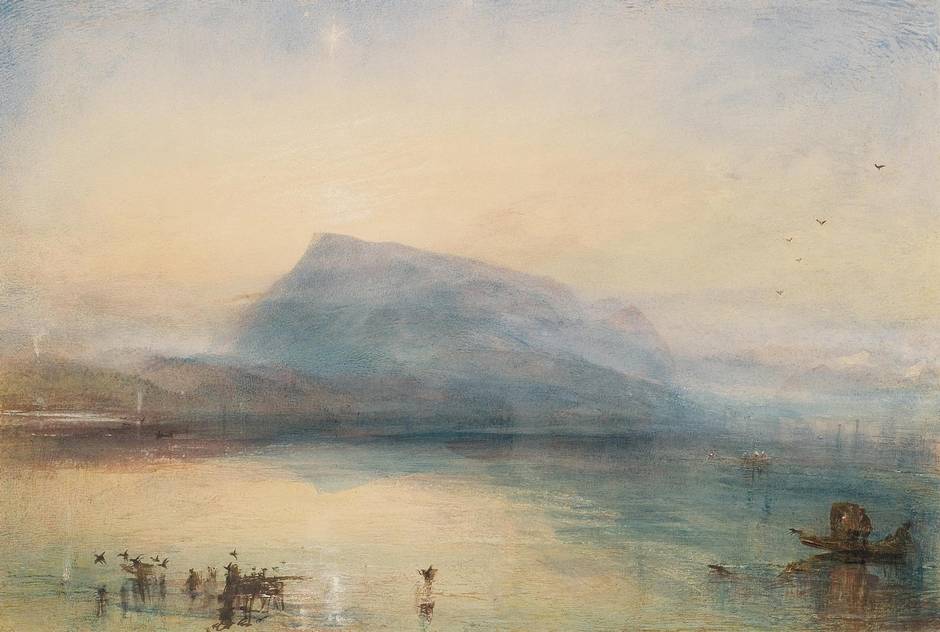

As elsewhere, the focus at the AGO is on Turner’s output in the last 15 of his 76 years. Today much of the work from that period – including oils such as Rain, Steam and Speed (1844), Snow Storm (1842) and Sunrise, with a Boat between Headlands (1845) and the watercolours The Blue Rigi (1842) and Bamburgh Castle (1837) – is regarded as quintessential Turner, the best in a brilliant career, a harbinger of sorts, in fact, of what Whistler, Monet, Gustave Moreau, Mark Rothko, Helen Frankenthaler, James Turrell and Cy Twombly, among others, got up to.

But in Turner’s day, it was the earlier works that were deemed his most accomplished. The so-called late paintings were seen as “a steep falling away,” disparaged for their indistinct forms, too-adventurous colour schemes, opaque subjects, vaporous atmospherics, “perplexing personal symbolism,” among other crimes against art. So seemingly radical were these works that none other than critic John Ruskin, previously his most ardent champion, suggested they were “indicative of mental disease.” Others blamed Turner’s fondness for sherry, bad gums, poor diet, cataracts, even the failure on his part to cultivate “the society of pure educated women.”

None of this guff comes to mind while wandering the spacious temporary galleries on the AGO’s second floor, Turner’s “home” for the next three months. Instead, what strikes the viewer is luminosity, colour, energy, bravura painterliness … genius. Better than textbook reproductions, these real things demonstrate how Turner pushed the application of pigment to a flat surface beyond its traditional functions as a vehicle to deliver narrative and a mimetic, illusionistic representation of the “real” world into realms where paint is a communicative medium unto itself.

When the Tate first considered an exhibition of late Turners, it was in large part with the intention of “re-examining or rebalancing the idea of Turner as a proto-Modernist, a kind of Rothko before his time,” noted David Blayney Brown, Tate curator of British art, 1790-1850, during a recent visit to Toronto. Not having seen the original Tate show, I can’t say how palpable that agenda felt to viewers there, but in Toronto it’s carried rather lightly. Indeed, there is no lack of opportunity to compare the Turner oeuvre with work by predecessors, contemporaries and antecedents, all of it drawn from the AGO’s own holdings.

Perhaps the most audacious (but nonetheless apt) juxtaposition occurs in the section titled Past and Present, in which the AGO’s curator of European art, Lloyd DeWitt, has positioned two 1843 Turners, The Morning After the Deluge and The Evening of the Deluge, adjacent to a pair of oils by Toronto artist Stephen Andrews, 59.

T.S. Eliot once observed that the art of the present is directed by the past as much as our perception of the past is altered by great works of contemporary art. With respect to Turner, this notion could be construed as a kind of “retrospective determinism” – that somehow (but inevitably) Impressionism, say, and Colour Field painting were contained in Turner’s canvases, such that in 1966 Rothko could joke: “This man Turner, he learned a lot from me.”

The great thing about Painting Set Free, which is organized by theme rather than chronology, is that it presents Turner as very much his own man (and a very manly one at that), requiring no buttressing from past and present sources. His “cause,” of course, is helped by the mostly high quality of work at the AGO. Admittedly, it would have been wonderful had the exhibition included the epochal The Fighting Temeraire (1839) and Rain, Steam and Speed (1844), but both are held by the National Gallery in London and, in the case of Rain, Steam and Speed, which was included in the Tate show last year, it’s too fragile to travel. Nevertheless, Toronto is hosting several bona-fide classics, including the astonishing square canvas Peace – Burial at Sea (1842) and the downright “intangible and mysterious” Sunrise with Sea Monsters (1845), plus the previously mentioned Snow Storm (for which the AGO is running a scene from the 2014 feature film Mr. Turner, depicting the likely apocryphal episode that prompted the painting’s creation; it is, in fact, on one of three screens the AGO is using for excerpts from Mr. Turner) and The Blue Rigi. The last, surely one of the world’s greatest watercolours, is a sunrise picture so subtle, so perfect, the paint seems to have been not so much brushed onto the paper as whispered.

Similarly marvellous is Venice: Santa Maria della Salute, Night Scene with Rockets, from 1840. Clearly an inspiration for the Whistler Nocturnes that would come 30-plus years later, it’s a watercolour and gouache on paper with the presence of an oil and pastel on canvas. Observed Blayney Brown: “By the end of Turner’s life he was starting to use oil as if it was watercolour – in other words, thinly – and the paradox is that as a young man, he was trying to make watercolour look like oil!”

J.M.W. Turner: Painting Set Free is at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, through Jan. 31 (ago.net).

Editor's note: The original version of this article stated that two paintings by Toronto artist Stephen Andrews, After Before and After After, are in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario. They are, in fact, in the collection of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery in Owen Sound, Ont. This version has been corrected.