Ruling party candidate Claudia Sheinbaum kicked off her presidential campaign last week with a massive rally in central Mexico City and promises of continuity, pledging to deepen the populist project of her predecessor and mentor, outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Her main opponent, Xóchitl Gálvez, standard bearer for a three-party coalition, started her campaign with a midnight vigil in one of Mexico’s most violent municipalities, where she promised to build a mega-prison and offer “no more hugs for criminals” – a reference to the President’s security strategy of “hugs, not bullets.” But, like Ms. Sheinbaum, she vowed to continue with Mr. López Obrador’s popular social programs, signing a pledge in blood to prove her point.

Mexico’s June 2 elections will showcase the country’s social progress: The two main electoral coalitions have nominated female candidates, meaning the traditionally macho country is likely to pick its first female president. But the race will show the rough realities of modern Mexico, too, as the contest unfolds against a backdrop of deep political divisions and rising violence – with drug cartels meddling in local and state elections and killing candidates with impunity.

There are fears also from civil-society organizations of democratic backsliding under Mr. López Obrador, who rails against the country’s Supreme Court and continues to attack the country’s electoral institute and autonomous agencies. His ruling Morena party, meanwhile, risks turning into a revamped version of the old Institutional Revolutionary Party, which governed Mexico for 71 years under an authoritarian system of top-down presidential leadership.

“The big choice is going to be between democracy and authoritarianism,” said Roger Bartra, a professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Claudia Sheinbaum and Xóchitl Gálvez are presidential candidates for the Morena and Broad Front for Mexico blocs, respectively.Jaime Lopez/Getty Images; ULISES RUIZ/AFP via Getty Images

Ms. Sheinbaum, a climate scientist and former mayor of Mexico City, leads all polls and would become the first Jewish president in what remains a heavily Catholic country. She identifies as left-leaning but leads a big-tent coalition encompassing everyone from progressives to evangelicals.

Ms. Gálvez, a senator and businesswoman, rose from an impoverished Indigenous village to study computer engineering and become a successful tech entrepreneur. She voiced progressive views upon winning the nomination but turned more to the centre after getting scorn from parts of her coalition, which spans the political spectrum.

Jorge Álvarez Máynez, a politician with the small Citizen Movement party, rounds out the field of presidential hopefuls and has attempted to claim the middle ground between his rivals.

Yet, for all the historical importance of likely electing the country’s first female president, much of the focus remains on Mr. López Obrador, who is constitutionally prohibited from seeking a second term.

The success of women’s political participation is “being overshadowed by the polarization dynamics of López Obrador,” said Raúl Zepeda Gil, a Mexican lecturer in development studies at Oxford University. “The problem of having a polarized society is that we cannot see beyond López Obrador.”

Critics of Mr. López Obrador and Ms. Sheinbaum, shown in stuffie form at her Mexico City campaign rally on March 1, say he is trying to influence how she would govern if elected.Aurea de Rosario/The Associated Press

Ms. Sheinbaum and Mr. López Obrador attend a ceremony in 2018, when they were mayoral and presidential candidates, respectively. Both offices come with one-term limits of six years.Ginnette Riquelme/Reuters

Analysts expect Mr. López Obrador – or AMLO, as he is known – to try intervening in the presidential campaign and influencing a future Sheinbaum administration, should she win.

The President introduced a package of constitutional reforms on Feb. 5, which included putting Supreme Court nominees and all judges to popular election, assigning the military control of public security and eliminating the transparency institute (Mexico’s freedom of information body), which Mr. López Obrador derides as a waste of money. The reforms have little chance of clearing Congress before the elections. But analysts say the President has presented them to wrong-foot the opposition. The reforms also double as Ms. Sheinbaum’s campaign platform.

“He’s doing this to keep dominating the agenda, knowing he’s going to lose, because his discourse, his image and his narrative is that of a well-intentioned person” being thwarted by the old elites, said Fernando Dworak, a political analyst in Mexico City.

In mid-February, 90,000 protesters crammed into the Zócalo – the main square in central Mexico City – to express opposition to the President’s proposed reforms. Mr. López Obrador responded by erecting barricades around the National Palace and lowering the massive Mexican flag flying over the iconic plaza. “The message is: ‘The Mexican people are the ones with me; the ones who are marching are not the people,’ ” historian Enrique Krauze said of the President’s refusal to fly the flag over a civil-society protest.

Supporters of Mr. López Obrador blast the notion of democratic decline in Mexico. They point to the march happening without incident and the President’s decision to respect the constitution by not running for re-election. “Democracy in Mexico is not at risk,” said Diana Alarcón, a spokesperson for Ms. Sheinbaum. She gave the example of Mexico City, where Morena lost half of the 16 borough governments in 2021 “with Claudia Sheinbaum as mayor,” as proof of opposition politics thriving.

For his part, Mr. López Obrador accused the demonstrators of “coming out to defend their democracy, that of the oligarchs, of the rich, the democracy of the corrupt.”

The response was a vintage move for the President. He has led a popular and populist administration since winning a landslide election on an anti-corruption platform and pledges to chasten elites and “put the poor first.”

Supporters say he’s delivered. He nearly tripled the minimum wage, didn’t raise taxes and initiated a program of cash stipends for seniors, students and single mothers. The peso strengthened under his watch – though mostly owing to external factors, according to economists – while remittances sent home by Mexicans abroad rose sharply.

Poverty dropped by nearly six percentage points between 2018 and 2022, according to the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) – something the President takes credit for. Economists, however, are more circumspect, and say a 25-per-cent increase in social spending prior to the elections will leave a large budget deficit for his successor.

“The proportion of family income coming from work has dropped since 2018,” said Gabriela Siller, head of financial and economic research at Banco Base. “Mexican households increasingly depend on remittances and money the government gives them.”

Mr. López Obrador initially pursued austerity policies, too, spending just 1 per cent of GDP on pandemic relief. He scrapped a government health insurance scheme, which has left nearly 40 per cent of the population without access to health care, according to CONEVAL. He prioritized the construction of megaprojects such as airports, railways and refineries, while pumping money into the dilapidated state-run oil company Pemex. Violence continues convulsing swaths of the country, though Mr. López Obrador boasts the homicide rate fell by 20 per cent.

“He’s incompetent. He has an incompetent government; they haven’t accomplished anything,” said Federico Estévez, a political science professor at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico. “But he isn’t blamed for anything either.”

Mr. López Obrador sits at the National Palace reading his latest book, ¡Gracias!, in which he disparages Ms. Gálvez, calling her a 'classist.'Mexico Presidency via REUTERS

Analysts attribute Mr. López Obrador’s ability to escape blame to a daily morning news conference that can drag on for more than three hours. It sets the day’s news cycle while trolling opponents, rallying supporters and relitigating the past.

“The President’s comments stick,” Prof. Estévez said. “People don’t quite know the ins and outs of the disputes, but they like the President’s response to whatever it is.”

María Elena Morales, 60, cleans houses for a living in Mexico City and confesses to not following politics closely. But she appreciates the 6,000-peso stipend ($460) her elderly mother receives every two months and knows the President’s narrative on where the money comes from.

Politicians previously “made off with the money and he’s giving it to us,” she said.

Both Ms. Sheinbaum and Ms. Gálvez promise to continue with the President’s cash stipend schemes.

Ms. Sheinbaum is a familiar face in the municipal politics of Mexico City, where she kicked off her campaign on March 1. When Mr. López Obrador was mayor in the 2000s, Ms. Sheinbaum, an expert on energy policy, became his environment chief, and she would be elected mayor in 2018.Luis Cortes/Reuters

A poll released March 1 by the newspaper El Financiero gives Ms. Sheinbaum a 17-point advantage over Ms. Gálvez.

Ms. Sheinbaum, 61, started as a student activist. She earned a PhD in environmental engineering and entered politics as environment secretary in Mr. López Obrador’s 2000 to 2005 Mexico City government, where she oversaw the construction of elevated freeways.

She became a borough chief in 2015 and Mexico City mayor in 2018. Ms. Sheinbaum speaks of accomplishments while mayor such as carrying out a competent pandemic vaccination program, reducing high-impact crimes and expanding public transportation – though the 2021 crash of an elevated metro line, causing 26 deaths, haunted her administration.

“There are signs they have been more methodical about approaching insecurity in the city,” said Falko Ernst, senior Mexico analyst for the International Crisis Group. He described her security team as “experienced” and “technocratic,” but facing “political challenges” if promoted to the national level.

But analysts say her political career has been tied to Mr. López Obrador since the start, and her refusal to voice differences with him sent large swaths of the national capital – long a bastion of the left – to the opposition in the 2021 midterms.

“I’m desperate to know who the real Claudia is,” said Alex González Ormerod, editor-in-chief of Whitepaper, a business publication. “But we won’t know it until she’s sitting in that chair … and can exert power for the first time.”

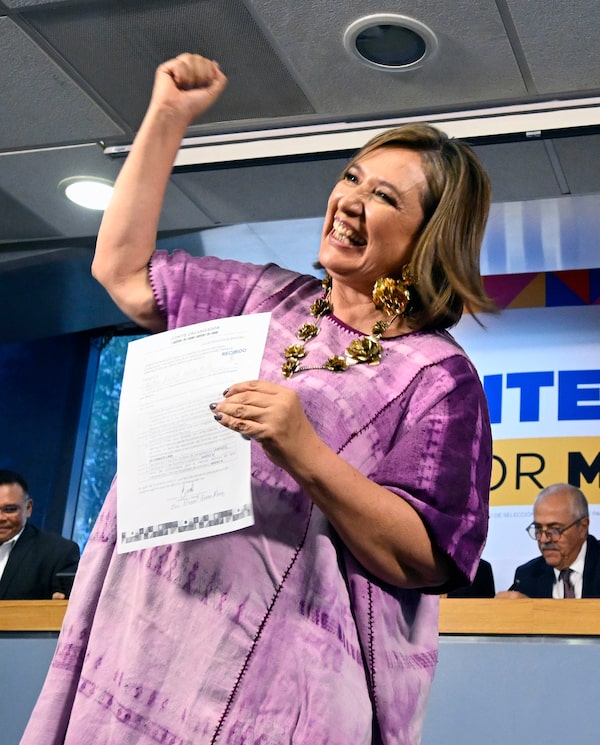

Ms. Gálvez celebrates after pre-registering to run for the presidency last June.ALFREDO ESTRELLA/AFP via Getty Images

Ms. Gálvez, 61, grew up far from power and privilege as the daughter of an Otomi schoolteacher. She sold tamales and gelatin desserts as a child but won a scholarship to the National Autonomous University of Mexico and founded a tech firm. She was headhunted by then-president Vicente Fox’s administration in 2000 to head the Indigenous affairs commission and later served as a borough chief in Mexico City and a senator.

Famous for riding a bicycle and often seen wearing traditional embroidered blouses known as huipiles, Ms. Gálvez planned to run for mayor of Mexico City but rose to prominence with a political stunt: She won an injunction giving her the right of response to accusations from Mr. López Obrador at his morning news conference. The photo op of her knocking on the door of the National Palace without answer went viral.

Mr. López Obrador promptly greeted her candidacy with attacks, casting aspersions on her up-from-the bootstraps biography. He also insinuated corruption – a common accusation accompanying success in Mexico – by displaying her company’s contracts with the government at his daily news conference. Quick-witted and salty tongued, Ms. Gálvez retorted, “My business is so awesome that even your government has hired it.”

A Gálvez supporter brings a knitted likeness of her to a March 1 rally in Fresnillo, Zacatecas state.ULISES RUIZ/AFP via Getty Images

Her story of personal success plays well among those in the upper middle classes, who Mr. López Obrador has derided as “snobs.” But she floundered at times during the precampaign period and lacked a coherent message. The three parties in her coalition only joined forces after being annihilated in 2018.

“The opposition still doesn’t know what happened in 2018,” said Mr. Dworak, the political analyst. “Xóchitl was the most competitive candidate” for the opposition, “even knowing she wasn’t that competitive.”

Should Ms. Sheinbaum or Ms. Gálvez capture the presidency, they would join women already heading up the Supreme Court and both houses of Congress.

The country has had several female presidential candidates over the decades. But the emergence of two female front runners didn’t happen by accident. Analysts credit a political reform requiring gender parity in political nominations.

“It helped normalize the idea of women in decision-making positions,” said Bárbara González a political commentator and host of the podcast Las Insumisas.

Analysts also point to a burgeoning feminist movement, whose leaders have advocated for issues such as abortion decriminalization – achieving it on the national level in 2023 – along with increased women’s political participation. They also demanded government action on gender violence, an issue still pending in a country where 10 women a day are murdered.

“Claudia and Xóchitl owe the feminist movement their candidacies,” said Maricruz Ocampo, an activist who was among the women pushing for gender parity rules. “If any woman with a successful political career thinks she made it on her own she’s delusional.”