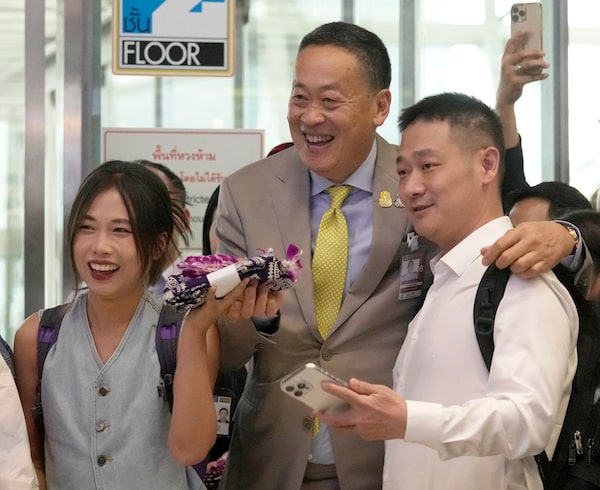

Chinese tourists dance with puppets on Sept. 25 at Suvarnabhumi International, the main airport serving Thailand's capital of Bangkok. The new Thai government granted temporary visa-free entry from China, part of its plans to revive the country's tourism sector.Sakchai Lalit/The Associated Press

Chinese tourists arriving at Bangkok’s international airport Monday were greeted by a crowd of journalists, beaming staff handing out purple and white orchids, and Thailand’s Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin, who hailed their presence as proof of the kingdom’s resurgence as a travel destination following a pandemic-induced slump.

Tourism previously accounted for as much as 18 per cent of Thailand’s GDP, and Mr. Srettha has promised greater support for the travel sector. As part of this, his government has dropped visa requirements for Chinese travellers, some 11 million of whom visited in 2019, making up around 30 per cent of all tourists to the kingdom.

But for some in China, a country once associated with beaches, food and elephants has acquired a far darker reputation, amid reports of criminal gangs kidnapping Chinese citizens to work in scam call centres in lawless parts of Southeast Asia.

“The whole region has become a no-go zone,” said Zhang Ziwei, a 26-year-old shop owner in Haikou, a city on the southern island province of Hainan. “I don’t think the visa-free policy will be enough.”

Chinese tourists, holding free souvenirs, takes pictures with Thailand's Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin at the airport.Sakchai Lalit/The Associated Press

According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, around 200,000 people are currently being held by criminal gangs in slave-like conditions in Myanmar and Cambodia, forced to make calls pitching dodgy investments, illegal gambling and romance scams. The call centres generate billions of dollars in revenue a year, the UN said.

Many victims are lured by promises of well-paying jobs, while a minority report being kidnapped while visiting parts of Southeast Asia. Chinese nationals and English-speakers from places such as Hong Kong and the Philippines, are particularly prized given the respective size of those markets for scam calls.

As the scale of the crisis has become clear in the past year, police in many Asian countries have set up dedicated task forces to try and rescue their nationals. China has also pressed governments in the region to crack down, and even non-state actors: Earlier this month, an ethnic militia with close ties to Beijing in eastern Myanmar’s Shan State raided several call centres and repatriated more than 1,200 Chinese nationals.

But with Myanmar racked by civil war, and limited government control in border regions of Cambodia and Laos, tackling the issue has proven extremely difficult.

Victims who made it home have tried to raise the alarm. In a series of blog posts and media reports this month, a postdoctoral researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, one of the country’s most prestigious institutions, recounted how he had ended up in a call centre in Myanmar, forced to work 15-hour days for a year tricking lonely men into parting with their money online, before his family paid a $10,000 ransom.

According to the man – whose story was confirmed by China’s embassy to Thailand – he had responded to an advert for a job in Singapore. But after several purported delays in securing a visa, his employer suggested he start work for them in a town near the Myanmar border. On arrival in August, 2022, he was trafficked across and soon discovered he was trapped.

Kidnap scams have even been the subject of a blockbuster movie: No More Bets tells the story of a Chinese computer programmer trafficked to an unnamed Southeast Asian country and forced to target gambling addicts online. The victims are eventually saved by the Chinese police.

So far, only 2.3 million Chinese tourists have travelled to Thailand since January, and the kingdom will struggle to hit a target of five million this year. But Wolfgang Georg Arlt, head of the China Outbound Tourism Research Institute, was skeptical that this was wholly owing to fears of kidnapping.

Before the pandemic, he said, most Chinese tourism to Thailand was done through cheap group tours that provided little benefit to the host country and which the Thai government had begun cracking down on. As the Chinese tourist market has matured, such tours have begun to fall out of fashion and solo travel is on the rise, but the numbers have yet to catch up.

Ms. Zhang, the Haikou shopkeeper, acknowledged Thailand was “getting its reputation hurt by crimes it barely has anything to do with.” She said she had enjoyed a trip to Bangkok in 2019 and never felt in danger, but the proximity to Myanmar was too great for her to risk travelling there again.

David Gu, a 32-year-old recruiter living in Shenzhen, disagreed, describing Thailand’s visa-free policy as “great news.”

“Anyone who has queued for visa on arrival will understand how much this policy benefits us,” he told The Globe and Mail, adding Thailand was his “favourite country in Asia.”

Mr. Gu is planning to return in November and said his main concern was that prices would spike as a result of the new policy. He wasn’t concerned by the scam call centres, adding public awareness of the potential danger was much higher and there was little risk in Thailand itself.

“No place is absolutely safe,” he added. “We don’t have to stop eating for fear of choking.”

With files from Alexandra Li in Beijing