Retired nurse Patty Peek, 70, lives on the north side of the Straits of Mackinac, just a few hundred metres from where Enbridge's Line 5 pipeline runs under the water. She runs a residents' group that wants it shut down.Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

Bonus podcast • Adrian Morrow discusses Line 5 on The Decibel

Patty Peek’s front yard sits on the intersection of the environment and the economy.

From her veranda overlooking the Straits of Mackinac, where Lakes Huron and Michigan meet, the 70-year-old retired nurse practitioner surveys the aquamarine waters shimmering under a golden Thursday afternoon sun. Forests of pine and birch hug the banks.

Freighters carrying iron ore and grain pass ferries full of tourists bound for Mackinac Island, a Michigan state park with a historic fort. The ships are buffeted by the notoriously strong currents of this six-kilometre-wide passage between the state’s Lower and Upper Peninsulas.

But the most tumultuous waves these days are coming from something not visible on the surface.

A few hundred metres from Ms. Peek’s waterfront home, the Line 5 pipeline stretches across the bottom of the Straits. Through it flows more than 85 million litres of crude oil and natural gas every day.

She worries about it rupturing. Such a disaster would poison drinking water, end the tourist trade, kill off the local fishery and bring ship traffic to a halt.

“If there is a spill, this area will be dead,” Ms. Peek says. “It would be devastating.”

This rural idyll is currently the hottest front in North America’s pipeline wars, and the latest binational friction point in Canada-U.S. trade. Owned by Edmonton-based Enbridge Inc., 68-year-old Line 5 is part of a network connecting Alberta’s oil sands with refineries in Ontario and Quebec.

Over the past decade, it has generated mounting opposition in Michigan. In May, Governor Gretchen Whitmer ordered the line shut down. Enbridge refused, and the two sides are now in court-ordered mediation.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, meanwhile, is lobbying U.S. President Joe Biden, demanding he intervene to protect the pipeline. Ottawa has signalled it might invoke an obscure 1977 treaty to keep the line open.

Enbridge warns of dire economic disruption if Line 5 closes, including gasoline shortages in Canada’s two most populous provinces. The company insists the pipeline is perfectly safe. “We hear lines like ‘ticking time bomb,’ and that’s so far removed from the science and the engineering,” says Mike Fernandez, Enbridge’s chief communications officer. “This is not a pipe that’s about to fail.”

But many Michiganders do not trust Enbridge’s assurances. Another of the company’s pipelines in the state, Line 6B, ruptured in 2010, dumping more than three million litres of oil sands bitumen into the Kalamazoo River. And repeated damage to Line 5, including a pummelling by a tugboat anchor in 2018, have heightened fears of a spill.

Much of the fury here is specific to Line 5′s unusual circumstances. The pipe sits in open water under a key shipping lane, amid a picturesque holiday destination. But it also carries wide-ranging implications for the future of oil and gas infrastructure on the continent.

Unlike previous pipeline battles, which concerned unbuilt project proposals, this is the first serious attempt to shutter a line already in service. Environmentalists see it as a major salvo in the fight against global warming, whose deadly consequences – from wildfires to record-breaking heat waves to torrential floods – have been inescapable around the world this summer.

“If oil pipelines are ever going to be shut down, which climate change suggests they will, Line 5 should be the first. It’s in the middle of the Great Lakes, 20 per cent of the world’s fresh water,” says Jim Lively, program director of The Groundwork Center, a Michigan social justice organization campaigning against the line. “This is the dumbest pipeline ever built.”

At a glance, the streets of Mackinac Island could be mistaken for many of Canada's historic tourist towns like Niagara-on-the-Lake or Lunenburg, N.S. It's also home to Fort Mackinac (bottom left), a historic stronghold that British and Indigenous forces captured during the war of 1812, and the Michigan governor's summer residence (bottom right).Photos: Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

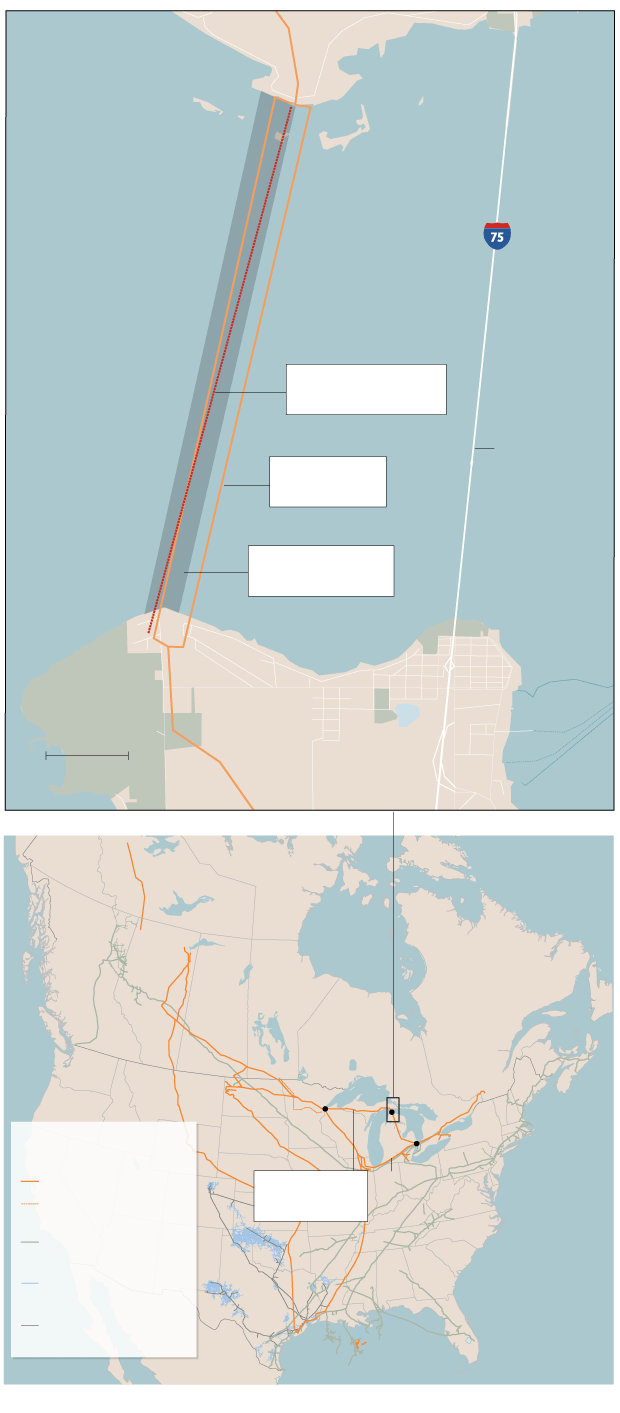

DETAIL

Straits of Mackinac

Proposed pipeline

replacement segment

Mackinac

Bridge

Existing Line 5

dual pipelines

Pipeline and tunnel

easements

Mackinaw City

0

900

METRES

MICHIGAN

CANADA

Mackinaw

City

Superior

Enbridge’s energy

infrastructure

Sarnia

U.S.

Liquids pipeline

Enbridge Line 5

pipeline

Line 78

Liquids pipeline

(proposed)

Natural gas

transmission pipeline

Natural gas gathering

pipeline

Natural gas liquids

pipeline

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ENBRIDGE;

government of michigan

DETAIL

Straits of Mackinac

Proposed pipeline

replacement segment

Mackinac

Bridge

Existing Line 5

dual pipelines

Pipeline and tunnel

easements

Mackinaw City

0

900

METRES

MICHIGAN

CANADA

Mackinaw

City

Superior

Enbridge’s energy

infrastructure

Sarnia

U.S.

Liquids pipeline

Enbridge Line 5

pipeline

Line 78

Liquids pipeline

(proposed)

Natural gas

transmission pipeline

Natural gas gathering

pipeline

Natural gas liquids

pipeline

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ENBRIDGE;

government of michigan

DETAIL

Straits of Mackinac

Proposed pipeline

replacement segment

Mackinac

Bridge

Existing Line 5

dual pipelines

Pipeline and tunnel

easements

Mackinaw City

0

900

METRES

MICHIGAN

CANADA

Mackinaw

City

Superior

Enbridge’s energy

infrastructure

Sarnia

UNITED STATES

Liquids pipeline

Line 78

Enbridge Line 5

pipeline

Liquids pipeline

(proposed)

Natural gas

transmission pipeline

Natural gas gathering

pipeline

Natural gas liquids

pipeline

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ENBRIDGE; government of michigan

Line 5 was constructed in 1953, linking oil terminals in Superior, Wis., and Sarnia, Ont., via Michigan. It is a central piece of Enbridge’s web of pipelines, which stretches from northern Alberta to Montreal.

The line pumps synthetic crude from the oil sands, along with light crude and natural gas liquids. Most of it is destined for refineries in Ontario and Quebec, which produce gasoline, diesel and plastics. A smaller portion remains in the U.S., feeding refineries in Michigan and Ohio, and supplying propane for home heating in the largely rural Upper Peninsula.

In the Straits of Mackinac, Line 5 splits into two pipes, their walls double the thickness of the rest of the line. They are coated in enamel, meant to guard against rust. In places where violent water currents have eroded the bottom of the lake from under the line, support anchors hold the pipe.

When Enbridge’s predecessor company built Line 5, it obtained an easement from the state of Michigan to put the line on the bottom of the Straits. Over the years, many Michiganders appear to have forgotten about the pipeline’s existence.

It was only after the 2010 Kalamazoo spill that Line 5 came in for scrutiny. After that catastrophe, Beth Wallace, a staffer at the Michigan office of the National Wildlife Federation, wrote a report about Line 5, titled Sunken Hazard. Released in 2012, it landed like a bomb. This was the first time most environmental groups and Straits residents had heard of the line.

“I’m a native Michigander, and I had no idea there was an oil pipeline in the Great Lakes,” Mr. Lively says. “When I saw that report, I said, ‘I can’t believe this is real.’ ”

Fresh nuts, bolts and fittings are prepared to be added in 2017 to the east leg of the Line 5 pipeline near St. Ignace, Mich.Dale G Young/Detroit News via AP

Mr. Lively’s group helped organize the first protest against Line 5, at the foot of the Mackinac Bridge in 2013. Other environmental groups joined in, coalescing into an umbrella organization called Oil and Water Don’t Mix. Ms. Peek and her neighbours formed the Straits of Mackinac Alliance.

Indigenous communities also rose up. Under an 1836 treaty that ceded territory in northern Michigan to the U.S., Chippewa and Ottawa people retained the right to fish and hunt in the area. They argue the threat of an oil spill violates that right.

Whitney Gravelle, president of the Bay Mills Indian Community, says more than half the households in her tribe depend on the local fishery for their livelihood, fishing either commercially or for subsistence. The community’s creation story holds that the world began at the Straits, making them spiritually important, the frequent site of water rituals.

“It’s like our Garden of Eden. We have teachings that say as long as the whitefish continue to thrive in the Great Lakes, so will our people,” Ms. Gravelle says. “It’s the centre of thousands of years of history and travel and communication and ceremony.”

Lisa Powers, chairwoman of the Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians, recalls how her grandfather and uncles used to hunt on Mackinac Island, until population growth made it unfeasible. The pipeline, she says, is another unwanted encroachment on her community’s way of life. “They trespass,” she says. “They never asked, they just took.”

Lisa Powers and Richard Lewis are the chairwoman and elder advisor, respectively, of the Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians.Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

Even self-described conservatives in the business community joined the opposition.

Chris Shepler, whose family has run a ferry service to Mackinac Island since 1945, votes Republican and has no problem with most oil pipelines. He fears, however, that Line 5 is too great a risk. Given the region’s harsh winters and rough waters, if there is a spill, he doubts anyone could clean it up fast enough to avoid serious damage.

“I’m pro-business. I’m pro-jobs. I don’t want to tell another business what to do. But I wake up every morning thinking about the pipeline. If that thing goes, so does this company, as well as all these other companies along the lakes,” Mr. Shepler, 59, says in his office overlooking the ferry dock in Mackinaw City, on the south side of the Straits. “We all want lower oil prices – but at what cost?”

Chris Shelper, whose family runs a ferry service to the island, says he feels Line 5 is too big a risk to the area.Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

Craft beer magnate Larry Bell set up the Great Lakes Business Network to bring together private-sector leaders fighting Line 5. A break in the line would pollute water from Lake Michigan he needs to run one of his breweries. “Michigan takes an incredible amount of risk for no reward,” he says.

A series of concerning episodes and revelations, meanwhile, further hurt the pipeline’s case.

On April 1, 2018, the Clyde Van Enkevort tugboat dragged a six-tonne anchor through the Straits, denting both Line 5 pipes. In 2019, a cable from a different boat – likely one of Enbridge’s own maintenance contractors – damaged one of the support anchors securing Line 5 to the bottom of the lake. Last month, another anchor somehow became detached from a company boat and ended up sitting on the lakebed between the pipes.

Enbridge’s records also showed hundreds of cases in which it failed to ensure the pipeline was supported by either the lakebed or an anchor at least every 23 metres (75 feet), a condition of the 1953 easement. What’s more, inspectors discovered bends in the pipeline, potentially putting it under greater stress. In places, the protective coating had worn off, exposing metal to possible corrosion.

By combing through federal records, the National Wildlife Foundation discovered that other portions of Line 5 outside the Straits had leaked 29 times since the late 1960s, spilling a total of more than four million litres of oil.

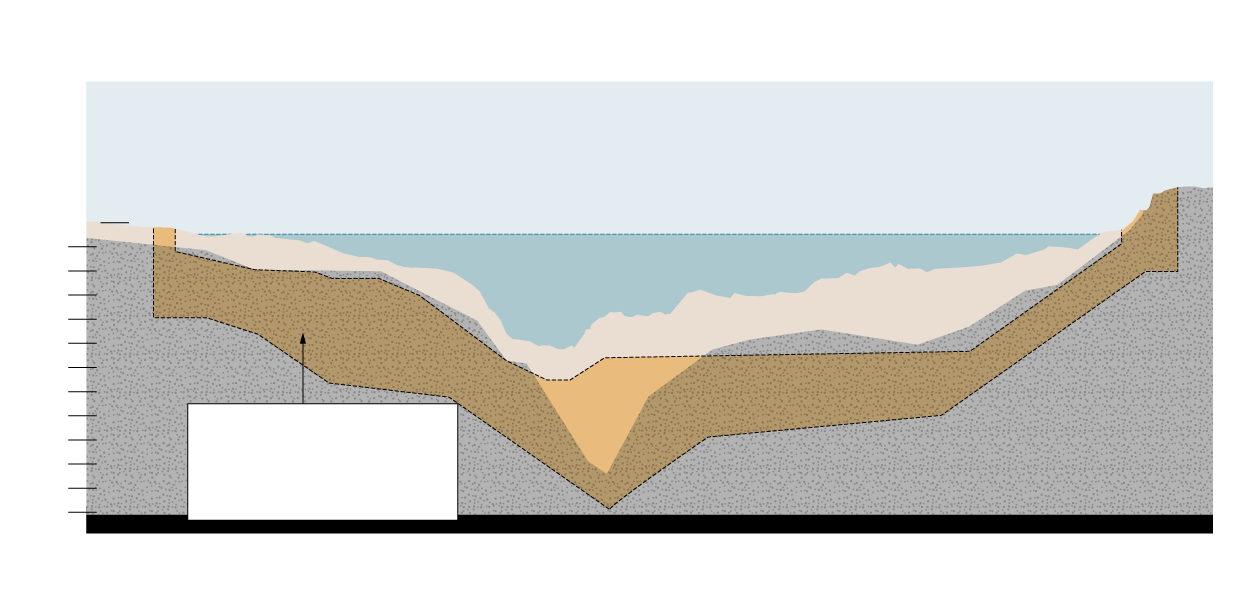

After years of protests and political pressure, Enbridge reached a deal with former Michigan governor Rick Snyder in 2018 to build a tunnel under the Straits and reroute the pipeline through it. It’s uncertain, however, how long it would take to complete the project. In the interim, the company would keep operating the current pipeline indefinitely.

Profile view of proposed tunnel

Ordinary high water mark: 580.5 feet

600 ft.

500

Lake

Lake bed

400

300

200

Rock

Tunnel will be

constructed within

these limits

100

0

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ENBRIDGE;

government of michigan

Profile view of proposed tunnel

Ordinary high water mark: 580.5 feet

600 ft.

500

Lake

Lake bed

400

300

200

Rock

Tunnel will be

constructed within

these limits

100

0

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ENBRIDGE;

government of michigan

Profile view of proposed tunnel

Ordinary high water mark: 580.5 feet

600 ft.

500

Lake

Lake bed

400

300

200

Rock

Tunnel will be

constructed within

these limits

100

0

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ENBRIDGE; government of michigan

Some critics also argue that it’s a bad idea to build such a large piece of oil infrastructure when the country urgently needs to transition to clean energy.

“We can’t keep relying on fossil fuels,” Ms. Gravelle says. “We want to make sure Enbridge doesn’t create a stranded asset that is slowly becoming a thing of the past.”

When Ms. Whitmer campaigned to succeed Mr. Snyder, she promised to shut down Line 5.

An establishment Democrat with two decades of experience in state politics, the governor is hardly a leftist firebrand. That even she would try to stop Line 5 indicates how mainstream the opposition has become.

Much of the reason is the connection the state’s citizens feel to the Straits of Mackinac, and the waters more generally. Only a few thousand people live around the Straits, but more than a million visit annually, to swim, hike and boat.

Mackinac Island is a particularly large draw. The setting for two War of 1812 battles, it offers historical sites, trails and a 19th-century village lined with bed-and-breakfasts and fudge shops. Cars are banned, and people get around by bicycle or horse-drawn carriage.

The state as a whole is surrounded by three lakes and dotted with ports. The lead poisoning crisis in Flint, which started in 2014, has also kept water on the political agenda.

“You never really had difficulty explaining to people that there shouldn’t be an oil pipeline in the Straits of Mackinac,” says David Holtz, an organizer for Oil and Water Don’t Mix. “There’s a spiritual connection to the Great Lakes here.”

Chris Rickard and Pat Beckman take a boat contracted by Enbridge to check on the pass through the Straits of Mackinac.Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

One bright, windy midday, Pat Beckman pilots a 25-foot former Coast Guard response boat past Mackinac Island toward the Dirk Van Enkevort, a tugboat pushing a barge, the Michigan Trader. His co-captain, Chris Rickard, hails the tug by radio.

“This is Enbridge boat 25540 conducting safety patrols in the Straits of Mackinac. We’d like to approach you on your port side, passing behind your stern, and coming up your starboard side,” Mr. Rickard says.

“That’ll be okay,” comes the reply.

“Can you also confirm to us that your anchors are secure?” Mr. Rickard asks.

“Anchors are secure,” says the captain of the tug, which belongs to the same company responsible for the 2018 anchor strike on Line 5.

As their craft bounces over 1.5 metre waves, Mr. Rickard photographs the Michigan Trader’s anchors using his mobile phone.

Mr. Rickard texts his photographs to Andrew Beckett, who is running Enbridge’s Maritime Operations Center in Mackinaw City.

At the centre, Mr. Beckman tracks dozens of boats approaching the Straits on a bank of computer screens. The large vessels, he dispatches Mr. Beckman and Mr. Rickard to inspect. Another Enbridge boat sits directly over the pipelines, ready to check smaller crafts.

The company set up this system in 2019, after the previous year’s anchor damage. It operates 24/7 out of a ground-floor space about the size of a school classroom, in a wooden building between a tourist restaurant and a candy store. A second command centre monitors ship traffic via cameras along the shoreline.

“We are not aware of anything like this existing elsewhere in the world,” says Bob Lehto, Enbridge’s operations manager for northern Michigan.

A slim 37-year-old with a shaved head, Mr. Lehto was born and raised on the Upper Peninsula, where he still lives. He’s a member of the Sault Sainte Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians. And he spends a lot of time on the lakes. Last weekend, he says, he took his children, aged 4 and 8, swimming in Lake Superior.

“I paddle, swim, fish. I grew up on these waters. Nobody is more concerned, or cares more, about what happens here than I do,” he says. “I’ve got a personal, vested interest.”

Workers clean up the Kalamazoo River in Marshall, Mich., in 2010.Kevin Van Paassen/The Globe and Mail

As part of a 2016 court settlement with the U.S. government after the Kalamazoo spill, Enbridge has also taken action to close gaps between support anchors on Line 5, patch holes in the pipe’s coating and run inspections to look for cracks.

Mr. Fernandez insists Enbridge learned the lessons of Kalamazoo, which the company spent US$1.2-billion to clean up. Employees are given rings made from pieces of Line 6B as a reminder that such a failure must never happen again. He also maintains that, despite the anchor hits and harsh waters, Line 5 is not at risk of breaking open.

“There has never been any damage or any true threat to the pipe itself,” he says. “The political hyperbole has moved people from understanding science and engineering, to only understanding emotion.”

Enbridge paints a picture of serious economic pain on both sides of the border without Line 5: shortages of gasoline in Ontario and Quebec, propane in Michigan, and jet fuel for the Detroit airport; energy price spikes; convoys of tanker trucks trying to make up for lost pipeline capacity.

U.S. President Joe Biden delivers a July 4 speech at the White House.Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters

The company and the Canadian government have pressed the White House to try to prevent Michigan from shutting down the pipeline.

So far, there are no signs the Biden administration will step in on Enbridge’s side. Opposition to oil pipelines is mounting within the Democratic base, and pushed the President to cancel Keystone XL’s construction permit on his first day in office. In June, in a Maine court case over a different pipeline, the federal government filed a legal brief backing the right of a local council to stop the proposed project.

In Michigan, it is unclear how the legal process will play out. The state and the company are suing each other, and currently meeting with a mediator. They plan to finish mediation this month, but have not said whether they anticipate actually resolving the dispute, or only agreeing on smaller matters, such as whether the lawsuits should proceed in federal or state court.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is also undertaking an extensive environmental review of Enbridge’s proposed tunnel, adding another potential roadblock.

Mr. Trudeau is considering invoking the Transit Pipelines agreement, a 1977 bilateral treaty that guarantees each country will allow the other’s pipelines on its territory. Under the deal, the matter could be referred to binding arbitration.

Line 5′s opponents reject the framing of the issue as a clash between two countries. They point to pipeline projects in Canada that have stalled in the face of public resistance – Energy East, Trans Mountain and Northern Gateway.

“I think what is really telling is that Canadians don’t want pipelines in their own country,” says Liz Kirkwood, executive director of For Love of Water, another Michigan group opposing Line 5. “It’s enormously disappointing to see the Canadian government failing to stand up for the Great Lakes.”

Indigenous protesters chain themselves and a kayak to the entrance of the White House on June 30 to oppose Enbridge's Line 3 pipeline.Alex Brandon/The Associated Press

The U.S., meanwhile, is just as divided. Some traditionally Democratic trade unions, for instance, stand behind Enbridge.

Justin Donley, president of the United Steelworkers local at a refinery in Toledo, Ohio, says that without the pipeline, he and more than 1,000 co-workers would lose their jobs. There isn’t enough capacity on other lines to make up the lack of crude, he says, and the refinery doesn’t have the facilities to process shipments from more tanker trucks.

Mr. Donley, a Toledo native, has worked at the refinery for 18 years. His father and brother work there too. With annual pay averaging US$86,000, he says, the refinery is the best job available in this small industrial city. Without it, he would have to move to find work that pays well enough to save up for his two young sons’ educations.

“I’d have to start over,” he says, standing next to his pickup truck in the refinery parking lot one humid spring evening, the complex’s persistent hum and burning flares in the background. “If I want to keep the lifestyle I have, and provide for my family, I’m going to have to pick up and move.”

Mr. Donley takes the environmentalists’ point that the world is moving away from fossil fuels. But that shift is a long way off, he says, as evidenced by the panic over the brief closing of the Colonial Pipeline in the U.S. Southeast by a cyberattack in May.

“There’s a transition happening, I won’t deny that,” he says. “But even if we went today to all-electric vehicles, that infrastructure doesn’t exist.”

Rich Studley, president of the Michigan Chamber of Commerce, is less conciliatory. He accuses Ms. Whitmer of trying to please “environmental extremists.”

“The path the Governor is on, if even half the governors in the country followed it, would lead to price hikes, lost jobs, lost revenue, energy shortages,” he says. “It would be anarchy.”

'Water is your quality of life,' Ms. Peek says.Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

Patty Peek has heard these warnings, and they don’t much bother her. If need be, she says, she’ll find a different supplier for the propane she uses to heat her house. Such inconveniences are less concerning than the threat the pipeline poses to the waters that attracted her to this home.

She grew up in Michigan’s industrial south, but spent her spare time since childhood sailing and water skiing on the state’s lakes. Her career in nursing included running village clinics in Siberia, Jamaica and Ukraine, where she further learned the value of clean water, seeing how its absence held back development. In 2006, she headed north to fulfill a decades-long dream of living at the edge of a lake.

Now, she doesn’t want to take any risk of losing one of the things that defines her, and this place.

“Water is your quality of life,” she says, sitting outside her house, as waves lap the nearby shoreline. “You take the water away from people in Michigan, and what they know and love is gone.”

The Decibel: Adrian Morrow on Line 5

On this episode of The Globe and Mail’s news podcast, Tamara Khandaker asks Washington correspondent Adrian Morrow about what makes Michigan’s feud over Line 5 different from other pipeline battles. Subscribe here for more episodes.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.