Imagine an electric-powered elevator that carries humans and cargo up a freestanding, inflatable structure 20 kilometres above the Earth's surface – to a platform used to launch space missions.

Pembroke, Ont.-based Thoth Technology Inc. was granted U.S. patent for its space elevator idea last month – just the latest in a concept that has captivated developers and science-fiction aficionados for decades.

The idea seems far-fetched – but so do other far-out ideas. Such projects face huge obstacles, such as finding a wealthy patron, developing and scaling up technology and making the project work as a business model.

We spoke to engineering and space experts about several ambitious projects – including the space-elevator project – at different stages of development.

SPACE ELEVATOR

An artist’s rendering shows the final part of the 20-kilometre-tall space elevator platform recently patented by Thoth Technology of Pembroke, Ont.

HANDOUT/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Professor Arun Misra, director of the Space Flight Dynamics Lab at McGill University, knows space elevators. The researcher is part of the International Academy of Astronautics working group on space elevators that studies theoretical concepts that could travel 10,000 to 100,000 kilometres above the Earth.

Asked about the relatively modest 20-kilometre space-elevator idea, he responded, "One has to start somewhere." While much of the technology is within reach, the cost of the project would be significant, he added.

Dr. Misra sees increasing space travel, including space tourism, as inevitable. It costs anywhere between $25,000 and $50,000 to deliver a kilogram of cargo to space – depending on the altitude, he explained.

"At this cost, obviously there cannot be that much space travel. So the cost has to come down. People are working on various concepts on how to reduce costs," he said.

The Canadian elevator design could achieve that. Blasting off from Earth's stratosphere would be 30 per cent cheaper than conventional rockets currently used to propel astronauts and supplies to space from the planet's surface, according to Thoth.

It all sounds a bit Arthur C. Clarke. The science-fiction writer popularized the idea in his 1979 novel The Fountains of Paradise, in which engineers build a space elevator on a mountain peak on the mythical island of Taprobane.

"We often talk about science fiction coming true in the form of science, but really it's engineering that makes science fiction become science. So a story such as this speaks more to the power of imagination and it speaks to possibilities," said Dr. Ishwar Puri, dean of engineering at McMaster University in Hamilton.

The boldness and imagination of the project has to be tempered by reality – how to maintain the structural integrity of such a tall tower, and to withstand the potentially hostile environment of strong winds and storms, he added.

VIRGIN GALACTIC

The Virgin Galactic project, the brainchild of British billionaire Sir Richard Branson, is very much about commercializing space travel. It is developing a spacecraft to carry paid passengers to space and back – and so far it has been a bumpy ride.

A spacecraft test flight last year crashed and killed one of its two pilots. The project has faced several other technical challenges – what kind of fuel to use and how to break the 70,000-feet height level, far short of the 350,000 feet the spacecraft aims to reach in order to give passengers the floating-in-space experience.

Dr. Misra of McGill University sees the Virgin Galactic project and the space-elevator idea as two extremes on a technological spectrum.

"Virgin Galactic [spacecraft] can be developed soon, and in the next five years if they have space tourists, it will not be surprising. But if, before 2050, somebody comes up with how to produce carbon nanotubes in large scale in the next 20 years, I will be surprised," he said.

Carbon nanotubes are the building blocks of possible space elevators, and their molecular structure makes them stronger than steel, he explained.

Dr. Puri of McMaster University warns against focusing only on Virgin Galactic's technical challenges and ignoring the social implications of space travel. "Once ordinary people have the possibility to go to space, you never know what the possibilities are," he said, pointing to the discussion around space colonies.

STRATOLAUNCH

The Stratolaunch has a wingspan of 385 feet – longer than a football field – and is fitted with six Boeing 747 engines. It needs 12,000 feet of runway to take off, 4,000 feet longer than the runway needed for large, wide-body passenger aircraft.

Like the Virgin Galactic, it aims to launch a spacecraft from midair. It, too, has a wealthy patron.

Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen has pumped more than $200-million of his own money into the project.

Innovation comes in different ways – either though engineering advances or packaging current technologies, according to Dr. Puri.

The Stratolaunch, for which flight testing might be possible in 2016, uses "technologies that we have off the shelf, putting them together in different ways and making things possible that monopolies or government entities weren't able to do for a long time," he said.

But the project faces business challenges. Companies like SpaceX and Orbital ATK are leading the way and have NASA contracts to deliver cargo to the International Space Station and to carry out manned missions to space, Dr. Misra explained. He draws a parallel with competition in the smartphone market.

"It's not that BlackBerry can't build good handsets, but they are having difficulty competing with Apple, for example," he said.

HYPERLOOP

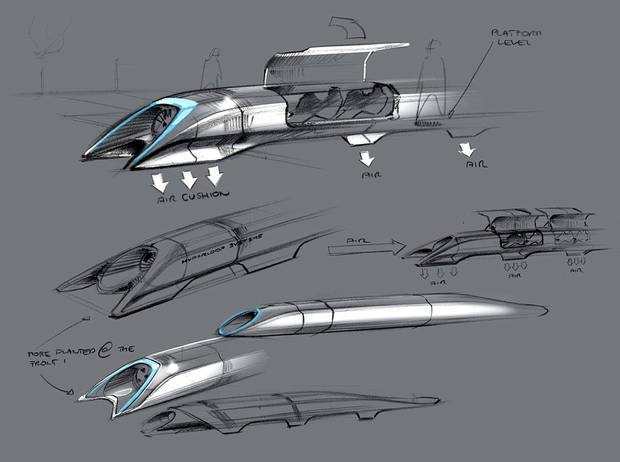

A design sketch released by Tesla Motors shows the Hyperloop passenger transport capsule.

TESLA MOTORS/ASSOCIATED PRESS

San Francisco to Los Angeles in 30 minutes – the tantalizing promise of super high-speed travel that would cover the 645 km between the two cities at a speed of more than 1,200 km/h.

Entrepreneur Elon Musk's idea of supersonic travel got a boost with news this year that construction on an 8-km test track would get under way in California next year. Hyperloop uses a system of depressurized tubes and magnets to propel travellers in a pod at high speeds.

Mr. Musk, who is also behind the Tesla electric-car line and space-travel enterprise SpaceX, has described the high-speed travel idea as a "cross between a Concorde and railgun and an air hockey table."

The project would require advanced manufacturing and test the limits of design and use of materials, explained Dr. Puri of McMaster. But the underlying challenge is bringing the cost down.

"A hyperloop mechanism that connected Hamilton to Toronto would be greater than the $20 round-trip," he said. "How possible will it be for people like you and me to afford it?"

Dr. Misra wonders whether the Hyperloop project fills an actual need. Mr. Musk's other big idea – SpaceX – filled the gap after NASA wound down its space-shuttle program, he said. But in Europe, China and Japan, high-speed train technology is already being used to move travellers efficiently, he said.

PROJECT LOON

Google X, the research arm of the tech giant, is behind an innovative attempt to expand Internet access to two-thirds of the world's population by using floating balloons.

Imagine choreographing thousands of balloons in the Earth's stratosphere – or about 20 km above the surface – and using software algorithms to position the balloons to achieve uninterrupted Internet service.

The company is partnering with cellphone providers such as Vodafone in New Zealand. The goal: 100-per-cent geographic coverage.

Dr. Puri sees this kind of project as a solution for remote areas and parts of the world affected by natural disasters, and where Internet links can be disrupted easily.

Dr. Misra said the project is technologically possible and has Google's resources and dollars to succeed. There is the question of whether balloons can be positioned correctly as they move through the stratosphere without losing Internet connection on the ground. But Dr. Misra does not see that as a problem.

"GPS – they're a bunch of satellites which provide you with GPS signals. They're all moving, all the time. This sort of technological problem has already been solved," he said.