Firefighters watch as they burn a fireline near the Bear Fire in Oroville, Calif., Sept. 10, 2020.Max Whittaker/The New York Times News Service

The alert buzzed on my phone at 7:49 the night of Aug. 23. The reservoir a short distance from my home was under a wildfire evacuation warning.

I have covered wildfires in California as a journalist for the past four years. But still I considered the danger to be confined mainly to the communities tucked into forests, mountains and canyons where I had witnessed so much destruction.

Wildfires were not supposed to be something that happened where I lived, in the suburban sprawl of strip malls, tract homes and freeways that make up much of Silicon Valley.

Thousands of homes threatened by wind-whipped wildfire in Northern California

My husband and I had been up to the reservoir, a popular gathering spot and drinking-water source, just days before. The sun had been shining and we had rolled our bikes down the tree-lined trail that runs from the reservoir to our home.

Then came what scientists have termed California’s “new normal” – the annual ritual of soaring temperatures, dry winds and wildfires that has made this state of 40 million people a bellwether for how modern society will cope with a changing climate.

A haze from wildfire smoke lingers over the gutted Medford Estates neighborhood in the aftermath of the Almeda fire in Medford, Oregon, U.S., September 10, 2020. Picture taken with a drone.ADREES LATIF/Reuters

As seemingly all of California started to burn, and fires spread through neighbouring Oregon and Washington – killing at least 25 so far – I began to appreciate just how much daily life here is defined by the constant threat of environmental disaster.

First, there was a heat wave that pushed temperatures into the 40s. Then came power outages as demand for air conditioning soared. Next was a phenomenon I had not heard of until I moved west: a “dry thunderstorm” that brought 14,000 lightning strikes, but little rain. Soon the skies were blanketed by smoke so thick it blocked out the blue rays of the sun, casting everything in an orange glow.

As the fires intensified, I began to think of what we might take if we had to evacuate. A neighbour shared a checklist: With two hours to prepare, we would have time to pack our most important belongings and heirlooms. With one hour, family photos would have to be sacrificed in favour of sleeping bags and clothing. The 15-minute checklist was short: eye glasses, prescription drugs and water. In reality, many of the evacuees I had met over the years had fled with little but the clothes on their backs.

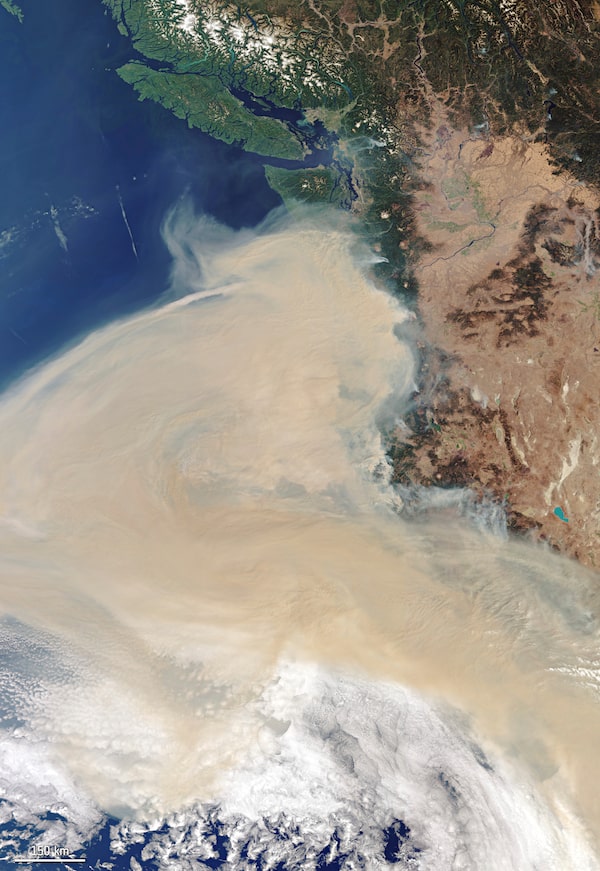

In this Thursday, Sept. 10, 2020 Copernicus Sentinel-3 image, provided by the European Space Agency, ESA, multiple fires can be seen hovering over the U.S. states of California, Washington and Oregon.The Associated Press

And where would we go in this region of six million people? Fires were burning to the west, threatening coastal communities of Santa Cruz and Big Sur. They were burning to the east in the mountains above San Jose. They were blazing to the south in places such as Carmel Valley, and to the north in Napa and Sonoma. Lake Tahoe seemed like a possibility. But the Sierra Nevada would, too, soon be ablaze.

I did a mental calculation of what it would take for the fires to reach our home. Flames would have to sweep down the Santa Cruz mountains, through the tony community of Los Gatos with its gated mansions in the foothills, jump an eight-lane highway, and torch the Netflix headquarters.

The chances seemed remote. But I had covered enough fires to know that they do not roll down hills and through streets like a wall of flame. They are wind-driven, often creating their own weather systems that can blow embers kilometres away, where they land in overgrown front yards and clogged eavestroughs.

No one, for instance, had thought the Tubbs Fire that tore through Santa Rosa in 2017 – killing 22 – would vault over a six-lane highway into the tidy subdivision of Coffey Park.

“These things don’t happen to us,” Coffey Park resident Jan Perry had told me as we toured what was once the kind of middle-class, 1980s-era neighbourhood that reminded me of the Toronto suburbs where I was raised. It was now a mess of blackened wood, melted aluminum and broken glass.

In this image taken with a slow shutter speed, embers light up a hillside behind the Bidwell Bar Bridge as the Bear Fire burns in Oroville, Calif., on Wednesday, Sept. 9, 2020.Noah Berger/The Associated Press

She handed me a charred scrap from a Bible that had landed in her front yard. It read: “Thou shalt be visited by the Lord of hosts with thunder, and with earthquake, and with great noise, with storm, and tempest and the flame of devouring fire.”

To Ms. Perry, and others I met that year, the 2017 fire season had served as a prophecy, a warning that worse was to come.

“Over a decade there will be more fire, more destructive fire, more billions that will have to be spent on it, more adaptation and more prevention,” then-governor Jerry Brown, a Jesuit scholar, had said at the time.

My first year covering California’s wildfires, I had wanted to stay as close to the action as possible. I had driven until I spotted the red glow of a blazing hillside and checked into a hotel across the street, spending a sleepless night marvelling at the strange beauty of the flames.

A Coulson 737 firefighting tanker jet drops fire retardant to slow Bobcat Fire at the top of a major run up a mountainside in the Angeles National Forest on September 10, 2020 north of Monrovia, California.David McNew/Getty Images

Four years later, I have grown tired of the unrelenting stress of life with wildfires. Helicopters whirl constantly overhead. Everything is coated in a fine layer of ash. Each new day brings another air-quality alert that explains my stuffed nose and headaches.

In the end, we opted not to evacuate and the next morning I ventured into the smoke-filled streets to pay some bills at the bank. This, we have been told, is evidence of the resilience of Californians, for whom life goes on in spite of environmental catastrophe. But it is starting to seem less like resiliency and more like a form of post-traumatic stress.

“Fire comes because the earth needs it. We understand that it’s part of nature,” Maria Calderon, an artist, had told me in 2017 as she wept over the loss of her home in picturesque Ojai Valley. “But people are not programmed to regenerate the same way that nature does.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.