Franio Domico Bailarin has been in hiding since September, when armed men came to his home in Colombia looking for him. 'We were supposed to be living happily,' he says of the 2016 deal between Colombia and the FARC militia. 'But that is not happening.'Yader Guzman/The Globe and Mail

Five years ago, in the ebullience of Colombia’s race toward peace, Franio Domico Bailarin returned home to the shores of the Rio Léon, the river in the country’s northeast where he and his indigenous ancestors had survived on iguanas, nutrias, lowland pacas, fish and jungle medicines.

But Mr. Domico is now a fugitive in his own country. He and his family went into hiding after a group of armed men came to their home on Sept. 23 and asked where he was. They wanted to do him harm, he believes, because his community’s land is coveted by a powerful cattle rancher. Drug runners also frequent the area.

At the time, Mr. Domico was away at a meeting. Warned of what happened, he has not returned since. Those still in the community, meanwhile, were told by the men that if they leave, “nosotros no respondamos,” or “we will not answer.” It was a threat of consequences if they do not comply – a pressure tactic to force the community to hand over its leadership. Unwilling to do so, they have remained in their homes, frightened to go elsewhere.

“We thought we would be able to live peacefully, sleep and be with our children and enjoy our territories,” Mr. Domico said, speaking from the relative safety of a hotel away from his home. “We were supposed to be living happily. But that is not happening.

“I’m tired. I’m devastated.”

Colombia's then-president, Juan Manuel Santos, shakes hands with FARC leader Timoleon Jimenez on Nov. 24, 2016, at the second signing of the peace deal.LUIS ROBAYO/AFP/Getty Images

Mr. Domico was not alone in envisioning a better life after the conclusion, in 2016, of a landmark peace accord that sought “an end, once and for all, to the historical cycles of violence” and earned former Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos the Nobel Peace Prize.

The deal put an end to over 50 years of armed conflict between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (better known by its Spanish initials, FARC), a left-wing guerrilla group. The two sides agreed on a raft of reforms, including a wave of land-title formalization to give small farmers legal ownership of their properties. The deal also called for a truth process, and an overhaul of the country’s political system to promote more participation by opposition parties. There was also to be an effort to reduce production of coca, the plant used to make cocaine, by helping farmers transition to other crops.

But five years after the signing of the accord, Colombians have been taking stock of what it has wrought. Although the violence once inflicted by FARC has ceased, other armed groups are now fraying the peace. Colombia’s rates of homicide and kidnapping remain well below the deadly heights they once occupied. But rates of mass killings – often an indication of paramilitary or narco-trafficker activity – are on the rise, as are the numbers of people who, like Mr. Domico, live in communities that have either been displaced or confined. Colombia now leads the world in the killing of environmental activists. Nearly 300 ex-FARC members have been killed.

It’s not a return to the worst of the country’s historical violence. “But the trends that we’re seeing right now are extremely worrisome,” said Renata Segura, deputy director for Latin America and the Caribbean at International Crisis Group, an organization that advocates for peaceful solutions. “We’re going from what was for the last few years very targeted attacks to really returning to massacres, attacks to the general population to control territory.”

The capture of the drug lord Otoniel in October has set the country further on edge. In some parts of Colombia, military officers were told to don civilian clothes when not at work, to avoid reprisals, while small settlements were placed under de facto curfews.

At top, police escort captured Gulf Clan leader Dairo Antonio Usuga David, alias Otoniel, through Bogota on Oct. 23. Five days later, at bottom, soldiers and peasants speak with members of the ombudsman's office in Tibu, a northeastern town near the Venezuelan border, as the soldiers – captured by locals for destroying coca plantations – were released.SCHNEYDER MENDOZA/AFP via Getty Images

Critics point to a litany of failures. For instance, though the peace agreement included a government pledge to formalize title to over seven million hectares of land, only one million hectares have been completed. “We actually committed to a target, which was to reduce rural poverty by 50 per cent over a period of 15 years. If you look at the figures, rural poverty has actually gotten worse – and this is prepandemic,” said Sergio Jaramillo, who was High Commissioner of Peace under Mr. Santos.

He faults the government of President Ivan Duque, which succeeded Mr. Santos’s administration in 2018, for being uninterested in the elements of the peace accord that sought to remake Colombia by easing the insecurities and penury that have long created fertile ground for violence. The accord contains 578 stipulations, but some 54 per cent of them have seen either minimal effort or no progress at all, the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at Notre Dame has tabulated. Some 28 per cent of the stipulations are considered complete.

Incomplete work in some areas has created new sets of problems. Take the push to wean farmers off coca. Some 99,000 families signed up. “Of these, only 55 per cent have received any help,” said Carlos Antonio Lozada, a former FARC commander who is now a senator. Many of the remainder now struggle to survive without a profitable narcotic crop or a suitable replacement. (A tonne of corn fetches roughly the same price as a pound of cocaine paste, the U.S. government estimates.)

In the meantime, the demobilization of FARC has left a vacuum of control that other armed groups have been quick to fill. “The Colombian state doesn’t have control of the land,” Mr. Lozada said. “The accord sought to ensure that the state could unify the country. But because the government didn’t want to approve implementation, the emptiness when FARC retreated was filled by other structures and organizations.”

Mr. Lozada is himself in many ways an embodiment of the tangible, if imperfect, change the peace accord has brought. He remains the subject of a U.S.$2.5-million reward from the U.S. Department of State, which says it wants information that could lead to his arrest or conviction.

But he is not hard to find. He occupies a large office in downtown Bogota. He wears a jacket and jeans and types on a MacBook while chatting about parenting and his adjustments to civilian life. “It’s a total change,” he said. He has no longing for his old life, though, and his criticism of the Duque government is leavened by faith in an accord he still sees as a tool “to change the country.”

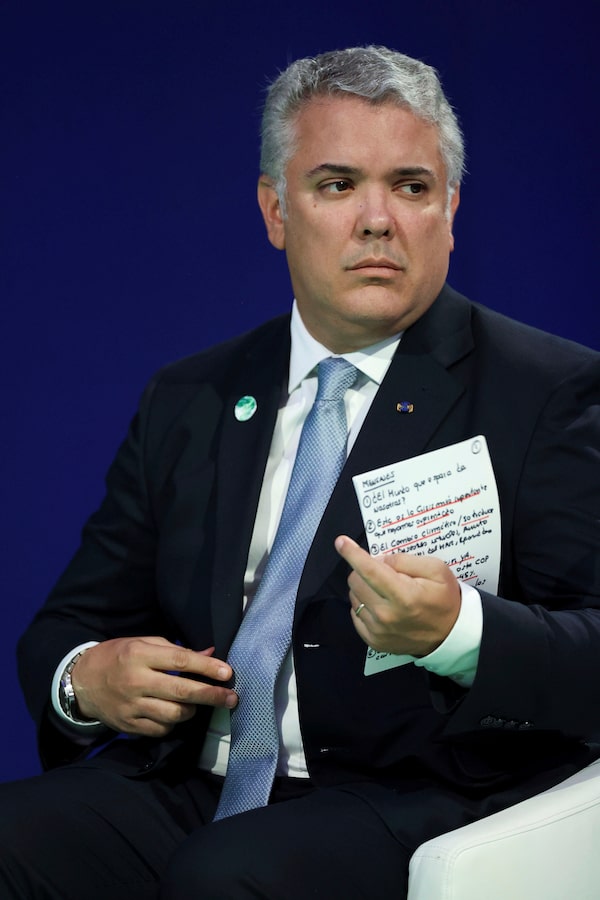

Colombian President Ivan Duque waits to speak at the COP26 conference on Nov. 2.Hannah McKay/Pool via AP

The Duque administration, meanwhile, has been eager to respond to critics. “What we have achieved is something that, from my perspective, is historical for Colombia,” said Emilio Archila, Colombia’s Presidential Counsellor for Stabilization.

The accord, Mr. Archila pointed out, envisions a 15-year timeframe. Only a third of that time has passed. And it’s unfair, he argued, to hold his government to account for a rise in violence tied to groups outside of FARC, when the accord was signed with FARC alone.

“The idea that by implementing the agreement by itself, just by that line, we would have achieved stable and permanent peace was nothing more than a headline,” he said.

Of the families that gave up growing coca, only 1 per cent have gone back to the crop, he said. Ex-FARC combatants have been killed, but the number each year is decreasing, and security services have saved the lives of twice as many ex-FARC members as have died, he said. A special investigative unit in the Attorney-General’s office has been particularly effective in prosecuting cases, with more than 150 sentences against those who have killed, and planned the killing of, ex-combatants.

“In every aspect of Colombian life, we are a much better country now than before we started the implementation,” he said.

Mr. Jaramillo, who is now a senior adviser at the European Institute of Peace, pointed to a feeling in Colombia “that you can actually move around more freely, and that your children are no longer at risk of being recruited to some armed group.”

A military helicopter flies near Necocli in northern Colombia on Oct. 24.DANIEL MUNOZ/AFP via Getty Images

But that feeling is not universal. Mr. Domico is not the only person from his hometown currently in hiding. Community leader Dilson Borja has also fled, after the armed men came searching for him, too. The Rio Leon is a key artery for the movement of drugs and weapons, Mr. Borja said. Violence caused the community to flee in 1996, before its return in 2016 amid the optimism surrounding the peace accord.

Police and the army have refused to assert control here, Mr. Borja said, and the community has been unable to gain title to its land, despite years of effort.

The country’s Congress has faulted the Duque administration for spending just 1.5 per cent of what is needed to support 170 communities in such rural development schemes, known by their Spanish acronym, PDET.

With the signing of the peace accord, “we had hope,” Mr. Borja said. But when the community has begged different levels of government for help – the Ministry of the Interior, the Indigenous Organization of Antioquia – “there has not been any answer,” he said.

So Mr. Borja is living on the run, while the people who were once his neighbours live in a kind of fear they thought was in the past.

“We cannot work. We cannot go out to the rivers. We cannot go to the town to buy some groceries,” Mr. Borja said. “That’s not freedom. That’s confinement.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Nathan VanderKlippe

Nathan VanderKlippe