San Diego firefighters help Humberto Maciel rescue his dog from his flooded home in Merced, Calif., on Jan. 10.JOSH EDELSON/AFP/Getty Images

More than a dozen people are dead in California after pounding rain laced with hail descended on parts of the state, felling trees, inundating roads, flooding homes, severing power lines and swallowing at least one car into a sink hole. Thousands were evacuated from areas prone to mudslides and flood-watch warnings covered the homes of 90 per cent of Californians.

But the weather emergency has also brought some hope to a state where water shortages have grown increasingly dire, after a 2022 that was globally the fifth-hottest on record. The wickedly wet weather has delivered a bounty of snow to the Sierra Nevadas, the mountain range whose meltwaters flow through taps used by 23 million people in California. Monitoring by the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows snow quantities throughout the Sierra Nevadas are now more than double typical amounts; some basins have seen quadruple the median levels of winter precipitation, which is measured as “snow water equivalent.”

For those worried about drought, “no one in their right mind would complain about what’s going on, my heavens,” said Jack Schmidt, a watershed scientist at Utah State University.

After nearly a quarter-century of drought across the U.S. southwest, mountainous regions in Utah, too, have seen nearly twice the normal snowfall. In the upper basin of the Colorado River, the vital waterway whose declining flows have struck deep alarm across the southwestern U.S., snowpack levels stand 42 per cent above the median for this time of year. Even in Arizona, the mountains north of Phoenix have seen 50-per-cent more precipitation than normal.

None of it is enough to dispel the deep foreboding that decades of drought have brought to the region. Even a record-setting year would deliver only modest new volumes to parched Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the Colorado River reservoirs whose dried-out shores have become symbols of a water emergency that threatens tens of millions of Americans, and the far greater number of people who rely on the fruits, vegetables and nuts grown on irrigated land in Arizona, California and New Mexico.

This winter is far from over. A dry February could arrive. A warm March could sublimate large quantities of snow, sucking moisture into the atmosphere instead of releasing it as snowmelt runoff.

But for now, the precipitation has brought a glimmer of optimism, Prof. Schmidt said. “Does this prevent us from going over the cliff? Yes – if everything works out.”

The atmospheric rivers slamming into California brought havoc on the coast and at higher elevations. In Los Angeles, water coursed through a pedestrian tunnel in Union Station, the city’s main rail and subway nexus, while five-metre-high waves slammed into beaches north of the city. Some schools moved to online learning as landslides and over-flooding closed roads.

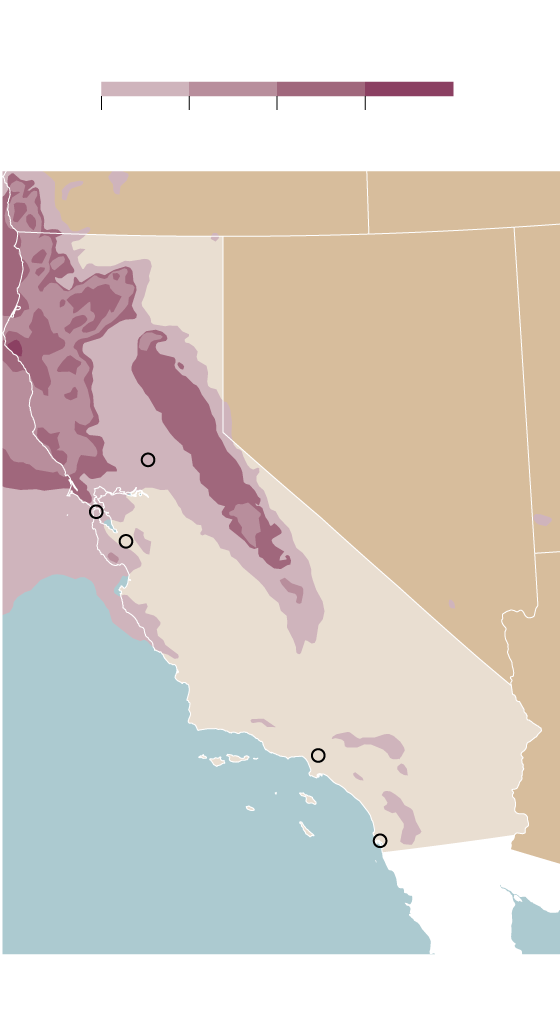

Five-day precipitation forecast

In centimetres, as of Jan. 10

5

10

15

25

OREGON

NEVADA

Sacramento

San Francisco

San Jose

CALIFORNIA

Los Angeles

San Diego

Pacific Ocean

MEXICO

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NATIONAL OCEANIC

AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION

Five-day precipitation forecast

In centimetres, as of Jan. 10

5

10

15

25

OREGON

NEVADA

Sacramento

San Francisco

San Jose

CALIFORNIA

Los Angeles

Pacific Ocean

San Diego

MEXICO

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NATIONAL OCEANIC

AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION

Five-day precipitation forecast

In centimetres, as of Jan. 10

OREGON

5

10

15

25

NEVADA

UTAH

Sacramento

San Francisco

San Jose

CALIFORNIA

ARIZONA

Los Angeles

San Diego

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NATIONAL OCEANIC

AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION

MEXICO

In San Francisco, authorities issued a flash-flood warning for the entirety of downtown. Video from the city posted to social media showed a lashing of rain and hail so intense it resembled a blizzard. Dozens of lightning strikes fell upon the area and several tornado warnings were issued.

One was two kilometres from where Ryan Hollister lives in northern San Joaquin Valley. The temperature dropped suddenly, and the area was “pummelled with very intense rainfall rates and gusty wind,” said Mr. Hollister, who teaches earth science at California State University, Stanislaus and Modesto Junior College.

San Francisco has recorded more than 31 centimetres of rainfall since Boxing Day, a half-year’s worth of precipitation in two weeks and the city’s soggiest 15 days on record since 1866. Across the state, nearly 200,000 people have lost electricity.

Some of the blow was softened by local reservoirs that “have a large amount of flood-absorbing capacity due to the multiyear drought,” Mr. Hollister said. That kept some rivers from flooding.

In the mountains, meanwhile, great mounds of snow accumulated. On Tuesday morning, Mammoth Mountain, the ski resort 400 kilometres east of San Francisco, reported 150 centimetres of snowfall from the storm system with another 60 or more expected. January has barely begun, and the resort has already surpassed last year’s total snowfall.

In Mammoth Lakes, Calif., the pile of snow cleared from John Wentworth’s driveway now stands more than six metres high. “It’s an extremely significant event. And we’re very grateful for it,” said Mr. Wentworth, the mayor of Mammoth Lakes who has also served on a climate adaptation and resiliency advisory body to California Governor Gavin Newsom.

But while the current storms may bring needed water, he said, “there’s the nagging anxiety about what the trends are telling us – and the trends are a little bit of a buzzkill.”

Globally, the last eight years have been the hottest on record, the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service reported Tuesday. Last week, new research found that without major intervention, Utah’s Great Salt Lake will go dry in five years.

In the Colorado Basin, the regional drought is so severe that it would take six banner years to reverse accumulated water losses.

“One good winter is going to be a start,” said Steven Fassnacht, a snow hydrologist at Colorado State University, but its impact will be modest at best.

“It’s not like one good year, everyone has lots of water and we’re all good.”

Not only is it too early to measure exactly what bounty of precipitation this winter has brought – in the upper reaches of the Colorado, March and April tend to be most important for snow accumulation – but the current deluge brings its own kind of risk.

In the dry times, fear of the deepening water crisis has motivated efforts to address a drought that has now lasted decades.

This year, temptation will mount “to say, ‘Oh it’s a wet year, we have no problem,’” said Prof. Schmidt.

What’s needed instead, he said is a relentless effort to reduce consumption in a river system that is delivering a quarter less water than cities and farmers expect to use.

For California, meanwhile, the deluge has underscored a changing water reality that Governor Newsom described last summer when he announced a drought response plan for the state. California, he said at the time, continues to receive sufficient precipitation for its needs – but as the climate changes, it often arrives with such intensity that it washes away rather than being saved for later use.

For California to see water flowing out to sea, “that looks like money going down the drain,” said Charles Hillyer, an irrigation specialist who heads the California Water Institute at California State University, Fresno.

Much of the state’s drought response plan involves finding new ways to bank those resources.

One idea involves using existing irrigation canals to deliver flood waters to agricultural fields, where they can be injected below ground to recharge aquifers. The concept has yet to be tested and proven but suggests a way forward for California.

“The climate has changed, it’s going to continue to change, and we need to change in response to it,” Prof. Hillyer said.