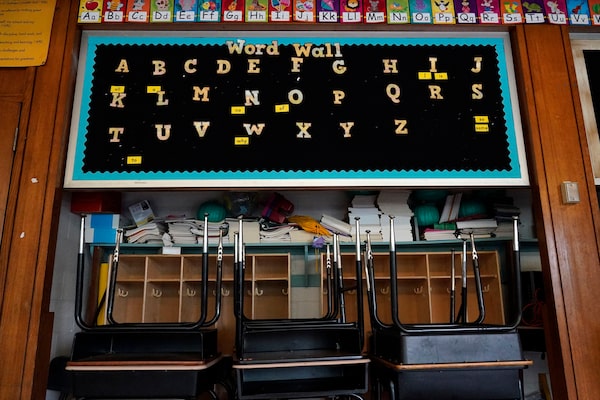

Testing of thousands of nine-year-old students in the U.S. at the beginning of this year showed a fall in reading scores relative to 2020 that is the largest since 1990, and the first decline in math scores.Nam Y. Huh/The Associated Press

Two years after the spread of COVID-19 prompted administrators around the world to close schools, students in the U.S. have seen some of the worst drops in test scores on record, underlining the severity and longevity of the pandemic’s toll on children.

Testing of thousands of nine-year-old students in the U.S. at the beginning of this year by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which bills itself the “nation’s report card,” showed a fall in reading scores relative to 2020 that is the largest since 1990, and the first decline in math scores.

The tumble in performance, released in a new report this week, was far more acute for students in racialized communities and those already struggling in school. Black students saw a 13-point fall in math, compared with six points for white children. Hispanic students also had an outsized decline. In reading, the fall in scores was five times more pronounced for students in the lowest decile compared with those in the top decile. Math scores saw a fourfold gap in the decline between upper- and lower-performance students.

The pandemic’s “impact on students and teachers and schools is unprecedented,” said Peggy Carr, commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, which conducts the national report-card testing. The data show the unfolding of “long-lasting effects” in education, she said in an interview.

The national assessment was not conducted in 2021, meaning the scores capture how students fared after the return to more normal operations for many cities and schools. Nonetheless, the results show the pandemic has reversed years “of slow, steady progress,” said Thurston Domina, an education scholar at the University of North Carolina. Although virtually all groups showed declines, the setback in scores came primarily from students who already had lower marks.

“If you’re a high-achieving kid, if you’re in the top 10 per cent nationally, this is a bump in the road,” Prof. Domina said. “But it’s a big step back for kids at the bottom of the distribution.”

Average reading and mathematics scores for nine-year-old students in the U.S.

1980 to 2022

Mathematics

Reading

245

240

235

234

230

225

220

215

215

210

205

‘90

‘92

‘94

‘96

‘99

‘04

‘08

‘12

‘20

‘22

Reading and mathematics scores for nine-year-old students in the U.S., by race and percentile

2020 vs. 2022

By race:

White

Black

Hispanic

Other

READING

MATH

253

250

250

247

244

232

229

230

227

225

228

223

223

212

210

210

205

204

199

190

2020

2022

2020

2022

50th

10th

90th

By percentile:

READING

MATH

290

286

283

267

265

250

245

238

224

219

210

191

178

170

164

155

130

2020

2022

2020

2022

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF EDUCATIONAL PROGRESS

Average reading and mathematics scores for nine-year-old students in the U.S.

1980 to 2022

Mathematics

Reading

245

240

235

234

230

225

220

215

215

210

205

‘90

‘92

‘94

‘96

‘99

‘04

‘08

‘12

‘20

‘22

Reading and mathematics scores for nine-year-old students in the U.S., by race and percentile

2020 vs. 2022

White

Black

Hispanic

Other

By race:

READING

MATH

253

250

250

247

244

232

229

230

227

225

228

223

223

212

210

210

205

204

199

190

2020

2022

2020

2022

90th

50th

10th

By percentile:

READING

MATH

290

286

283

267

265

250

245

238

224

219

210

191

178

170

164

155

130

2020

2022

2020

2022

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF EDUCATIONAL PROGRESS

Average reading and mathematics scores for nine-year-old students in the U.S.

1980 to 2022

Mathematics

Reading

245

240

235

234

230

225

220

215

215

210

205

1990

1992

1994

1996

1999

2004

2008

2012

2020

2022

Reading and mathematics scores for nine-year-old students in the U.S., by race and percentile

2020 vs. 2022

White

Other

Black

Hispanic

By race:

READING

MATH

253

250

250

247

244

232

229

230

227

225

228

223

223

212

210

210

205

204

199

190

2020

2022

2020

2022

90th

50th

10th

By percentile:

READING

MATH

290

286

283

267

265

250

245

238

224

219

210

191

178

170

164

155

130

2020

2022

2020

2022

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF EDUCATIONAL PROGRESS

The U.S. scores show results broadly similar to testing done in other Western countries, including in Europe. In Canada, where data are scarcer, it is more difficult to ascertain the pandemic effect on classrooms, although some indicators suggest notable delays. A University of Alberta study found that students in Grades 1 and 2 in the Edmonton area performed, on average, eight months to a full year below grade level on reading tasks by the end of the 2020-21 academic year.

The U.S. scores offer hope that time will bring improvements. They suggest students are now, on average, behind “in the order of a couple of months,” Prof. Domina said.

“I don’t think that we have a generation that’s lost. But I think we have a real challenge on our hands. And we just have to collectively focus our attention on our kids,” he said.

Other U.S. research points to a recovery in progress – although not for all students. The NWEA, an educational research group formerly known as the Northwest Evaluation Association, found that last year, students in Grades 2 through 5 made back about a quarter of the decline in reading and math scores compared with the first pandemic year. At that rate, it will take an estimated three to five years to close the gap.

But for middle-school children, “we see some stagnation, where the gaps are staying pretty consistent,” said Karyn Lewis, director of the Center for School and Student Progress at NWEA. It’s not clear why – perhaps pandemic disruptions hit them harder, or perhaps schools did more to intervene with younger grades – but for those older students, a rebound is expected to take far longer.

In the United States, the drops in educational achievement have only added to the heated debate over the pandemic response.

On Thursday, the Joe Biden White House sought to deflect blame for the poor test scores, with press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre faulting the policies of Donald Trump. “We must repair the damage that was done by the last administration,” she said on Thursday.

While he was president, Mr. Trump decried many pandemic measures and urged schools to stay open. On average, regions that voted for Mr. Trump had more in-person instruction. But keeping children in class turned out to be “the correct instinct,” said Emily Oster, an economist at Brown University.

“Remote learning harmed achievement and growth,” added Ms. Lewis. “We consistently see that when schools were remote for longer, there were larger negative impacts.”

The NAEP study showed that among students learning from home, those with lower scores tended to have worse access to teachers, computers, high-speed internet and a quiet place to work.

But the NAEP also found exceptions that suggest remote learning was not universally harmful. Ethnic groups with higher rates of remote learning – Asian communities, in particular – “scored the highest,” Ms. Carr said.

For educational authorities around the world, a key question now is how to reverse the effects of the pandemic. Work by Ms. Carr’s centre shows one of the most promising measures involves bringing in extra tutors. But teacher shortages in parts of the United States have grown so acute that some Texas districts are planning for just four days of instruction a week, while Florida schools are hiring military veterans without educational backgrounds.

Still, Ms. Lewis cautioned against fear that such setbacks are intractable. School performance dropped for students in New Orleans affected by Hurricane Katrina, for example.

But “research also shows those kids eventually bounce back,” she said. “It takes some time, but it’s not impossible.”

With a report from Caroline Alphonso

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.