Richard Nixon in 1970; Donald Trump in 2020.Mike Lien/The New York Times; Evan Vucci/The Associated Press

Early one February morning in 1807, on a rural road in southern Alabama, an army officer arrested Aaron Burr. The former vice-president was accused of an outlandish plot. It was alleged that he had assembled a force of armed men with the goal of seizing land in the southwestern U.S. and from the Spanish empire to found a new country under his rule. He was taken to a federal court in Richmond, Va., to face charges of treason. His sensational trial would captivate the young republic.

Half a century later, there was a halting attempt to prosecute the leader of the Confederacy after the Civil War. One U.S. president faced the serious prospect of criminal charges. Another, meanwhile, was once arrested for street racing.

But as Donald Trump’s hush-money trial opens in New York on Monday, it marks the first criminal prosecution of a former U.S. president. And it likely will not be the last: He is also under other indictments – two for attempting to overturn the 2020 election, and one for stashing classified documents at his Florida estate.

The precedents to his legal cases offer some idea of what to expect as Mr. Trump stands in the dock. They also, however, help reinforce how utterly singular his case is.

A 1792 portrait of Aaron Burr by artist Gilbert Stuart hangs in the New Jersey Historical Society museum in Newark, N.J., July 2004.The Associated Press

Not standing still but lying in wait: Aaron Burr

When Mr. Burr’s vice-presidency ended in 1805, he headed west. In his travels through the recently acquired Louisiana Purchase, he raised money and recruited people for a new project. On an island in the Ohio River belonging to Harman Blennerhassett, a wealthy landowner, Mr. Burr assembled men and supplies.

Exactly what Mr. Burr’s project was would later be disputed. He would claim that he was simply putting together an expedition to settle land in Texas, a Spanish possession at the time. People whose help he had sought, including British and Spanish diplomats, said he had told them about a far more sweeping plan to carve out a new nation. In some versions of the story, Mr. Burr even planned to invade the entirety of the U.S. or Mexico and set up his own empire.

Ultimately, Ohio’s Governor sent militia to raid Blennerhassett Island. General James Wilkinson, one of Mr. Burr’s erstwhile co-conspirators, informed President Thomas Jefferson of the plot. And Mr. Burr made a final flight into the wilderness that ended on that Alabama road.

His months-long trial, presided over by Chief Justice John Marshall, turned in large part on a letter Mr. Burr had written in cipher to Gen. Wilkinson, which appeared to confirm some of the plan’s details. It turned out, however, that Gen. Wilkinson had altered the letter in a bid to minimize his own role in the conspiracy.

Also at issue was the legal question of what specifically constituted treason. Justice Marshall instructed the jury to stick to the narrow wording of the U.S. Constitution, which defined the crime as an act of war against the U.S. or helping the country’s enemies.

Since Mr. Burr had never actually launched an attack, he was acquitted.

To R. Kent Newmyer, author of The Treason Trial of Aaron Burr, the main similarity between that case and Mr. Trump’s is the country’s riveted attention. “Burr’s trial was a national media event,” he said. “The whole atmosphere in Richmond was electric.”

The personalities involved, however, make them very dissimilar. While Mr. Burr, like Mr. Trump, was “insanely ambitious,” Prof. Newmyer said, he was otherwise a contrasting figure – a skilled lawyer and a war veteran lauded for bravery during the American Revolution. And unlike Mr. Trump’s ever-rotating legal team, Mr. Burr was represented by Luther Martin and Edmund Randolph, brilliant defenders who had served in the Constitutional Convention. “It’s what Karl Marx said: History repeats itself, the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce,” Prof. Newmyer said.

James Lewis, a historian at Michigan’s Kalamazoo College, cites the stark partisan divide over Mr. Burr’s trial as perhaps the one similarity with Mr. Trump’s. Mr. Jefferson’s supporters were convinced that Mr. Burr was guilty of plotting against the nation. The opposition Federalists, meanwhile, preferred his acquittal because they viewed the prosecution as a vendetta by Mr. Jefferson, who had never forgiven Mr. Burr for running against him in 1800.

“There was this really clear political divide over who thought the trial should happen at all,” said Prof. Lewis, author of The Burr Conspiracy.

The comparisons with Mr. Trump’s case, however, end there. There was the unresolved factual dispute over Mr. Burr’s intentions. Mr. Jefferson’s direct involvement in the case, meanwhile, was unlike today’s prosecutorial structure: during Mr. Burr’s trial, the President directed the government’s lawyers and authorized blanket pardons for co-conspirators willing to help secure a conviction.

Also, Mr. Burr was a spent political force by the time of his trial. Two years earlier, he killed former treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton in a duel. While he was never tried over it, there was no real prospect of him running again for president, much less assailing the justice system for electoral gain.

“I’m more struck by the differences than by the similarities,” Prof. Lewis said. “He was not attacking justices. He didn’t have followers to raise threats about what would happen if the court dared to find him guilty.”

Most notably, Mr. Trump is not charged with treason, an offence whose very specific definition may be the Burr trial’s most lasting legacy.

A statue of Jefferson Davis in front of the Alabama State Capitol Building, in April 2018.ROBERT RAUSCH/The New York Times News Service

Confederate kingpin: Jefferson Davis

Unlike in Mr. Burr’s case, there was no real question regarding what Jefferson Davis had done, at least on a big-picture level: as president of the Confederacy, he had spent four years leading a rebellion against the U.S. government. Much as with Mr. Trump in his election-related indictments, Mr. Davis’s defence was expected to rely primarily on arguments that his actions had not constituted a crime.

Captured in May, 1865, at the end of the Civil War, Mr. Davis was jailed at a Virginia military base while the U.S. government debated what to do. Initially, there was talk of having him tried before a court-martial for the assassination of Abraham Lincoln or Confederate massacres of Union prisoners. But investigations failed to turn up evidence directly connecting him to either. President Andrew Johnson opted for a treason trial in a civilian court. Like Mr. Burr, Mr. Davis faced hanging if convicted.

Mr. Davis was set to argue that, during the war, he had been the leader of a foreign country and not a U.S. citizen, therefore attacking the U.S. could not be considered treason. Such a defence posed a problem for Mr. Johnson: if successful, it would establish that the Confederacy’s secession from the Union had been legal – a dangerous precedent for national unity.

“Johnson was very wary about what would happen if it went to trial and didn’t lead to a conviction,” said Jonathan White, a Civil War expert at Christopher Newport University.

Two other complications were the judges involved. One, John Underwood, told the Senate that he could pack a jury to secure a conviction – an assertion that made the proceedings sound like a kangaroo court. The other, Chief Justice Salmon Chase, did everything he could to thwart the prosecution, given his own presidential ambitions and desire not to alienate southern voters. He failed to show up for hearings and came up with various reasons to delay the proceedings.

Then Justice Chase advised Mr. Davis’s lawyers to argue that, because the recently passed 14th Amendment to the Constitution barred former Confederates from holding elective office again, Mr. Davis had now been punished and should not be prosecuted further. When they moved to dismiss the case on this basis, Justice Chase voted to grant the motion. Judge Underwood voted against. The matter would have to be resolved by the Supreme Court.

Before that happened, Mr. Johnson intervened. On Christmas Day, 1868, he issued a general amnesty for former Confederates. Two months later, prosecutors at the Davis trial formally dropped the charges.

“Throughout his presidency, Johnson had been lenient toward ex-Confederates. This was his last act in that progression,” Prof. White said.

The questions over judicial impartiality may have a parallel in one of Mr. Trump’s cases. Florida judge Aileen Cannon, overseeing the classified documents proceedings, has written proposed jury instructions that would effectively direct jurors to accept one of Mr. Trump’s major legal arguments.

The delays in Mr. Davis’s case have also found analogues in Mr. Trump’s election and hush-money prosecutions. His efforts to overturn the election unfolded, often in plain sight, in late 2020 and early 2021, but it took nearly two years for Attorney-General Merrick Garland to appoint a special counsel to decide whether to charge him. The hush-money details, meanwhile, have been public knowledge since 2018, but it took five years for prosecutors to indict Mr. Trump.

And the former president has himself repeatedly tried to delay all of his legal proceedings until after November’s election.

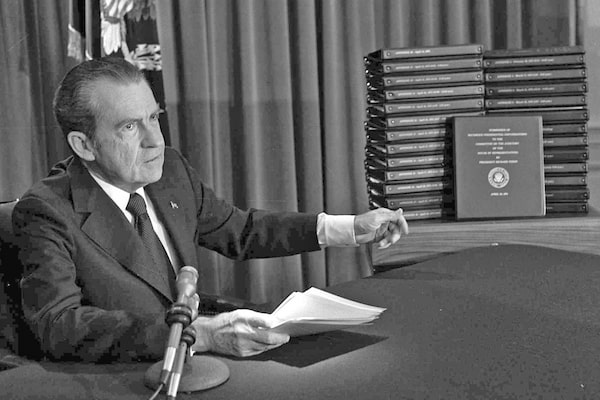

Former U.S. President Richard Nixon announces during a nationally-televised speech that he would turn over the transcripts of the White House tapes to House impeachment investigators, in Washington on April 29, 1974.The Associated Press

Scandalous POTUS: Richard Nixon

During his time in the White House, Richard Nixon oversaw a program of dirty tricks and surveillance targeting everyone from political opponents to his own staff. When his operatives were caught burgling Democratic Party headquarters in the Watergate complex, he used his presidential power to try to cover it up. In the famous “smoking gun” tape, he was recorded scheming to use the CIA to stop an FBI investigation into the break-in.

Forty-eight people were convicted in relation to the Watergate scandal, including Mr. Nixon’s attorney-general, chief of staff and several other government officials. Under the threat of impeachment, Tricky Dick resigned.

In an unrelated case, Mr. Nixon’s original vice-president, Spiro Agnew, shared with Mr. Burr the dubious distinction of being one of only two holders of the country’s second-highest office charged with a crime. Mr. Agnew resigned in 1973 after pleading guilty to tax evasion in relation to a bribery scandal.

The analogues between Watergate and Mr. Trump’s cases are not hard to see: accusations of abuse of power and questions around indicting a former president.

“Watergate was an attack on democracy. It was a burglary of the opposition party’s headquarters to subvert an election,” said David Greenberg, a Rutgers University history professor and author of the book Nixon’s Shadow. “It’s in the same family as what Trump did after the 2020 election.”

Mr. Nixon, like Mr. Trump, tried to claim that he legally did not have to turn over key documents. And Mr. Nixon’s famous formulation that “when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal” is the exact argument Mr. Trump is making before the Supreme Court in a bid to get his indictments thrown out.

“Nixon’s defence hinged on claims of presidential immunity. He kept invoking executive privilege,” Prof. Greenberg said. “With Trump, you see all of these same themes.”

The key difference, of course, is that Mr. Nixon ultimately was never indicted; his successor, Gerald Ford, pardoned him shortly after taking office. The reaction to his deeds was also far less partisan. By the time he resigned, even Mr. Nixon’s own party was pushing him to go gently into that good night.

Mr. Trump, by contrast, has locked down this year’s Republican presidential nomination and could soon be returning to the White House.

“It’s rather amazing and rather scandalous that we have no safeguard against someone who is going to trial or even is convicted of serious crimes running for and being elected to office,” Prof. Greenberg said. “We assume the American people are not going to elect a criminal, which is no longer a reliable bet.”

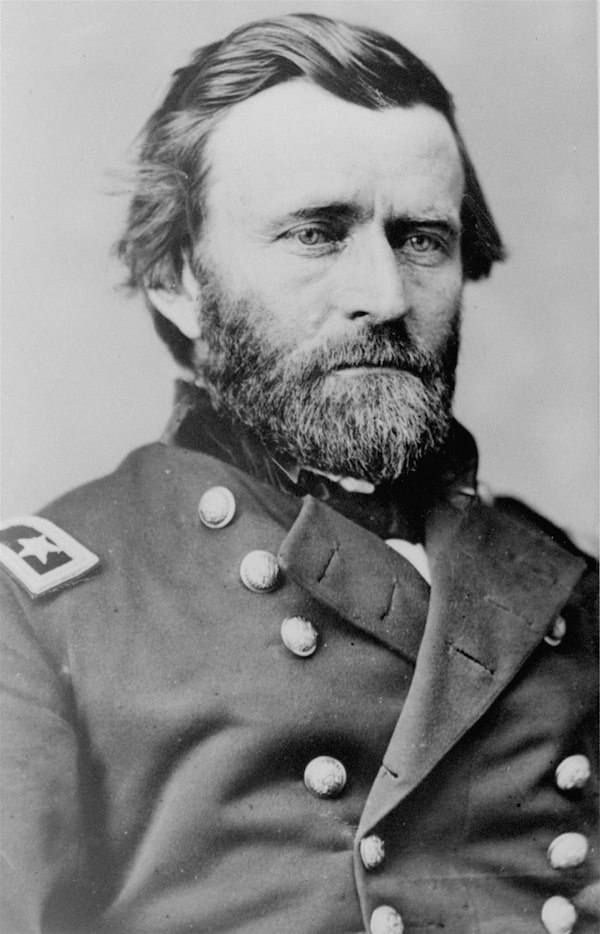

A portrait of former U.S. President Ulysses Grant.MATHEW B. BRADY/AP

Fast but not furious: Ulysses Grant

Ironically, the only presidential arrest to precede Mr. Trump’s is about as different a case as it is possible to imagine. For one, the infraction was a civil traffic offence. For another, the chief executive involved reportedly made no attempt to contest the proceedings.

While Mr. Trump argues that presidents should be fully immune from prosecution for anything they do while in office, the brief detention of Ulysses Grant reads as a parable about his acceptance that no one is above the law.

The episode took place one evening in 1872, when police officer William West pulled over a group of drivers racing horses and buggies down 13th Street in Washington, D.C. The leading carriage was piloted by Mr. Grant, then in his first term as president.

“Do you think, officer, that I was violating the speed laws?” a smirking Mr. Grant said, according to an interview Const. West later gave to the Sunday Star newspaper. The officer had stopped the President the previous day and cautioned him over his driving. So this time, Const. West took Mr. Grant to the police station.

According to the officer’s account, Mr. Grant’s friends – some of whom were “prominent officials” – bitterly disputed their arrests. But the President himself paid his fine without complaint and walked home.

Const. West, a Black veteran of the Civil War who had once served under Mr. Grant’s command, said the President subsequently contacted the police chief to ensure Const. West would not face repercussions for his executive traffic stop. The two even subsequently became friendly. When Const. West and Mr. Grant would run into each other around town, they would stop to talk, bonding over their mutual interest in fast horses.

Editor’s note: Because of an editing error, a previous version of this article incorrectly stated the number of indictments Donald Trump is facing. This version has been updated.