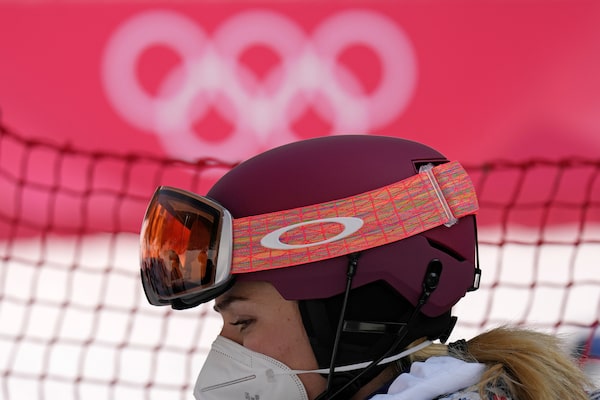

Skier Mikaela Shiffrin of Team USA sits by the side of the course after the women's slalom at the Beijing Olympics on Feb. 9.Robert F. Bukaty/The Associated Press

More below • How does Olympic alpine skiing work? A visual guide

As an athlete, you can have a good Olympics, a bad Olympics or whatever sort of Olympics American downhill racer Mikaela Shiffrin is having. If agony is one polar end of sports, Shiffrin is starting to push its limits into something worse.

A skier who almost always completes her courses, Shiffrin couldn’t manage that in her first appearance in the giant slalom on Monday.

“I’m not going to cry about this, because that’s just wasting energy,” she said.

On Wednesday, it happened again, this time in slalom, and almost identically. A few turns through the course and then out.

After her mistake, Shiffrin floated over to one side of the run and dropped to the ground. She sat hunched in the snow, arms cradling her knees, head down. A member of Team USA eventually came out to sit down next to her and console her. It took several more colleagues to coax her down off the mountain. While she sat there, other racers continued their work.

A teammate consoles Shiffrin.Robert F. Bukaty/The Associated Press

Shiffrin was there for more than 20 minutes. I don’t care how thermal your suit is. That’s a long time to sit in the snow.

Her eventual interview with NBC, the network that has spent the past four years pumping Shiffrin’s tires to the point of bursting, was a portrait of misery.

Clearly crying under her mask, unable to string whole sentences together, Shiffrin tried explaining what had happened. Asked if she “second-guessed” herself – the sort of bad question that sometimes elicits good answers – Shiffrin shrugged inconsolably.

“Pretty much everything makes me second-guess, like, the last 15 years, everything I thought I knew about my own skiing and slalom and racing mentality.”

Oh.

Shiffrin in action at the slalom event. 'I’m not going to cry about this, because that’s just wasting energy,' she said of her performance.Robert F. Bukaty/The Associated Press

How did someone who’s won two Olympic golds (2014 and 2018) and more World Cup slalom races (47) than most people have seen on TV end up here?

Shiffrin is the human fulcrum where great talent meets huge expectation.

As the weight of the latter increases, it gets progressively more difficult to maintain contact with the former.

Some athletes have the advantage of competing in automatic sports, ones that involve muscle memory and very little need of volitional thought. Michael Phelps (to whom Shiffrin has often, and wrongly, been compared) jumps in the pool and goes.

The pool never changes. Same distance and just as wet every time.

Every downhill ski course is different. It forces you to think. Once you add the Olympics into your mental process, forget about it. Seriously. Just try forgetting about it. It’s hard.

Shiffrin skis to the finish line.Denis Balibouse/Reuters

For an athlete of Shiffrin’s stature, there is another level of pressure. People need something to talk about. If you win, you’re it. If you don’t win, more’s the better.

NBC hired Shiffrin’s professional frenemy, Lindsey Vonn, to do commentary here.

Ahead of her run on Wednesday, Vonn said, “This is a must-medal situation for Mikaela. The stakes could not be higher.” And here’s Vonn afterward (on Twitter): “Gutted for [Shiffrin] but this doesn’t not take away from her storied career and what she can and will accomplish going forward.”

So which is it? Must-medal or shrug it off?

In sports TV Land, it’s both. They pile a bunch of crap on you, enough to crush any normal person. When you fold up under the pressure they created, they give you a pass. Some creative contrarian with access to a keyboard says that, actually, you are a loser (despite all those other wins). That allows the TV people – again, the ones who created a lot of this mess – to come rushing in with their dukes up ready to fight anybody who isn’t Team Shiffrin all the way.

If that push-pull gets too boring, or if you’re mean in an interview after having your spirit yanked out of your body, your TV friends will switch to Team Anyone But Shiffrin (ask Ryan Lochte). Twenty years later, they’ll do a 30 for 30 about how abominably you were treated by the media.

Shiffrin leaves the finish area.Luca Bruno/The Associated Press

How do you disassemble this carousel of unfairness?

Are you kidding me? You don’t. Few things in the media business work so well to the mutual benefit of all involved.

Remember the last time you watched a World Cup slalom race? I’m just kidding. You’ve never watched one.

You don’t watch those races, but you may watch the one in Beijing for the same reason that a once-in-a-generation athlete like Shiffrin is so gutted after overshooting a single gate in a career littered with thousands of them. Because this one matters more.

Shiffrin’s job isn’t skiing. It’s skiing so well that people want to watch her do it. That desire is rendered monetary through the steady application of media hype.

This is what is missing from the new discussion about athletes and pressure.

If there is no pressure, there may be fewer unhappy elite athletes. But there may be fewer elite athletes period, because people have stopped caring. Without risk, there are only limited rewards.

It’s possible you still don’t know much about Mikaela Shiffrin or skiing. But if you’ve seen Wednesday’s clip, you’re invested now. You probably want this remarkably successful, super wealthy, impossibly privileged rock star to make it all right with a win.

You may want that so much that you make a space in your day to watch it. A small percentage of those people may end up being so captivated that they end up following the pro ski circuit after the Olympics ends.

That’s how this sports racket works. Sure, it’s powered by triumph. But it runs just as smoothly, maybe better, on tears.

How does Olympic alpine skiing work? A visual guide

BEIJING 2022

SCHEDULE

Qualification

Medal

FEBRUARY

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Alpine skiing is one of the signature events at the Winter Olympics, with athletes flying down the mountain at breathtaking speeds. Olympic skiers can reach speeds of 128 to 150 kph as the crouching position allows racers to minimise air resistance.

Men’s and women’s Alpine skiing debuted at Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1936 with the Alpine Combined event comprising of a downhill and a slalom run

All competitors must wear a crash helmet for the race

Racing suit

Goggles

Gloves

Gate

Shin guards

Skis with

ski brakes

Ski poles to guide turns, help skier maintain balance

COMPETITION FORMAT

Against-the-clock format, competitors attempt to cross the finish line in the fastest time

TECHNICAL EVENTS

Each skier completes two courses – not revealed until raceday – with no practice runs. The winner is the skier with the quickest combined times.

Slalom

Giant Slalom

Gate width

4m-6m

Gates

45-75

Gate width

4m-8m

Gates

28-68

Elevation/

vertical

drop

Gate

distance

0.75m-13m

Gate

distance

Min. 10m

Men

180-220

Men

300-450

Women

140-200

Women

300-400

ELEVATION DROP — IN METRES

SPEED EVENTS

Skiers make a single run, with the quickest time taking gold. Speeds reach 130-160 kph. Downhill practice runs are not only allowed but required

Super-G

Downhill

Gates delineate racing line

Gate width

6m-12m

Gates

28-45

Open gate

Closed

gate

Gate

distance

Min. 25m

Gate

width

Min. 8m

Men

400-650

Men

800-1,100

Women

400-600

Women

450-800

ELEVATION DROP — IN METRES

OTHER EVENTS

Alpine Combined

Consists of a Downhill run followed by Slalom

Competitors must complete a successful downhill run to advance to the Slalom run

Mixed Team Parallel

Teams comprise two men and two women

Two teams compete simultaneously against each other in a parallel slalom race

SOURCE: REUTERS

BEIJING 2022

SCHEDULE

Qualification

Medal

FEBRUARY

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Alpine skiing is one of the signature events at the Winter Olympics, with athletes flying down the mountain at breathtaking speeds. Olympic skiers can reach speeds of 128 to 150 kph as the crouching position allows racers to minimise air resistance.

Men’s and women’s Alpine skiing debuted at Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1936 with the Alpine Combined event comprising of a downhill and a slalom run

All competitors must wear a crash helmet for the race

Racing suit

Goggles

Gloves

Gate

Shin guards

Skis with

ski brakes

Ski poles to guide turns, help skier maintain balance

COMPETITION FORMAT

Against-the-clock format, competitors attempt to cross the finish line in the fastest time

TECHNICAL EVENTS

Each skier completes two courses – not revealed until raceday – with no practice runs. The winner is the skier with the quickest combined times.

Slalom

Giant Slalom

Gate width

4m-6m

Gates

45-75

Gate width

4m-8m

Gates

28-68

Elevation/

vertical

drop

Gate

distance

0.75m-13m

Gate

distance

Min. 10m

Men

180-220

Women

140-200

Men

300-450

Women

300-400

ELEVATION DROP — IN METRES

SPEED EVENTS

Skiers make a single run, with the quickest time taking gold. Speeds reach 130-160 kph. Downhill practice runs are not only allowed but required

Super-G

Downhill

Gate width

6m-12m

Gates

28-45

Gates delineate racing line

Open gate

Closed

gate

Gate

distance

Min. 25m

Gate

width

Min. 8m

Men

400-650

Men

800-1,100

Women

400-600

Women

450-800

ELEVATION DROP — IN METRES

OTHER EVENTS

Alpine Combined

Consists of a Downhill run followed by Slalom

Competitors must complete a successful downhill run to advance to the Slalom run

Mixed Team Parallel

Teams comprise two men and two women

Two teams compete simultaneously against each other in a parallel slalom race

SOURCE: REUTERS

BEIJING 2022

FEBRUARY

SCHEDULE

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Qualification

Medal

Alpine skiing is one of the signature events at the Winter Olympics, with athletes flying down the mountain at breathtaking speeds. Olympic skiers can reach speeds of 128 to 150 kph as the crouching position allows racers to minimise air resistance.

Men’s and women’s Alpine skiing debuted at Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1936 with the Alpine Combined event comprising of a downhill and a slalom run

Ski poles to guide turns,

help skier maintain

balance

All competitors must

wear a crash helmet

for the race

Racing

suit

Goggles

Gate

Gloves

Shin guards

Skis with ski brakes

COMPETITION FORMAT

Against-the-clock format, competitors attempt to cross the finish line in the fastest time

TECHNICAL EVENTS

Each skier completes two courses – not revealed until raceday – with no practice runs. The winner is the skier with the quickest combined times.

SPEED EVENTS

Skiers make a single run, with the quickest time taking gold. Speeds reach 130-160 kph. Downhill practice runs are not only allowed but required

Super-G

Downhill

Slalom

Giant Slalom

Gate width

6m-12m

Gates

28-45

Gate width

4m-6m

Gates

45-75

Gate width

4m-8m

Gates

28-68

Gates delineate racing line

Open gate

Elevation/

vertical

drop

Closed

gate

Gate

distance

Min. 25m

Gate

width

Min. 8m

Gate

distance

0.75m-13m

Gate

distance

Min. 10m

Men

400-650

Men

800-1,100

Women

400-600

Women

450-800

Men

180-220

Women

140-200

Men

300-450

Women

300-400

ELEVATION DROP — IN METRES

ELEVATION DROP — IN METRES

OTHER EVENTS

Alpine Combined

Mixed Team Parallel

Consists of a Downhill run followed by Slalom

Competitors must complete a successful downhill run to advance to the Slalom run

Teams comprise two men and two women

Two teams compete simultaneously against each other in a parallel slalom race

SOURCE: REUTERS

Beijing 2022: More from The Globe and Mail

Ice dancing in depth

What kinds of technical skill and artistry go into a winning ice-dance performance? Globe and Mail videographer Timothy Moore spoke to Canadian skaters Piper Gilles and Paul Poirier and one of their coaches to find out. Subscribe for more episodes.

More from Cathal Kelly

That’s it, that’s all, the Peng Shuai saga is over. Right?

Eileen Gu is golden in first Beijing Olympic event – and right on cue

Complaining at the Olympics? That’s nothing new. What’s changed is our perspective

Our Olympic team has a daily newsletter that lands in your inbox every morning during the Games. Sign up today to join us in keeping up with medals, events and other news.

Cathal Kelly

Cathal Kelly