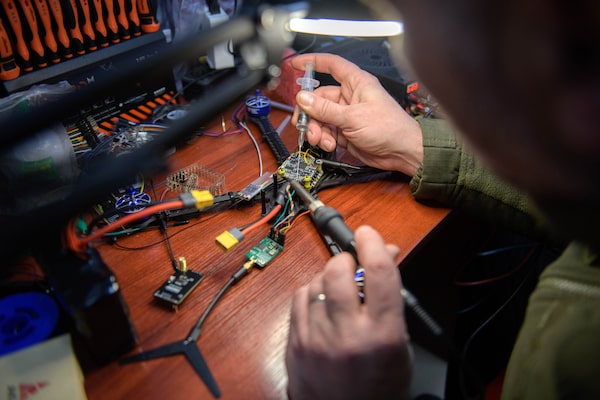

Ukrainians work at a secret laboratory in Kyiv where military personnel learn to make first-person-view drones, or FPVs, for the war against Russia.Olga Ivashchenko/The Globe and Mail

Oleksandr Kamyshin is in a good mood – or as good as can be expected for the man leading Ukraine’s tortuous industrial effort to narrow Russia’s formidable lead in weapons production.

In the previous three days, Ukrainian-made drones scored two hits that put a smile on the Strategic Industries Minister’s face, as well as that of every other member of President Volodymyr Zelensky’s war cabinet.

The first came some time after midnight on Feb. 1, when naval drones sank the Ivanovets, a Russian missile corvette, in the waters just off western Crimea. Ukraine’s military intelligence agency, with characteristic wry understatement, said the small warship “suffered damage incompatible with further movement.”

The second came three days later when two long-range suicide drones struck the largest oil refinery in southern Russia, in Volgograd. While the refinery, owned by Lukoil, appears not to have suffered significant damage, the attack once again showed that Ukraine is now capable of hitting targets deep inside Russia, opening a new phase of the war. Ukraine’s military commanders are fond of calling homegrown drones “our main export to Russia.”

'Our drones go into Russia almost every single night,' Strategic Industries Minister Oleksandr Kamyshin says.Olga Ivashchenko/The Globe and Mail

Drone attacks inside Russia have become regular, morale-lifting events in recent months, even as Ukraine’s military struggles to hold its ground along the 1,000-kilometre-long front after its failed summer and autumn counteroffensive. A Jan. 18 attack on an oil terminal near St. Petersburg saw drones travel 1,000 kilometres north of the Ukrainian border, a distance considered impossible a year ago. “Our drones go into Russia almost every single night,” Mr. Kamyshin told The Globe and Mail. “Some missions have 100 per cent success.”

The timing of the attacks is no accident. It is only in the past few months that Ukraine’s drone production has come on strong. Mr. Kamyshin said the country is on course to produce a million or more of the machines this year. They will range from small, light surveillance drones that cost a few hundred dollars apiece to heavy, deadly long-range versions that are estimated to cost about US$200,000.

On Tuesday, Mr. Zelensky, demanding an even more ambitious drone effort, announced the creation of an armed forces branch devoted exclusively to the weapons. “This year must be decisive in a great many aspects,” he said in his nightly video address. “And clearly on the battlefield. Drone systems have shown their effectiveness on land, in the skies and on the seas.”

The Ukrainian long-range drones that are taking

the war deep inside Russia

The new drones have ranges that were impossible to achieve a year ago and are credited with hitting refineries as far north as St. Petersburg

DRONE

PAYLOAD (KG)

RANGE (KM}

20

1,000

UJ-26 Beaver

20

800

UJ-22 Airborne

10

800

UJ-25 Skyline

32 to 70

750

AQ-400 Scythe

3

300

Morok

Payloads and ranges approximate. Not to scale.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: H.I. SUTTON; DEFENSE MIRROR

The Ukrainian long-range drones that are taking

the war deep inside Russia

The new drones have ranges that were impossible to achieve a year ago and are credited with hitting refineries as far north as St. Petersburg

DRONE

PAYLOAD (KG)

RANGE (KM}

20

1,000

UJ-26 Beaver

20

800

UJ-22 Airborne

10

800

UJ-25 Skyline

32 to 70

750

AQ-400 Scythe

3

300

Morok

Payloads and ranges approximate. Not to scale.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: H.I. SUTTON; DEFENSE MIRROR

The Ukrainian long-range drones that are taking the war deep inside Russia

The new drones have ranges that were impossible to achieve a year ago and are credited with hitting refineries as far north as St. Petersburg

DRONE

SILHOUETTE

PAYLOAD (KG)

RANGE (KM}

20

1,000

UJ-26 Beaver

20

800

UJ-22 Airborne

10

800

UJ-25 Skyline

32 to 70

750

AQ-400 Scythe

3

300

Morok

Payloads and ranges approximate. Not to scale.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: H.I. SUTTON; DEFENSE MIRROR

The problem is that drones are one of the few bright spots in Ukraine’s defence industry. The country produces shockingly few artillery shells – notably of the 155 mm NATO-standard variety – armoured personnel carriers, electronic anti-warfare systems, aircraft of all types and anti-aircraft missiles.

Estonian Minister of Defence Hanno Pevkur has said that Ukrainian troops are firing only about a third as many rounds as the Russians because of severe ammunition shortages. Various estimates from NATO countries give Russia a 5-to-1 and even 10-to-1 advantage in shells. Russia’s artillery factories are intact and operating around the clock as the economy goes into full-war footing.

It is Mr. Kamyshin’s job to ramp up weapons production fast to overcome Russia’s enormous advantage. It won’t be easy, especially since Ukraine is perennially short of funding. “Our armed forces need everything,” he said. “We have several times less than what they need.”

Ukrainian servicemen fly a Vampire unmanned aerial vehicle near the front lines in Zaporizhzhia on Feb. 2. A day earlier, Ukraine's drone fighters sank a Russian missile corvette in the Black Sea.Reuters

Mr. Kamyshin, 39, met with The Globe at the Kyiv Food Market, a cavernous former armoury built at the end of the 18th century. It is full of restaurants, bars and bakeries. The market is famous – or infamous – for having hosted the world’s longest news conference. In late 2019, about half a year after he was elected President, Mr. Zelensky took questions for 14 hours in the food court from almost 300 Ukrainian and international journalists.

When Mr. Kamyshin entered, no one took notice of him, even though he is tall and imposing. He arrived looking like a member of a motorcycle gang. Clad entirely in black, he sported a black beard and a hair braid. He is a finance graduate, worked as an auditor for KPMG and, later, as an investment banker. He is married and has two teenage sons.

Admired by Mr. Zelensky for his financial and management skills, he was appointed CEO of state-owned Ukrainian Railways in mid-2021, about half a year before Russian President Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale invasion, and won international kudos for keeping the trains rolling during the war. The train network delivered millions of refugees west, to the borders of the European Union, and weapons and others supplies east, to the front lines.

“We had zero casualties on the rails in the first year of the war,” Mr. Kamyshin said.

Last March, when weapons were running low after a year of fighting, Mr. Zelensky pushed him into cabinet with instructions to build Ukraine’s arsenal. He hasn’t had a day off since then.

Becoming self-sufficient, or at least largely so, in key weapons such as drones and artillery shells was a matter of urgency, as neither Ukraine nor the NATO countries had the ability to produce such weapons and ammunition in sufficient numbers. At the start of the war, the United States was producing about 14,000 155 mm shells a month; it has increased its output now to about 30,000. NATO officials have said Ukraine can go through that many shells in several days.

A serviceman in Zaporizhzhia prepares 155-mm shells, which Ukrainian forces can use tens of thousands of within a few days, according to NATO estimates.Reuters

Since NATO countries could not deliver all the weapons Ukraine needed, Kyiv knew it had to build them itself. Weapons produced domestically would both boost supply and lower costs.

This is where the “cost-to-kill” ratio comes in. It is an obsession of Mr. Kamyshin’s and Ukraine’s top finance officials. In short, the cheaper it is to kill Russians, the longer Ukraine can keep fighting.

Mr. Kamyshin gave an example. One Ukrainian-built Stugna anti-tank missile, the rough equivalent of the U.S.-made Javelin, costs US$4,163 to kill one Russian soldier. His calculation is based on the price of the weapon, its success ratio – the proportion of shots that hit their target – and how many men it typically kills when it does.

By way of comparison, a first-person-view (FPV) drone, which is controlled by an operator on the ground who sees what the drone’s camera sees, costs only US$1,700 a kill. The conclusion is obvious: Build more and better drones, which is exactly what Ukraine is doing. Mr. Kamyshin thinks the drones’ cost-to-kill ratio could drop significantly as production soars and lethality improves.

Military sources say one Ukrainian company alone is producing 45,000 cheap drones a month. “Production has increased by 100 times since June, 2022,” said Deputy Defence Minister Kateryna Chernohorenko. “We have hundreds of drone factories.”

Thousands of civilians are getting into the drone game. In Kharkiv, in northeastern Ukraine, Radomyr Tyutyunnyk, a 16-year-old student, assembled a team of five colleagues to make short-range, anti-personnel drones that can carry a bomb weighing a bit less than a kilogram. The machines, funded by private donations, use Chinese parts and cost about US$375 apiece. “Our goal is to make 10,000 of them a year,” he told The Globe in a video interview. “I am doing this because I want to help our armed force and I want to be part of our victory.”

At the secret lab in Kyiv, military personnel and students are exploring new ways to make drones that can hold their own against multimillion-dollar Russian equipment.Olga Ivashchenko/The Globe and Mail

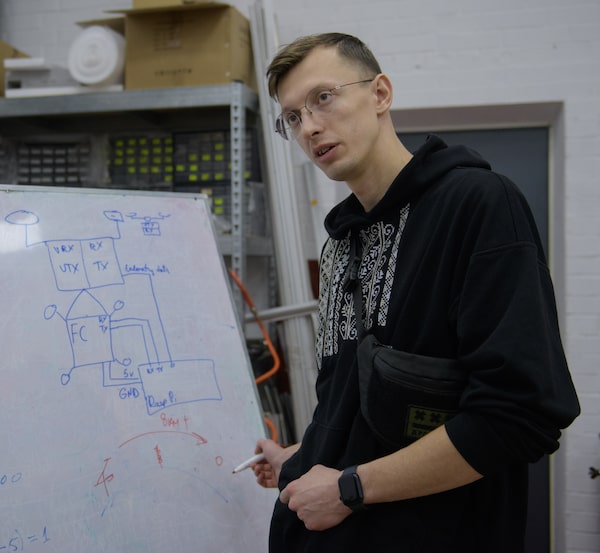

Maxim Sheremet, who runs the two-room lab, knows that Ukraine has far to go before it can catch up with Russia in the drone arms race.Olga Ivashchenko/The Globe and Mail

The Globe visited a secret site in suburban Kyiv where military personnel learn how to assemble basic FPV drones. The two-room laboratory, stuffed with computers and simple tools, is run by Maxim Sheremet, 27, who has a PhD in avionics. “The goal is to make drones cheaper, more efficient and less able to be tracked by the enemy,” he said. “Hundred-dollar drones can take out million-dollar armoured vehicles.”

He said he has another operation, known as Drone Space, where thousands of drones are produced. One of the models, he said, can carry a 16-kilogram bomb for eight kilometres. Still, despite the production and technological ramp-up, he said, Ukraine has a long way to go before it can match Russian drone capabilities. “Russia every day opens new drone labs and creates new drones,” he said. “Every day, they produce five times more drones than us.”

NATO is helping Ukraine’s drone effort through the “Innovation Dialogue” it launched last year. While the alliance itself cannot supply drones to Ukraine – only the individual members can do that – it has created a platform to help Ukrainian startups, including those making drones, find private financing and identify new technologies.

Military personnel patrol outside Patriot air-defence equipment during training at the Warsaw airport in 2023.Kacper Pempel/Reuters

Making drones in vast quantities is not the only job on Mr. Kamyshin’s to-do list. He is trying to convince the United States to grant licences to build advanced weapons, such as air-defence systems. But securing licences is proving to be a slow process that, in some instances, would require congressional approval. Ukraine has, however, gained the right to adapt some old, surplus U.S. weapons; for instance, it is adapting the Sidewinder air-to-air missile, which first flew in the 1950s, to become a ground-to-air missile to take out Russian aircraft.

Ukraine is also begging for licences for armoured vehicles. Kyiv would love to have the right to build Germany’s latest-generation Lynx fighting vehicle. Ukraine has plenty of metal-bashing expertise and idle factories where they could be assembled. But getting the licence and access to the technology to produce 155 mm shells, including their propellant, is the priority as artillery stockpiles run short.

Mr. Kamyshin knows he is in the hot seat as the war enters its third year and the weapons shortage threatens to hand the tactical advantage to the Russians. He has a reputation for being iron-willed, as he was at Ukraine Railways, and has a talent for surrounding himself with iron-willed assistants, so the government’s expectations and hopes are high. “We have to build, and are building, the arsenal for the free world,” he said.

War in Ukraine: More from The Globe and Mail

When Ksenia Koldin was separated from her brother in a Russian-occupied area of Kharkiv, she went on a mission to get him out of the network of “summer camps” Russia has built to assimilate Ukrainian youth. The Globe’s Mark MacKinnon shares their story. Subscribe for more episodes.

Ukraine’s oligarchs are no longer considered above the law

Making peace with Russia now would be surrender, Ukrainian winner of Nobel Peace Prize says

Kyiv’s mayor worries Ukraine under Zelensky is getting more autocratic