Flower petals, thrown in tribute by supporters, cover Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's car on Sept. 13 as he leaves the New Delhi headquarters of his Bharatiya Janata Party, which celebrated his recent completion of the G20 summit.The Associated Press

In February, 2019, residents of Balakot, a small town near the de facto border between India and Pakistan in the disputed region of Kashmir, were awoken by loud explosions. Indian air force jets had bombed what they said was a training camp for terrorists who carried out a deadly suicide attack in Indian territory a week earlier.

While Pakistan disputed both the target and effectiveness of the strikes, Indian politicians and media hailed the operation, with Amit Shah, then president of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), saying it showed “the will and resolve of a new India.”

Speaking the following month, Prime Minister Narendra Modi promised his military would “barge into the homes of terrorists and kill them,” vowing to hunt down those who threatened Indians’ safety “even if they hide in the bowels of the earth.”

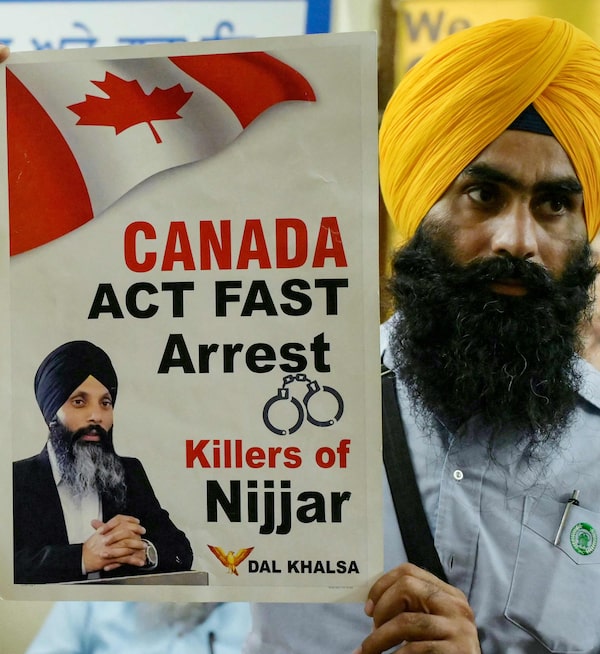

A member of a Sikh organization in Amritsar, India, protests on Sept. 22 with a poster of slain separatist leader Hardeep Singh Nijjar.NARINDER NANU/AFP via Getty Images

It was a dramatic statement of intent, one that has echoes today, as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said on Monday that Canadian authorities have credible intelligence that the mid-June murder of Sikh separatist leader Hardeep Singh Nijjar in Surrey, B.C., can be linked to Indian government agents. Since that announcement, the two countries have expelled each others’ diplomats and India has suspended all visa services for Canadians.

India has vehemently denied any involvement, and so far, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has refused to make public what evidence the government has. But if the accusations are proven, they would not be completely out of keeping with an India that has become not just more assertive on the global stage under Mr. Modi, but at times swaggering: New Delhi has defied Western pressure to break with Russia, stared down China in a territorial dispute in the Himalayas, and worked to marginalize arch-rival Pakistan.

Such self-confidence is understandable: India is the fastest growing economy in the world, has overtaken China as the most populous country, and recently became only the fourth nation to successfully land on the moon. India’s importance as both a potential geopolitical counterweight to Beijing and a major new driver of the global economy was on display this month at the G20 summit in New Delhi, where Western leaders tripped over each other to praise Mr. Modi – with the notable exception of Mr. Trudeau, whose own tense exchange with the Indian Prime Minister offered a preview of the soon-to-unfold crisis.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau leaves a photo op with Mr. Modi on Sept. 9 at the G20 summit.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

So far, Ottawa’s allies have shown no signs of breaking with India or the type of concerted response seen after Moscow attempted to kill former spy Sergey Skripal in the U.K. in 2018, when more than 150 Russian diplomats were expelled by various countries in solidarity with London. Even if Mr. Trudeau can present evidence of New Delhi’s complicity, few in India expect a major downturn in relations, such is their country’s importance in the the current geopolitical climate.

Nor will Mr. Modi face any backlash back home, where he has long cultivated an image as a Hindu strongman, reasserting India’s global role after centuries of dominance by first Muslim rulers and then the British. Even after almost a decade in power, a growing authoritarian streak, and several major policy missteps – including a disastrous currency devaluation and proposed agricultural reforms that led to widespread protests before being dropped – Mr. Modi’s party remains the firm favourite to win next year’s general election, which both he and the opposition are framing as a referendum on his time in office.

“He’s at the height of his popularity within India,” said Harsh Pant, vice-president of the Observer Research Foundation, a New Delhi think tank. “The support for him is quite extraordinary.”

Opposition parties have come together in a broad alliance encompassing 28 political parties spanning the far-left to centre-right, with the sole focus of turfing the BJP out. Some fear this could be their last chance to do so, said Shashi Tharoor, a senior member of the Congress party, which dominated Indian politics before the rise of Mr. Modi’s BJP. “The perception is that if this government comes back to power a third time, it might be a point of no return for the democratic India we all cherish,” Mr. Tharoor told The Globe and Mail.

Police detain supporters of the opposition Congress party at an anti-Modi protest in New Delhi on Aug. 8. The party and 27 others are part of a broad alliance hoping to unseat Mr. Modi in elections next year.Altaf Qadri/The Associated Press

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/5OLEHTMKSFL4POC627ZW7D3TDM.JPG)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/J7SWSAXNNBALXLA7L7IUJF6ABI.jpg)

Narendra Modi grew up poor in Vadnagar, in the western state of Gujarat, a member of what the Indian government terms “backward classes,” lower castes which have typically been disadvantaged or marginalized.

As a young man, Mr. Modi joined the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the far-right Hindu nationalist group and ideological wellspring of the BJP. In the 1980s, Mr. Modi took on the first of a number of increasingly senior organizational roles at both the local and national levels, eventually becoming Chief Minister of Gujarat in 2002.

Soon after he got the job, the state devolved into communal riots, after Muslims were blamed for the death of dozens of Hindu pilgrims in a train fire. At least 1,000 people were killed in the subsequent violence, the vast majority of them Muslim, and there were claims of police and government inaction, or even complicity. While Mr. Modi was officially cleared by the Supreme Court of India in 2012, the incident resulted in him being barred from many Western countries, including Canada and the United States, something that remained the case until shortly before his election as prime minister years later.

First responders try to douse a burning train in Godhra, Gujarat, in 2002. Fifty-nine Hindu passengers died in the fire, which set off a wave of anti-Muslim violence.The Associated Press

In a leaked U.S. government cable from 2006, written as it became clear Mr. Modi was a potential future national leader, Michael Owen, the then-U.S. consul general in Mumbai, said Mr. Modi had “successfully branded himself as a non-corrupt, effective administrator, as a facilitator of business in a state with a deep commercial culture, and as a no-nonsense, law-and-order politician who looks after the interests of the Hindu majority.”

“In public appearances, Modi can be charming and likeable. By all accounts, however, he is an insular, distrustful person who rules with a small group of advisors,” Mr. Owen wrote. “He reigns more by fear and intimidation than by inclusiveness and consensus, and is rude, condescending and often derogatory to even high level party officials.”

In later cables, diplomats wondered at Mr. Modi’s ability to manage the type of unsteady coalitions that had ruled India for several administrations at that point, a dilemma he dodged by the BJP winning the most decisive victory for any party in more than two decades. The result was driven in part by widespread frustration at corruption scandals and inaction that had characterized the previous government, led by Congress, but also Mr. Modi’s own growing popularity and an aspirational, self-confident and religiously tinged message that resonated in particular with many Hindus, even as it sparked fear among Muslims and other minorities.

Newly elected lawmakers raise their hands at India's parliament in 2019 to support Mr. Modi's selection as their new leader.Manish Swarup/The Associated Press

As he had in Gujarat, Mr. Modi embraced businesses and cut red tape. In the past decade, India’s economy has expanded at an average rate of around 5-per-cent year-on-year, while the number of people living in extreme poverty has halved. The Indian middle class has exploded, and Indian companies have become major global players. With the slowdown of the Chinese economy – in part owing to the COVID-19 pandemic – and a push toward de-risking by many countries fearful of Beijing’s influence, India appears poised to be a major beneficiary, particularly when it comes to manufacturing.

In elections in 2019, the BJP won almost 38 per cent of the vote, growing its majority to 303 of the 545-member lower house. Congress only took 52 seats, with no party large enough to be designated the official opposition.

Prof. Pant said Mr. Modi has “been able to continuously generate support for himself beyond the confines of traditional BJP voters.” Partly this was down to the Prime Minister’s personal charisma, he added, “but he’s also very politically intuitive, in terms of reaching out to the lower strata of Indian society and showcasing delivery.”

This has included not just traditional prestige projects like the opening of a new parliament building – which Mr. Modi oversaw this month – but also tangible benefits like a drive to build more than 110 million toilets around the country and end open defecation, the type of issue that affects many people’s lives but is not usually discussed by senior officials.

Mr. Tharoor, the opposition politician, said it was undeniable Mr. Modi is a gifted orator and “brilliant at the public-relations aspect of his job.”

“He uses the bully pulpit as nobody since Theodore Roosevelt has,” he said. “And he manages to market every accomplishment – even if that often merely involves the relabelling of previous government programs – as if it was something wholly new that he’s dreamed up to transform the lives of ordinary Indians.”

A worker clears debris at a restaurant near Nuh this past Aug. 1 after it was partly vandalized during sectarian clashes. Nuh, the only Muslim-majority district in the northern state of Haryana, erupted into violence during a Hindu procession through the area.Altaf Qadri/The Associated Press

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/DQIP3JSWDVLVRDGH35W3ZHFCR4.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/BJ4LXM2RZ5PT5K7QEWEMN7J6ZM.JPG)

For both supporters and critics of Mr. Modi, one project has been symbolic of how he has put Hinduism at the forefront of Indian politics – often for his own gain and at the expense of wider interreligious harmony. Just as the next election campaign kicks into high gear in January, Mr. Modi will finally deliver on a decade-old promise to open a Hindu temple in the key campaign state of Uttar Pradesh, on the site of a mosque destroyed by rioters in 1992.

Both the RSS and BJP are adherents of Hindutva, an ideology that at its most extreme calls for India to become an explicitly Hindu country, not the secular state envisioned by its founders. As home to 200 million Muslims, more than any country but Indonesia, as well as substantial Sikh and Christian communities, the growing influence of Hindutva in India has left many worried, particularly as it has coincided with a rise in violence against minorities. In recent years, mosques have been vandalized, imams shot and stabbed, and ordinary Muslims lynched in the street.

“The government has otherized a vast portion of the population, and made acceptable a level of public bigotry that as a child growing up in India I never would have thought possible even behind closed doors,” said Mr. Tharoor.

In a shocking incident this July, a railway police officer shot dead four people on a train in Maharashtra, the central Indian state which encompasses Mumbai. According to local media, Chetan Singh sought out Muslims on the train to kill. A video showed him holding a gun and standing over a body, telling other passengers that “they operate from Pakistan, this is what the media of the country is showing.” He says people should vote for “Modi and Yogi,” an apparent reference to Yogi Adityanath, the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh and senior BJP figure, who is known for anti-Muslim policies and dog-whistle comments.

Media members rally in 2019 to oppose the arrest of journalists for their social-media posts about Uttar Pradesh politician Yogi Adityanath.Anushree Fadnavis/Reuters

Indian institutions have proved unable or unwilling to rein in the growing violence, or the country’s authoritarian slide, as New Delhi has cracked down on independent media and civil society groups. In a ranking by Freedom House, a Washington-based think tank that rates civil liberties in countries around the world out of 100, India has dropped more than 10 points in the past five years, and is classed as only “partly free.” The Sweden-based V-Dem Institute classifies India as an “electoral autocracy.”

Mr. Trudeau and other Canadian politicians have expressed concerns about shrinking civil society in India and the government’s treatment of Muslims and Sikhs. This did not stop Ottawa pursuing a new trade deal with New Delhi before the latest spat plunged relations into a deep freeze, and other Western countries have been similarly unwilling to break with India over human-rights issues.

It is no surprise then, that many of Canada’s allies would be unwilling to take a stand in relation to Mr. Trudeau’s recent allegations, Saira Bano, assistant professor in political science at Thompson Rivers University, wrote this month. ”India is simply too important for strategic and economic reasons.”

An annual report on India published in March by the U.S. State Department noted “significant human rights issues” including “extrajudicial killings by the government or its agents,” arbitrary arrests, “restrictions on freedom of expression and media” and a “lack of accountability for official misconduct” at all levels of government. Months later, Mr. Modi enjoyed a rapturous reception in Washington, addressing a joint session of Congress where he received multiple standing ovations.

Mr. Modi prays with the presidents of France, Indonesia, Brazil and the United States in a Sept. 10 service at New Delhi's Mahatma Gandhi memorial on the sidelines of the G20 summit.PIB/AFP via Getty Images

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/Y3EEKW6TAZJX5C74DQIZCBWFNM.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/IHPKLNV6WBPWXIIM7QLWRF3MEI.jpg)

Part of the calculus when it comes to criticizing Mr. Modi is that he is likely to be in power for the foreseeable future, despite the latest push by the opposition to unite and defeat him.

The Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), as the coalition is known, hopes by focusing opposition support around a single candidate in each seat, it can undo benefits the BJP has gained from India’s first-past-the-post system and avoid fracturing the anti-Modi vote.

There is some evidence the threat has gotten under Mr. Modi’s skin: Since the coalition adopted the INDIA moniker, the Prime Minister and other BJP figures have begun to promote use of India’s official non-English name, Bharat. But it remains to be seen whether the alliance can unite around a coherent platform and hold together long enough to defeat the BJP.

Some critics of Mr. Modi have also expressed concern a single defeat might not be enough: After Indira Gandhi’s Congress lost to an alliance of parties in 1977 urging voters to choose between “democracy and dictatorship,” the coalition struggled to rule and soon split, and Ms. Gandhi returned to power with a larger majority in 1980. Mr. Tharoor said he understood such concerns but pointed to the longer terms of other coalition governments, including that which preceded Mr. Modi’s, under Congress prime minister Manmohan Singh.

Both sides are presenting the coming election as a referendum on Mr. Modi, who has demonstrated his political adroitness in recent months, using events such as the G20, the opening of the new parliament building and India’s recent moon landing to further boost support for the BJP. In the past decade, India has regained its position as a major world power, and seems poised to only become more influential in the coming years. That this would have happened with or without Mr. Modi is probably the case, but he seems to be gambling on the fact many Indians may not be so sure.

“For a long time in world history, India was one of the top economies of the world. Later, due to the impact of colonization of various kinds, our global footprint was reduced,” Mr. Modi said in a rare interview with Indian media this month. “But now, India is again on the rise.”

India and Canada: More from The Globe and Mail

How have people in India responded to the Trudeau government’s explosive allegations about the killing of a Sikh activist in B.C.? From New Delhi, Asia correspondent James Griffiths spoke with The Decibel about the latest developments. Subscribe for more episodes.

Explainers

What is the Khalistan movement, and how was Hardeep Singh Nijjar involved?

The killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar: A timeline of events

India has suspended all visa applications for Canadians. Here’s what that means for travel

Commentary

Omer Aziz: The real reasons Canada’s relationship with India is broken

Justin Trudeau brings Canada’s ties with India under increasing strain