April, 1959: Prince Philip and Queen Elizabeth II stand for a portrait at Buckingham Palace by a Toronto photographer, taken ahead of a royal tour of Canada.Donald McKague

Tall, blond and dashing, HRH Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, had the looks and breeding of a Prince Charming, but was woefully deficient in the other fairy tale attributes: a kingdom and boundless riches. Still, he won the heart of a princess, the future Queen Elizabeth II. As one of very few male consorts in British history, Philip upheld his constitutional role three times as long as his most famous predecessor, Albert, Prince consort to Queen Victoria.

The 99-year-old Philip, whose death at Windsor Castle was announced by Buckingham Palace on Friday, was married to the Queen for more than 70 years. He was in robust health well into his late 80s, when he developed a series of heart issues and other health problems. This past February, he was admitted to a private London hospital after feeling unwell (which officials said was not related to COVID-19) before returning to Windsor Castle in mid-March.

He had announced his retirement from royal duties in May, 2017. He made an exception for family celebrations such as the wedding of his grandson Prince Harry to Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, a year later. He was privately distressed but publicly mum when the couple announced they were taking “a step back” as senior members of the Royal Family on Jan. 8, 2020.

“For Philip, whose entire existence has been based on a devotion to doing his duty,” Ingrid Seward writes in her 2020 biography Prince Philip Revealed, “it appeared that his grandson had abdicated his for the sake of his marriage to an American divorcee in much the same way as Edward VIII gave up his crown to marry Wallis Simpson in 1936.”

Philip leaves the Queen, his four children, several grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and his extended family. Funeral arrangements are pending.

Born in Greece, a country riven by civil war in the aftermath of the First World War, Philip grew up stateless and poor in a splintered family in which one of his disaffected parents spent time in an asylum and the other frequented the gaming tables at Monte Carlo.

The Royal Navy and his uncle, Louis Mountbatten, were the making of him as an officer and a courtier. A promising naval officer who saw distinguished service during the Second World War, Philip found his world changed irrevocably with his wife’s accession to the throne on her father’s death in February, 1952.

As chairman of his wife’s Coronation Commission, he devoted himself to organizing the public spectacle with military precision.

Philip himself was neither crowned nor anointed at the Westminster Abbey ceremony on June 2, 1953. Instead, he was the first subject to pay homage to the newly crowned Queen.

And then, in a private, but widely circulated aside, he turned to his wife, weighted down by all her regalia, and asked: “Where did you get that hat?”

June 2, 1953: The newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II waves from the balcony at Buckingham Palace with Prince Philip at her side.Associated Press

Prince Philip and the Queen attend the official re-opening of the restored tea clipper Cutty Sark in Greenwich on April 25, 2012.PAUL HACKETT/Reuters

For the rest of his life, he walked dutifully to her side and one pace behind at the opening of bridges and factories, on state occasions in Britain and on gruelling royal tours around the world.

His demeanour, which could be haughty and impatient, and his tongue, which could be blistering and intemperate, proved less obedient.

Giving up his naval career to be the Queen’s consort was a hard choice, but it is one he bore without public complaint. An avid sportsman who loved to hunt, sail and fly planes, he played polo until he was 50, when he began driving a coach and four in competition, even helping to draft the sport’s rule book.

A strong advocate of British scientific and technical innovation, wildlife protection and conservation, he was the patron or president of some 800 organizations. Those with which he was most closely associated are the World Wildlife Fund and The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award, which recognizes young people who have completed a community service or athletic program of self-directed activities.

Despite rumours of mistresses (including the actress Merle Oberon and his wife’s cousin, Princess Alexandra) and squabbles with his children over their choices of careers and mates, he served his Queen and his country with vigorous loyalty.

He grew into the job and lived up to the vow he made at the Queen’s coronation, “to become your liege man of life and limb, and of earthly worship; and faith and truth I will bear unto you, to live and die, against all manner of folks” – even if some of those folks turned out to be his own wayward offspring.

Left: Baby Philip, then a year old, in 1922. Middle: Philip as a child in the national dress of his native Greece. Right: Philip, a student at Gordonstoune school in Scotland, suits up for a production of Macbeth for charity.Associated Press, Fox Photos

Early life

Philippos Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg was born on the Greek island of Corfu in the Ionian Sea on June 10, 1921, the fifth child and only son of Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark and the Princess Alice of Battenberg. His mother and his four older sisters doted on the golden-haired boy.

Through his mother, he was a nephew of Lord Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma, and a great-great grandchild of Queen Victoria, and thus in line of succession to the British Crown, albeit with faint hope of ever acceding to the throne.

Philip was only 18 months old when the Greek monarchy was overthrown by a military junta, which forced King Constantine I, Philip’s uncle, to abdicate on Sept. 22, 1922. After a revolutionary court sentenced Philip’s father, Prince Andrew, to death, King George V dispatched the Cruiser HMS Calypso to evacuate the family.

They settled into a modest villa on the outskirts of Paris, but Philip’s home life continued to be chaotic. His parents separated when he was 9, with his mother finding solace in a nunnery while his father sought salvation in Monte Carlo and eventually died in the arms of his mistress. Philip was sent to Cheam, an English boarding school known for cold showers, bad food, corporal punishment and rote learning of Greek and Latin – a regimen in which he thrived.

In 1933, just as Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, Philip was sent to a German boarding school owned by his elder sister and her husband. Although some observers have tried to use the school to link Philip to the Nazis, the truth is more prosaic: His impoverished family wanted to save on the school fees.

The headmaster was Kurt Hahn, an inspirational teacher who believed in combining leadership opportunities and physical training with a classical curriculum. Facing persecution in Germany, Hahn fled to Morayshire, Scotland, where he established Gordonstoun School. Philip soon followed. He so loved the rugged atmosphere of Gordonstoun that he later sent his own sons there – however unwilling in the case of Charles.

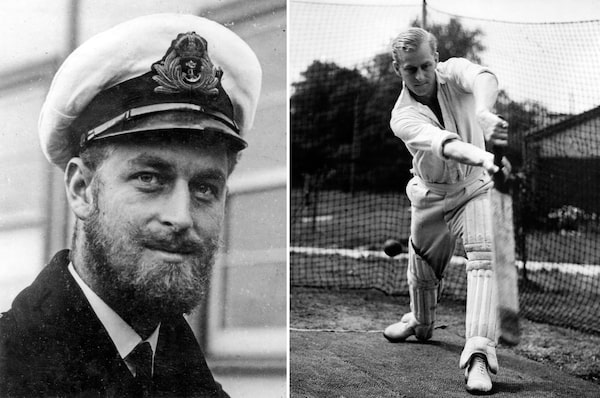

Left: Philip during a naval visit to Melbourne in August, 1945. Right: The young lieutenant bats at the nets during cricket practice at the Petty Officers’ Training Centre in Corsham, Wiltshire, in July, 1947.Associated Press

Military service

After leaving Gordonstoun in 1938 as “Guardian” or head boy, Philip was accepted into the Royal Navy, a month before his 18th birthday, as a special entry cadet. He attended the Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth for three months and was awarded the King’s Dirk as the best all-round cadet in his term.

Commissioned as a midshipman in January, 1940, Philip rose through the ranks to 1st lieutenant and saw distinguished service in the defence of Malta, convoy duty in the North Sea, the Allied invasion of Sicily and the Far East with the British Pacific Fleet. He was in Tokyo Bay, as aide-de-camp to Lord Mountbatten, then supreme Allied commander of the Southeast Asia Theatre, when the Japanese surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945.

He continued his naval career after the war and his 1947 marriage to Princess Elizabeth. In January, 1952, Philip was promoted to commander. Later that year he took an indefinite leave from the navy to accompany the Princess on a royal tour of Australia and New Zealand. They were staying at Sagana Lodge in Kenya when word came of King George VI’s death from lung cancer on Feb. 6, 1952.

Philip’s active service days ended with his wife’s accession to the throne. Nevertheless, he continued to hold the ranks of admiral of the fleet in the Royal Navy, a field marshal in the British Army and a marshal of the Royal Air Force. He also kept up his military skills, gaining his RAF wings in 1953, his helicopter wings in 1956 and his private pilot’s licence in 1959. He had notched 5,986 hours in 59 types of aircraft before his short final flight at the age of 76, on Aug. 11, 1997, from Carlisle to the island of Islay in Scotland.

Nov. 20, 1947: Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip pose for this official picture in Buckingham Palace after their return from their wedding in Westminster Abbey.Associated Press

Marriage and family

Philip first met Princess Elizabeth at the wedding of his cousin, Princess Marina of Greece, to her cousin, the Duke of Kent, at Westminster Abbey on Nov. 29, 1934. He was 13 and she was eight. The first time they noticed each other was five years later, when Lord Mountbatten contrived to have her visit the Naval College at Dartmouth, where his nephew, Philip, was her designated escort.

She was smitten, according to her gossipy nanny, and the two exchanged letters during the war. Still, eight years elapsed before King George VI announced the engagement of his elder daughter to Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten R.N. on July 9, 1947. The 20-year-old princess and her 25-year-old swain made their first public appearance as an affianced couple the next day at a Buckingham Palace garden party.

Her platinum and diamond engagement ring was made of diamonds taken from a tiara that had belonged to Philip’s mother. After the couple attended the opening of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Oklahoma! in London that year, the song People Will Say We’re In Love became a hit with them as well as many others.

The match was controversial: Philip was Greek Orthodox, with no financial resources behind him, had sisters who had married Nazi supporters and was known to large segments of the public as “Phil the Greek.” The Princess’s mother was reported to have strongly opposed the marriage. Philip had overcome one of the hurdles by becoming a naturalized British citizen in February, 1947. That’s when he dropped his family name, Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, and adopted Mountbatten, his uncle’s surname, as his own.

Flashback: The wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip Mountbatten in 1947

The Globe and Mail

Two thousand guests attended the wedding on Nov. 20 at Westminster Abbey. The bridegroom, who had given up smoking that morning to please his bride, fortified himself with a gin and tonic and donned full-dress naval uniform. He arrived at the altar carrying the weight of the three titles the bride’s father had just bestowed on him – HRH The Prince Philip, The Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Merioneth and Baron Greenwich, KG, KT, OM, CBE, AC, QSO, PC and officially a Prince of the United Kingdom and First Gentleman of the Realm.

The newlyweds spent their wedding night at Broadlands in Hampshire, home of Philip’s uncle, Lord Mountbatten, and then travelled to Scotland to stay at Birkhall on the Royal Family’s Balmoral Estate.

Early in 1948, the couple leased their first marital home, Windlesham Moor, in Surrey, near Windsor Castle, where they stayed until they moved to Clarence House in early summer 1949. After her father’s death, the Queen moved with her family into Buckingham Palace.

The couple hold their children Prince Charles and Princess Anne at Clarence House.EDDIE WORTH/The Associated Press

Their son Charles was born on Nov. 14, 1948, followed less than two years later by their daughter, Anne, on Aug. 15, 1950. Their third child, Andrew, was born Feb. 19, 1960, followed four years later, on March 10, 1964, by their youngest child, Edward.

The marriage did not escape gossip about other women. Rumours of a royal rift were fuelled in 1956-57, when Philip made a round-the-world voyage on board HMY Britannia, visiting remote islands of the Commonwealth, on a trip that kept him away from home for four months, including over Christmas. While he said later that this voyage gave him his first awareness of the effects of industrialization on the natural environment, observers at the time used his absence to point to trouble in the royal marriage. An exasperated Philip lashed out at the press with complaints about the “bloody lies that you people print to make money.”

Prince Charles and Prince Philip wear the wings of the Royal Air Force as they chat at the RAF College in Cranwell on Aug. 20, 1971, after the heir apparent to the throne received his wings.Associated Press

As a father, Philip was said to be authoritarian and something of a bully, especially with his sons, and to favour his only daughter, Anne, who like him, is horsey, workaholic, forthright and sometimes surly. He wanted his sons to be sporty, rugged and combative, perhaps hoping they would aspire to the military career that he himself had had to forgo.

Prince Charles has admitted that his father readily told him to “shut up” when he was growing up. Even as an adult, Charles’s eyes would well with tears during a tongue lashing from Philip. He defied his father on only two major occasions – a state funeral for his former wife, Diana, and marriage to his long-time mistress, Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall – and each time he won the day.

Philip told Edward, his youngest son, to “shape up” when he quit the Royal Marines in 1987. Generally, the press sided with the son, with the Daily Mail telling Philip “to act like a father and not a bloody general.”

As for the royal divorces, of which there have been three among the Queen’s own children, Philip’s exhortations to put duty before happiness ricocheted into bad press for him. He liked jokey, casual Sarah Ferguson, but her public shenanigans, which embarrassed the “family business,” embittered him toward her. When Diana was winning the photo-op war against Charles, after their separation and divorce, and accusing the Royal Family of being cold and unfeeling, Philip apparently told his son to “bloody well take charge,” a feat that was beyond Charles with his willful ex-wife.

Prince Charles and Prince Philip stand behind a smiling Diana, Princess of Wales, as she holds Prince William after his christening on Aug. 4, 1982.Associated Press

Despite the rumours of infidelity and the usual parental disputes about children, the Queen and Philip’s long marriage was a happy union. Early on, they reached an accommodation that while she exercised the royal prerogative on matters of state, he ruled the royal roost when it came to domestic affairs. Or as one wit suggested: Elizabeth wore the crown and Philip the trousers.

He tried to ignore the slights of patronizing courtiers and functionaries, but there was one issue that infuriated him: His children carried the family name Windsor and not Mountbatten. He once said, “I am nothing but a bloody amoeba. I am the only man in the country not allowed to give his name to his own children.”

Although he always took an official back seat, the Queen did her best to include him on ceremonial occasions. “My husband and I,” was such a frequent opening in her speeches that it became a parody. Knowing her husband’s frustration that none of his children carried his (adopted) name, she declared in 1960, that her descendants (other than her own titled children who carry the HRH designation) would henceforth carry the name Mountbatten-Windsor.

They celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary in November, 2007. “He has, quite simply, been my strength and stay all these years,” she said in a public tribute. To which Philip replied: “Tolerance is the one essential ingredient of any happy marriage. You can take it from me that the Queen has the quality of tolerance in abundance.”

From left: Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall; Prince Charles, Prince of Wales; the Queen; Prince Philip; William Duke of Cambridge; and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, at Buckingham Palace on Dec. 8, 2016.DOMINIC LIPINSKI/AFP/Getty Images

Final years

Well into his late 80s, he carried out more than 300 engagements a year and was said to have the energy and fitness of a man half his age. After celebrating his 90th birthday in June, 2011, six weeks after his grandson Prince William had married commoner Kate, Duchess of Cambridge, in a globally televised ceremony at Westminster Abbey, he announced he had “done [his] bit” and was going to slow down and reduce his public activities.

He suffered chest pains two days before Christmas that year and was taken to hospital, where he underwent a coronary angioplasty and had a stent inserted. He was hospitalized again in June, 2012, for a bladder infection, after standing the day before on an open barge in filthy weather on the Thames to launch celebrations of the Queen’s diamond jubilee. As resolute as ever, the Queen appeared without her consort at the celebrity-studded concert on a stage in front of Buckingham Palace that evening.

Prince Charles led the thousands of spectators in three cheers for his father’s quick recovery and the crowd responded with roaring enthusiasm. The monarch was alone again the next morning at a special Thanksgiving service at St. Paul’s Cathedral, but Philip was soon back at her side, frail but resilient.

He carried on for nearly a decade, having a hip replacement in 2018 and finally, at 97, giving up his driver’s licence after a car accident in 2019, in which the driver of the other car suffered a broken wrist.

In the past few years, many of his official duties were assumed by other senior members of the Royal Family, especially Charles, the heir presumptive, and his true love, Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall. Once scorned as the other woman in Charles’s marriage to Diana, Camilla gradually became accepted, even welcomed, by the public after her quiet wedding to Charles in 2005.

Prince William and his wife, Kate, the Duchess of Cambridge, assumed more and more royal duties, especially after Philip’s second son, the scandal-plagued Prince Andrew, the Duke of York, retreated from public life in 2019 because of his friendship with convicted sexual abuser and accused sex trafficker, the late Jeffrey Epstein.

Prince Philip and the Queen are introduced to their new great-grandson, Archie, by Prince Harry, Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, and her mother Doria Ragland, in 2019.Chris Allerton/SussexRoyal via AP

The Royal Family was rocked by the defection of Prince Harry the following year, a rupture that Philip felt keenly as he had become very close to his grandson after Diana’s death in August, 1997. “Philip welcomed Meghan at the beginning, he knows what it’s like to be an outsider,” Seward, Philip’s biographer, told Vanity Fair in 2020, ”but their actions have left a bad taste and as a consequence the relationship with Harry has suffered.”

The pandemic caused a major retreat from public life for both the Queen and Philip. As the coronavirus surged, they moved from Buckingham Palace to Windsor Castle, where they were photographed quietly celebrating their 73rd wedding anniversary in November, 2020. They remained healthy in their isolation and like other nonagenarians in Britain were vaccinated against the virus earlier this year.

Although he was not infected with COVID-19, Philip was hospitalized “as a precaution” on Feb. 17. The Queen remained at Windsor Castle, his absence a harbinger of her life to come without the steadfast presence of the husband who had been her “liege man of life and limb.”

Prince Philip in Canada: A visual guide

Aug. 4, 1954: Prince Philip casts a critical eye over RCAF cadets at the Royal Canadian School of Military Engineering at Sardis, B.C.The Canadian Press

June 30, 1959: Prince Philip is installed as president of the Canadian Medical Association at their annual meeting in Toronto’s Royal York Hotel.Harold Robinson/The Globe and Mail

Nov. 7, 1967 (left): Prince Philip wings his way into Toronto at the controls of a Royal Air Force twin turboprop Andover transport. July 1, 1967 (right): Prince Philip and the Queen arrive on Parliament Hill in Ottawa for the morning ecumenical service on Canada’s 100th birthday.Harold Robinson and John McNeill/The Globe and Mail

Aug. 1, 1973: Prince Philip and Margaret Trudeau, prime minister Pierre Trudeau’s wife, listen to the Queen during a ceremony opening Ottawa’s Lester B. Pearson Building, the new home of the foreign affairs department.John McNeill/The Globe and Mail

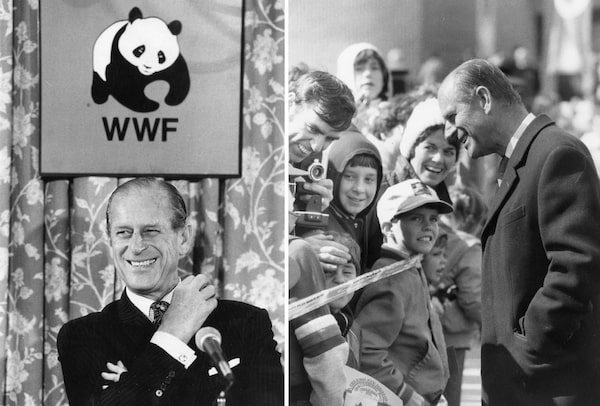

Nov. 9, 1982 (left): Prince Philip attends a press conference for the World Wildlife Fund of Canada at the King Edward Hotel. Sept. 27, 1984 (right): Prince Philip stops to chat with children in Toronto on his tour of Ontario.Tibor Kolley/The Globe and Mail

March 14, 1989: At North York City Hall, Prince Philip speaks with Ontario lieutenant-governor Lincoln Alexander, along with mayor Mel Lastman, second from left, and his wife, Marilyn.James Lewcun/The Globe and Mail

May 25, 2005: The Queen and Prince Philip watch performers wearing cowboy hats at their official departure ceremony at Calgary’s Saddledome. Behind the Duke of Edinburgh are then-governor-general Adrienne Clarkson and her husband, John Ralston Saul.Paul Chiasson/The Canadian Press

April 27, 2013: Prince Philip chats with members of 3rd Battalion of The Royal Canadian Regiment at Queen’s Park in Toronto. The two-day Canadian trip would be his last official visit to the country.Fred Thornhill/Reuters