A guard keeps watch at a public security office in Hanoi, capital of Vietnam. Arrests, surveillance and censorship of dissidents are widespread in this Southeast Asian country.Photography by James Griffiths/The Globe and Mail

On a Thursday night in late March, dozens of Canadian diplomats, trade officials and local support staff posed on the steps of Vietnam’s Independence Palace, in the heart of Ho Chi Minh City. In a giddy mood at the climax of a successful trade mission, they sang a few bars of the Canadian national anthem while waiting for the photographers to set up.

But if the visitors had reason to be pleased, so did their hosts: Canada is only the latest country to send a high-profile delegation to Vietnam seeking closer ties with the Communist-ruled state, whose economy is expected to be among the fastest growing in the world this year.

In recent years, as it signed a free-trade deal with the European Union, joined the Comprehensive and Progressive agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and upgraded diplomatic relations with both the United States and Australia, Vietnam has talked about opening up politically as well as economically.

Canadian Trade Minister Mary Ng, middle, attends talks in Hanoi last month with her deputy Rob Stewart, left, and ambassador Shawn Steil.

At the same time however, its leaders have taken steps to ensure this will never happen, jailing dissidents, cracking down on civil society and surveilling and muzzling critics online.

Western officials insist that in private, they hold Vietnam to its various commitments and push for reform, but publicly, Hanoi’s allies have said little and done less.

“It’s been decided by the West that we’re going to pursue closer diplomatic relations with Vietnam and that it’s in our interest to do so,” said Ben Swanton, co-director of Project88, which advocates for human rights in Vietnam. “And so we’re not going to take any actions that could be counterproductive to that goal.”

In the latest global Democracy Index put out by the Economist Intelligence Unit, Vietnam’s score was the third-lowest in Southeast Asia, behind only its Communist neighbour Laos and civil-war-wracked Myanmar. Worldwide, Vietnam ranked 136th in terms of democratic freedoms, down from a high of 128 in 2015.

Reporters Without Borders ranks Vietnam 178th out of 180 in terms of media freedoms, while an index from the European Union-funded Global State of Democracy Initiative shows protections for the rule of law and political participation essentially unchanged since the end of the Vietnam War in 1975.

According to Human Rights Watch, there are at least 163 political prisoners in Vietnam, including dozens of journalists. Three activists were jailed in the first two months of 2024 alone.

“They’re just wiping everything out,” Phil Robertson, HRW’s deputy Asia director, said of the Vietnamese authorities. “It’s scorched earth stuff.”

Ho Chi Minh City – seen from its tallest building, Landmark 81 – was once called Saigon, but in 1975 the victorious North Vietnamese renamed it after their founding revolutionary leader. The Communist state is still deeply concerned with protecting the party’s rule despite efforts to open up to the global economy.

Vietnam’s Foreign Ministry and embassy in Ottawa did not respond to a request for comment. In a submission to the United Nations, Hanoi said its “consistent policy is to protect and promote human rights” and this provides the foundation for Vietnam to “seriously undertake its international obligations and commitments.”

But in private, Vietnam’s leaders appear to feel otherwise. In February, Project88 published a leaked copy of a directive issued by the Politburo of the Communist Party of Vietnam, “on ensuring national security in the context of comprehensive and deep international integration.” Promulgated in secret in July, 2023, Directive 24 outlines a strategy for ensuring increased international engagement and economic openness does not threaten the political supremacy of the Communist Party.

With echoes of similar national security legislation in China, Directive 24 warns against external forces promoting “colour revolutions,” and instructs all levels of the party and government to “focus on developing and organizing the strict implementation of policies and laws on national security, especially in relation to international development cooperation projects, foreign investment, the activities of multinational corporations, [and] foreign non-governmental organizations in Vietnam.”

As Vietnam “implements international commitments,” the directive notes, officials should “proactively develop plans to prevent and control complicated situations relating to security and social order” and “ensure national security in all scenarios.” In apparent contradiction of commitments made both to the United Nations International Labour Organization and the European Union, it also calls for tight party control of nominally independent trade unions.

“Directive 24 is an all-out assault on the rights of Vietnam’s 100 million citizens,” Project88 said in a statement. “In issuing the directive, the country’s unelected leaders have made clear that Vietnam will not respect human rights, even as it deepens its integration with the world.”

Describing meetings with Western diplomats and EU officials since his organization published Directive 24 – the existence of which has been repeatedly referenced by top Vietnamese leaders, and in state media and government documents – Mr. Swanson said “the tenor of the conversation seems to be this is really bad, things are getting worse, but there’s nothing we can do about it.”

In Hanoi today, Vietnamese can see little of the reforms promised a decade ago by leaders who seemed willing to move past authoritarianism, as states such as South Korea and Taiwan did.

There was a moment when Vietnam did appear to be opening up, following the path of Taiwan and South Korea, both of which transitioned from authoritarianism in the 1980s and 1990s, rather than China, which has resisted pressure to reform and only strengthened one-party rule as its economy has grown.

As Nguyen Khac Giang and Dien Nguyen An Luong, analysts for the Singaporean think tank ISEAS, write in a paper on Vietnam’s political crackdown, in the 2010s there was a flowering of dissent online after repeated failed attempts to institute China-style internet controls.

Under the leadership of prime minister Nguyen Tan Dung, the government focused more on economic growth than political control, and Vietnam was also seeking greater engagement with the West, with paramount leader Nguyen Phu Trong meeting U.S. president Barack Obama in 2015.

Nguyen Phu Trong confers with Barack Obama in Hanoi in 2016, when the U.S. president reciprocated the Vietnamese leader's White House visit a year earlier.The Associated Press

In a rare interview with foreign media, Mr. Trong said Vietnam was willing to have “open and constructive dialogues” on issues such as “democracy, human rights and trade,” as it lobbied for membership in what was still then the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The following year however, Mr. Dung resigned and conservatives won out in an internal Communist Party power struggle, the ISEAS analysts write. Mr. Trong launched a sweeping anti-corruption campaign which continues to snare rivals to this day, and moved to “increase the Party’s control over the state and society.” New laws were passed targeting the internet, civil society and foreign NGOs.

With Mr. Obama’s successor Donald Trump scrapping the TPP, outside pressure on Hanoi to reform also quickly dissipated, Mr. Robertson said. “If you want to look at the direct damage on human rights in Southeast Asia from Donald Trump, Vietnam is example number 1.”

The presidents of the Philippines and Vietnam, Ferdinand Marcos and Vo Van Thuong, visit Hanoi's imperial citadel this past January. Their countries have roughly similar GDPs but very different roles in the geopolitical balance between China and the West.NHAC NGUYEN/AFP via Getty Images

The unwillingness to put pressure on Hanoi is not just about trade. Vietnam’s economy is growing rapidly but its GDP is roughly equivalent to that of other developing Southeast Asian Nations such as Malaysia and the Philippines and well behind Indonesia.

Where Vietnam’s importance comes in is with regard to China. Despite Hanoi’s long-standing close ties to its neighbour – which were upgraded to a strategic partnership months after a similar deal with the U.S. – Vietnam is seen in the West as vital for shifting supply chains away from China and pushing back against Beijing in the South China Sea, where the two Asian countries have competing territorial claims.

“Vietnam has become a lot more important in terms of geopolitical considerations,” Mr. Giang said in an interview. “Middle powers like Canada, Australia, Japan and South Korea also consider Vietnam a very important part of balancing risks in the current very uncertain geopolitical landscape in the Indo-Pacific.”

Asked by The Globe and Mail about U.S. engagement with Vietnam, Uzra Zeya, Under Secretary of State for Civilian Security, Democracy and Human Rights, said President Joe Biden’s administration had been “forthright in expressing our concerns with respect to issues like freedom of expression and religious freedom in Vietnam.”

“But our view is this engagement is part of our steadfast commitment, through diplomacy, to advancing a more free, open, secure and prosperous Indo-Pacific,” she added, using a phrase that is often seen as referring to Washington’s desire to contain China.

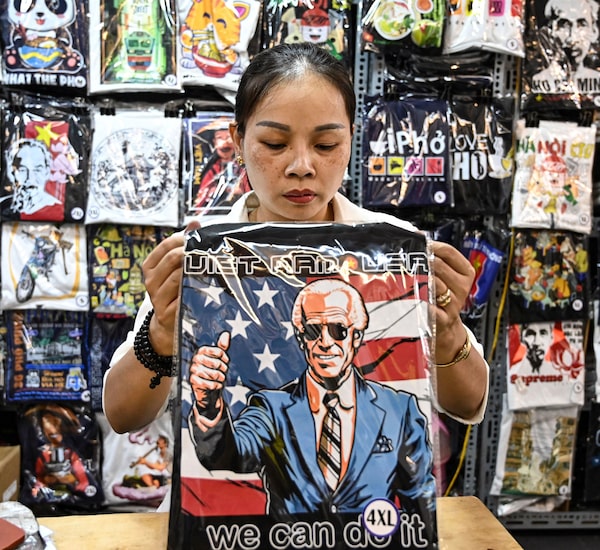

A Hanoi shop employee packs a Joe Biden T-shirt this past September, ahead of the U.S. President's visit to Vietnam.NHAC NGUYEN/AFP via Getty Images

For all its recent embrace by the West, however, there is little sign Hanoi feels pressure to take sides. As well as upgrading diplomatic relations with China, Vietnam is also a member of the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, an equivalent to the CPTPP, and President Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative.

Hanoi also retains close relations with Moscow, buying large amounts of Russian arms. In a phone call last month, Mr. Trong congratulated Russian President Vladimir Putin on his recent election victory – widely seen as unfair – and invited him to visit Vietnam later this year.

Mr. Robertson said that with the U.S. and EU not challenging Vietnam, there was little pressure on other countries such as Australia, Canada and Japan, all seeking closer relations with Hanoi, to do so either.

“Biden basically threw human rights in Vietnam under the bus and that’s what we’re seeing across the board,” he added.

In an interview in Ho Chi Minh City, Canadian Trade Minister Mary Ng said there was an expectation on her department “to lead with values that are important to Canada.” She pointed to forceful language in Ottawa’s Indo-Pacific Strategy on China, and the government’s response to India allegedly carrying out an extraterritorial killing on Canadian soil.

With regard to China, Ms. Ng said, Ottawa is willing “to challenge China in areas where Canadian values are important, such as in standing up for human rights or the rule of law.”

Asked whether a similar approach was taken with Vietnam, Ms. Ng said “when the occasion arises, we will do that,” adding the government can “do both things” when it comes to engaging economically and promoting human rights.

Ms. Ng, Canada's Trade Minister, embraces her Vietnamese counterpart, Nguyen Hong Dien.

Prior to landing in Vietnam, Ms. Ng had been in Malaysia. Other key Canadian trading partners in Asia include South Korea, where Ms. Ng is leading another delegation later this month, Japan and Indonesia.

All are democracies, but it was Vietnam that appeared to attract the most excitement, with hundreds of business delegates joining the trip, many of whom emphasized to The Globe not only the country’s economic potential but its political stability, something that can be hard to find in Southeast Asia but comes easier in a tightly controlled one-party state.

Multiple companies in the delegation were hoping to engage with Vietnam on environmental issues, as Hanoi seeks help in transitioning to a green economy. Ms. Ng also emphasized the work being done by Canada “in the space of tackling climate change and sustainability.”

Hanoi residents commute on a smoggy March day, a regular occurrence in a city whose air quality ranks among the worst in the world.NHAC NGUYEN/AFP via Getty Images

But on this issue, too, Vietnam has shown a willingness to say one thing and do another, with little apparent consequence.

In 2022, the G7 agreed to provide US$15.5-billion to Vietnam to help the country cut its reliance on coal. As part of that deal, Hanoi agreed “to ensure a broad social consensus” by regularly consulting with non-governmental organizations.

The assumption was this would include several environmental groups that played a key role in lobbying for the deal, known as the Just Energy Transition Partnership. But before the agreement came into force, Vietnam arrested multiple prominent activists, charging them with a variety of crimes including tax evasion and sending a chill throughout the environmental movement.

“These were the leaders of the climate change movement that made the deal possible in the first place by pushing the government to commit to a policy of net zero carbon emissions,” Mr. Swanton said.

Vietnam’s Foreign Ministry has denied these cases are politically motivated, saying the activists were “investigated, prosecuted and tried in accordance with the provisions of Vietnam law.”

Mr. Swanton said there has been little criticism of Vietnam over these arrests, other than from human rights NGOs and UN special rapporteurs, independent experts whose role is largely advisory. Nor have Western countries publicly responded to Directive 24 being leaked, with Australia and Canada both sending delegations to Hanoi soon after its publication.

“It seems it doesn’t matter how outrageous their practices or policies are,” he said. “The government of Vietnam has learned that they’re not going to face any repercussions.”

The Globe in Vietnam: More reading

Canada, the United States, Australia and China are keen to strengthen trade ties with Vietnam. Why, and why now? Foreign correspondent James Griffiths spoke with The Decibel about that after a trip to the Southeast Asian country. Subscribe for more episodes.

Eric Reguly: My journalist father’s Vietnam war story, revisited