An Israeli flag lies on Aug. 30 at the Munich memorial to the massacre at the 1972 Olympics. Eleven Israeli athletes died in the bloody conclusion to a hostage standoff with Palestinian extremists.Leonhard Simon/Getty Images

When Ankie Spitzer entered the bloodstained, ransacked apartment in the Olympic Village in Munich, she made a promise to herself to never stop talking about what she saw there. The day before – Sept. 5, 1972 – Israeli athletes and coaches had been attacked and held hostage by the Palestinian terrorist group Black September. It would end with Ms. Spitzer’s husband, fencing coach Andrei Spitzer, and 10 other Israelis dead.

What Ms. Spitzer didn’t expect was that her pledge would propel her into a 50-year fight – not with the terrorists who perpetrated the attack, but with German authorities.

Officials had failed to heed multiple warnings about a planned Palestinian assault at the Munich Olympics and mounted a disastrous police response once the terrorists struck. Five of the terrorists and German police officer Anton Fliegerbauer were also killed.

In the aftermath, German officials imposed a wall of silence. There was no public inquiry, no trial for the three surviving terrorists and the victims’ families were made to wait 20 years before receiving the first formal accounts of what had happened to their loved ones.

“They were brutal. They really were abusive – they humiliated us,” Ms. Spitzer said about the German and Bavarian officials.

Ankie Spitzer surveys the damage to her husband Andrei's room at the Munich Olympic compound in September, 1972.Handout

For half a century, the families campaigned for the governments to release the archives, take responsibility and pay compensation.

On Tuesday night, just days before the 50th anniversary of the attack and amid mounting pressure, the city, state and federal governments agreed to meet those demands.

Without the deal, Germany risked international embarrassment, with the families and Israeli government pledging to boycott the Sept. 5 commemorations.

Only days earlier, Ms. Spitzer told The Globe and Mail she was in disbelief: Five decades after her husband was killed, she was still fighting with German authorities.

Reaching an accord “would mean the world to me,” she said. “Because I would know that I cleaned the table, and I don’t pass the struggle on to my children and to the children of my children.”

An armoured car leaves a Munich military base on Sept. 6, 1972, after German authorities failed to free the hostages safely.EPU/AFP via Getty Images

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/ATDRGOLXZZDVXMLRE3PXDTPYNE.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/DEQSICH6OFB7VD3552SMULE3ZE.jpg)

All the families have accepted the deal, which their lawyers at Amsterdam-based Knoops’ Advocaten said was subject to a non-disclosure agreement at the request of German negotiators. Still, Reuters has reported that it includes €28-million ($36.6-million) in compensation, about five times what the government offered a few months ago.

Germany has also agreed to accept responsibility for its role, strike a commission of Israeli and German historians to study what happened and release archives, some of which were to remain classified until 2047, when, as Ms. Spitzer put it, she would be “long dead.”

In a joint statement, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and his Israeli counterpart, Isaac Herzog, said the agreement “recognizes the terrible suffering of the murdered and their relatives.”

Five decades ago, Ms. Spitzer was 26, her husband was 27 and their daughter was just two months old. The couple had met only a few years earlier in the Netherlands, where she grew up. He was visiting from Israel to improve his fencing skills.

Snapshots from their whirlwind romance show a beaming couple on their wedding day, the groom with bold glasses and even bolder sideburns, the bride in a wide-brimmed white hat and sunglasses. Fast forward a little more than a year and Mr. Spitzer is a dad smiling at a sleeping baby Anouk, whose shock of hair matches his.

“We were on top of our lives,” Ms. Spitzer said, remembering their young love and Mr. Spitzer’s excitement at going to the Olympics. The child of Holocaust survivors, he told his wife he believed the Games would be a place with no borders or enemies, where he could “reach out to everyone.”

Fencers salute Andrei and Ankie Spitzer at their wedding in 1971. Mr. Spitzer went to Munich as the coach of the Israeli fencing team.Handout

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/NYVVHM5NZBC2LCMVYRERBTNEMI.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/ESN5H6GKO5LJTCMMERMGWCW6RQ.jpg)

That perspective matched the ethos of the 1972 Olympics. Dubbed the “Happy Games,” Munich was where the world was supposed to see a new Germany. The entertainment, decorations and even the architecture were meant to be the antidote to the 1936 Olympics in Berlin and show the visiting athletes and TV audiences that Nazi Germany was dead and buried.

For more than a week, the Games lived up to that promise. But in the early hours of Sept. 5, eight members of Black September scaled a chain-link fence, triggering a cascade of events that would destroy families, leave a black mark on modern German history and further poison the relationship between Israelis and Palestinians.

The terrorists’ goal was twofold: Draw the world’s attention to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and use Israeli hostages to demand the release of more than 200 Palestinians imprisoned in Israel, said historian David Clay Large, the author of Munich 1972: Tragedy, Terror, and Triumph at the Olympic Games. Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir promptly refused the hostage takers’ demands for the precedent it would set. Their aim wasn’t bloodshed, but armed with Kalashnikov rifles and grenades they were prepared to kill for their cause, Prof. Large said. And when they did it was “brutal and cruel and unforgivable.”

Unwittingly helped over the Olympic Village fence by members of the Canadian team who thought the Palestinians were also athletes sneaking back into dorms, the terrorists broke into the Israeli quarters at 31 Connollystrasse.

In the initial struggle they killed wrestling coach Moshe Weinberg and weightlifter Yossef Romano and captured nine others, including Mr. Spitzer. Over the next 20 hours, negotiations stalled and two police rescue efforts failed. The first was called off when officials realized that what was supposed to be a covert ambush was being aired on live TV and watched by the terrorists.

The second went ahead despite the police being outnumbered and ill-prepared. The terrorists and hostages had been moved to an airfield in a ruse orchestrated by German police to ambush them again. In his book One Day in September, journalist Simon Reeve said the officers had neither the training nor the equipment to carry out the operation. “The action ended in disaster,” reads the blunt assessment on the Bavarian government’s website.

News of the massacre in The Globe and Mail's Sept. 6, 1972 edition. The death toll would later be revised to 11 hostages, five extremists and a German police officer.

It was made all the worse when the families and television audiences around the world were first told that the hostages had been saved, only to hear the crushing truth hours later.

Within a day, 11 coffins were loaded onto a plane for the trip home to Israel. And instead of the Munich Olympics being remembered as the debut of a new Germany, the tragedy reminded the world of the old Germany. In a city made notorious as the birthplace of Nazism, located just 30 minutes from Dachau – and just 27 years after the end of the Holocaust – Jewish people were again murdered in Germany for being Jewish.

The perpetrators weren’t German, but it was Germans who were left to deal with the massacre. “There is still a deep wound and even embarrassment on the German side,” said Michael Brenner, a professor of Jewish history at the University of Munich and American University in Washington.

Things went wrong from the start – and they continued to go wrong for 50 years, he said.

Just weeks after the attack, Germany rubbed salt in the wound when it released the remaining three terrorists in exchange for the passengers of a hijacked Lufthansa flight. The families’ lawyers, Alexander Knoops and Carry Knoops-Hamburger, said they uncovered evidence that the hijacking was initiated by West Germany to get rid of the terrorists, who then received a hero’s welcome in Libya. That allegation was also made in a 1999 Oscar-winning documentary, and the lawyers say the German government has never refuted the claim. The federal Interior Ministry declined to comment.

It’s an injustice that Ms. Spitzer said she can’t understand. How could her husband’s killer walk free while her daughter had to grow up without a father? “Why are these people not until the end of their lives in jail,” she asked.

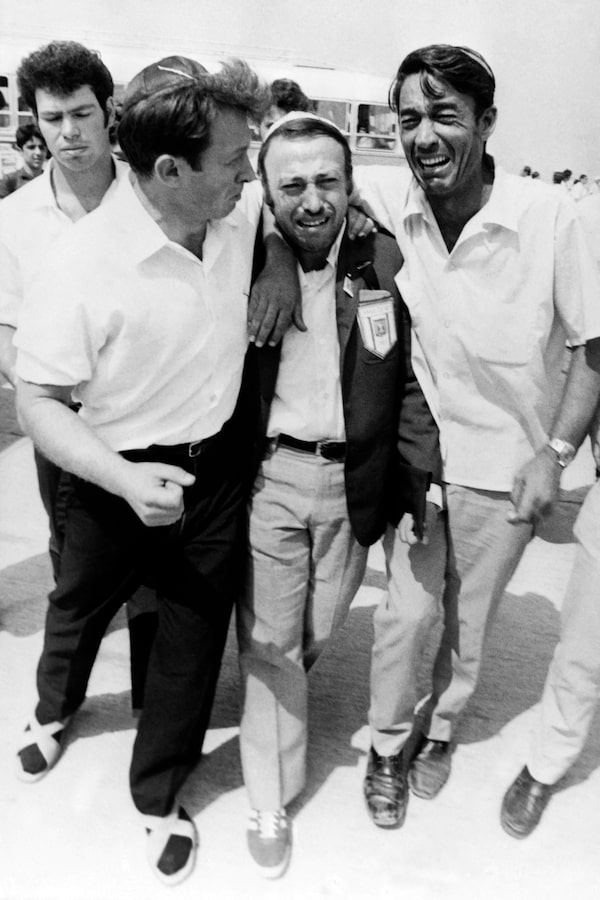

Relatives of Munich victims cry at a funeral in Tel Aviv in September, 1972.AFP via Getty Images

Some of those involved in the Munich massacre met a different fate. In retaliation, Israel launched “Operation Wrath of God,” in which agents tracked and killed people connected to the attack, but which also claimed the lives of innocent civilians. The response entrenched a pattern of reprisals and failed to improve Israel’s security, said Prof. Large, who is also a senior fellow at the Institute of European Studies at UC Berkeley.

To this day, Prof. Large said, Palestinians celebrate the Black September attack. Just weeks before the 50th anniversary, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz hosted Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas in Berlin. At a joint news conference, Mr. Abbas was asked if he would apologize for the massacre. He dismissed the question and accused Israel of committing “50 Holocausts” against Palestinians. The remarks drew widespread criticism, including of Mr. Scholz, who failed to immediately challenge the comments.

In a letter to Mr. Scholz last week, Bavaria’s Commissioner for Anti-Semitism, Ludwig Spaenle, urged him to reach a deal with the families. He described the response in 1972 as a “complete failure of the state” and said the German handling of the massacre in the subsequent decades “weighs just as heavily.”

It is “characterized by cover-up, concealment, suppression, even deception, lies and denial of responsibility,” he wrote to Mr. Scholz on Aug. 26. “It is an open wound in our country’s history.”

The first time Ms. Spitzer came face to face with that intransigence was a few months after Mr. Spitzer’s death, when she returned to Munich in search of the full story of her husband’s death. Over successive trips, the police and the coroner’s office insisted there was no information to share – a lie also maintained by officials in the state and federal governments.

Instead, they told her “dead is dead” and accused her and the Israeli athletes of bringing terrorism to German soil.

Ms. Spitzer holds the necklace, damaged by bullets, that her husband wore when he died.Maya Alleruzzo/The Associated Press

The wall of silence was finally broken in 1992 when a whistle-blower leaked 80 pages of documents to the families to prove the government had withheld information all along. Only then did the various levels of government acquiesce, and Ms. Spitzer finally learned how her husband died.

The revelations led the families to sue the German authorities for their mishandling of the terror attack. But by then the statute of limitations had passed. A subsequent out-of-court settlement largely went to legal fees, the families’ new lawyers said.

In the past decade, officials in Germany and the International Olympic Committee have tried to right some of the wrongs the families suffered. The final agreement with Germany follows the unveiling of a memorial to the victims five years ago and, last year, the first minute of silence in their honour at an Olympic opening ceremony.

All of it, though, comes painfully late. In 1972, the 11 Israeli victims left behind 34 parents, wives and children. Now there are just 23 left.

“I feel I’m also representing them,” Ms. Spitzer said, “because they don’t have a voice any more.”

With a report from Stephanie Chambers

Marieke Walsh

Marieke Walsh