Graham Dickinson stands on a precipice near the peak of Tianmen Mountain in remote, central China.

With an hour before sunset on Jan. 25, light winds and a temperature hovering around 5C create reasonable working conditions for Dickinson, a BASE jumper and wingsuit pilot who jumps off cliffs and out of planes for a living.

Dickinson, just a week removed from his 29th birthday, is a couple hundred metres above the ground. He's surrounded by a chain of mountains that thrust skyward from the jungle below. The Canadian daredevil is in the final moments before taking flight in his latest thrill-seeking endeavour.

He knows the area well and has always meticulously planned his jumps: Measured altitude and slope with a laser rangefinder, pored over topography data, and often studied video.

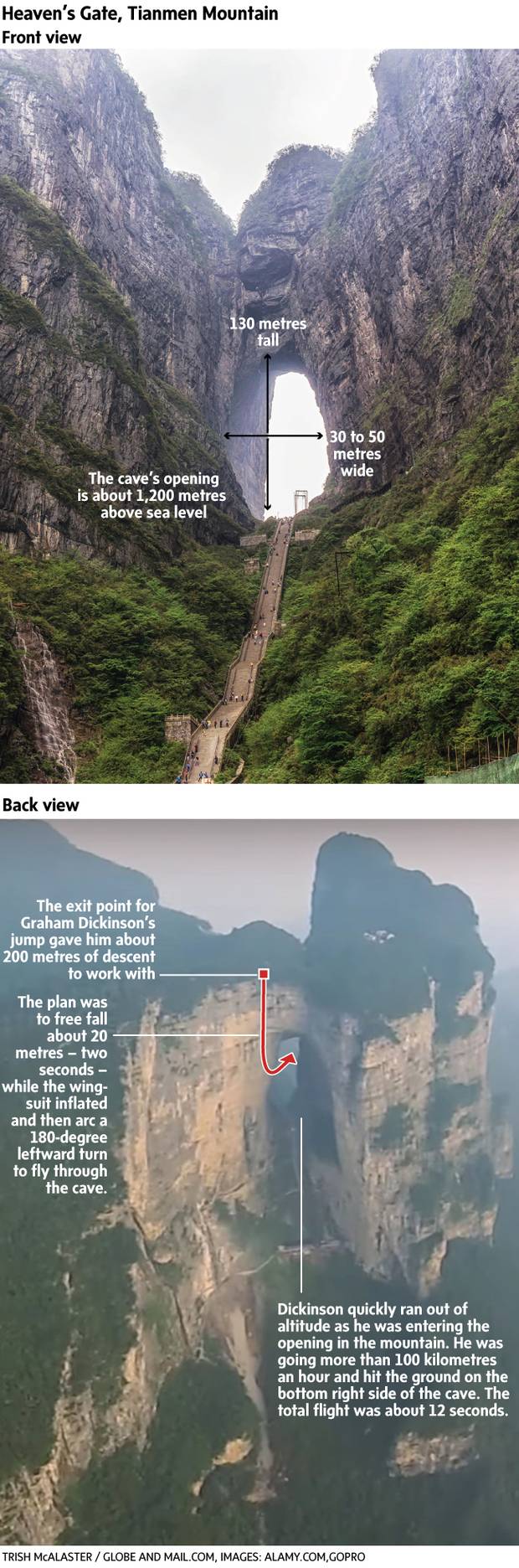

Today, Dickinson is ready to conquer a flythrough of Heaven's Gate, the opening in the rock face, roughly the size of a football field, that goes clear through the mountain on which he's standing.

He will jump from the cliff and attempt to manoeuvre a 180-degree turn in order to fly back through the celestial archway. Tourists visit it in droves in the summer to pray for a healthy life. In the winter, it's quiet – and solitude suits him when he jumps.

Other BASE jumpers would call this attempt particularly risky. Even among the most daring in this extreme sport, Dickinson is known for his willingness to plunge headlong into danger.

Clad in his wingsuit, which hangs on his body like a sleeping bag, Dickinson is poised to fly.

Everything he thought about

BASE jumping, a sport in which jumpers leap from bridges, antennas, structures, and earth, was popularized by Carl Boenish. In 1978 the American was among the first to jump off El Capitan, a rock formation in California's Yosemite National Park.

Functioning wingsuits were introduced in the mid-1990s by French skydiver Patrick de Gayardon, moving the sport away from parachuting and toward something that resembles actual flying.

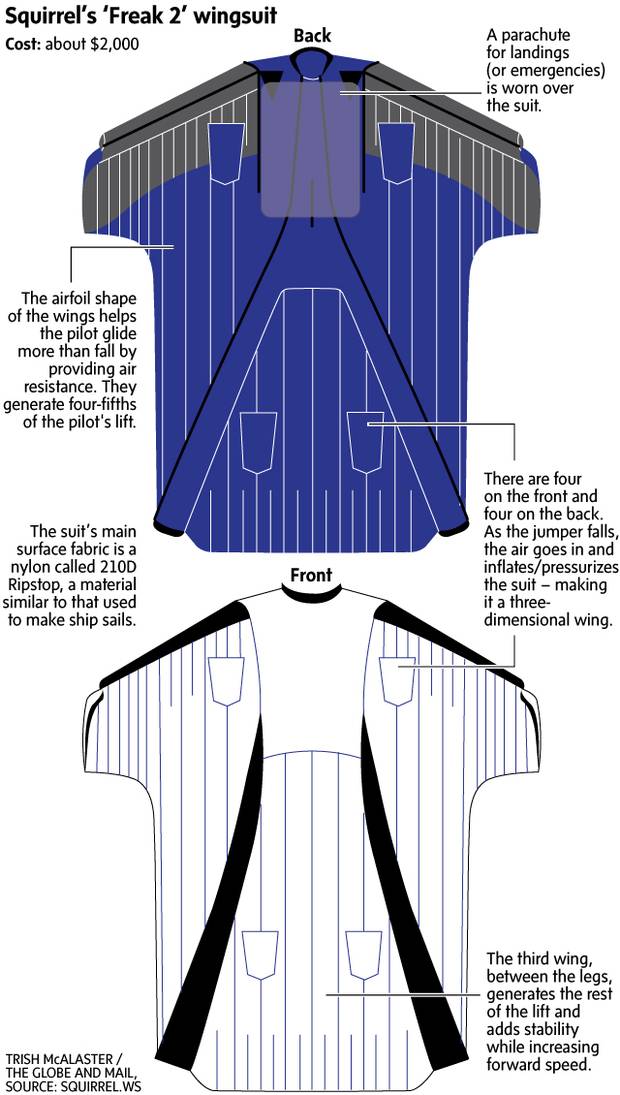

A modern wingsuit, when fully inflated, makes the wearer look like a flying squirrel. Strong nylon fabric connects the inside of each arm with the body, creating two wings. A third wing between the legs completes the squirrel image.

As air rushes through the inlets the suit inflates and the three wings become rigid. There are no controls. Movements of the body steer the flight. For each metre of vertical descent, a pilot can cover three horizontal metres, flying at a downward angle and hurtling as fast as 200 kilometres an hour. Toward the end of a flight, the pilot pulls the chute. The suit Dickinson wears at Tianmen Mountain is called the Freak 2, known for its agility, one of 11 models manufactured by Squirrel, a company that specializes in wingsuits and BASE jumping equipment.

There are likely fewer than one thousand active participants worldwide who BASE jump with a wingsuit, though its popularity has grown since the early 2000s.

Tech and social-media companies such as Facebook, GoPro and YouTube have expanded the sport's reach, pushing the intense visuals of wingsuit flying to wider audiences online, where Dickinson's profile grew. His videos, shot on a headcam and by fellow pilots, give viewers a jaw-dropping perspective of humans in flight.

When he was a kid growing up in the Toronto suburbs, his most extreme sports were gymnastics, dirt biking and snowboarding.

As a 16-year-old, Dickinson watched with envy as his older brother Evan started skydiving, but his parents wouldn't allow Graham to try it for himself. Instead, he obsessively watched videos online and began jumping from planes as soon he turned 18.

By the time he was 23, he made his first BASE jump.

It was the spring of 2011, in the middle of the night. He and Evan scaled a fence, climbed a 150-metre antenna and jumped. Dickinson was scared, but after his first go, he was hooked.

"It literally consumed my life and became everything I thought about," Graham would say about the life-changing experience.

The greatest feeling

Knowing the dangers of BASE jumping and wingsuit flying, why do people do it? Studies show risk-takers rank high on the scale of sensation seekers – not unlike drug users. The same brain chemical, dopamine, is at play, but it's more than reckless abandon.

"Obviously, nobody should be doing it at all. You're jumping off a cliff in a straitjacket that inflates. It's a pretty ridiculous thing to do. But for anybody who hasn't done it, they don't know why," Evan said. "Until you do it, you don't know why you would want to. It's the greatest feeling I have ever experienced."

Having two sons with a large appetite for risk and thrill-seeking was not easy on their parents, Pat and Norm. But Graham always tried to reassure them.

"Mom, Dad, this is my life," the free spirit who lived simply and with few possessions told them. "This is what I want."

After an illegal BASE jump in 2014 from a gondola in Whistler, police sought to charge Dickinson for damage to the unit. But before they could, he'd left Canada for Dubai. He worked there as a wingsuit coach at a skydiving operation. For a while, he had slept at the airport and later camped in the desert near work. He was fired from the job after an illegal BASE jump from a Dubai tower.

Doubling down on his dedication, from late 2014 through 2015, he spent about 2,000 hours – the equivalent of an office-bound work year – to explore and fly in the mountains northeast of Dubai, often with then-girlfriend Kristen Johnson.

Dickinson flew from more than a hundred never-jumped-before cliffs. He began to perfect proximity flying, the act of gliding just metres above the ground, the kind of terrain flying that produced the most intense rush and the most incredible visual footage.

During this period of his adventures, he was flying miles from any towns, and if something went wrong, Johnson said, "it probably meant dying out there."

They talked about risk and mortality. "He wasn't afraid of death," she said.

In the summer of 2015, they headed to Europe. There Dickinson met and impressed Jeb Corliss, a BASE and wingsuit legend. Corliss was the only pilot to successfully complete a flythrough of Heaven's Gate, when he jumped from a helicopter in 2011.

It was around this time that Dickinson pulled off his biggest and most daring jump caught on camera. Filmed by close friend and wingsuit pilot Dario Zanon, the 70-second video, shot at the mountain Le Brévent in France, has been viewed more than 10 million times online. Before he jumps, Dickinson shouts "Vive la France," and proceeds to skim the mountain's steep rocky slopes before flying perilously close to trees and boulders. He races by them at blinding speed. As the town of Chamonix nears, Dickinson safely pulls his chute.

"I have never seen any pilot go from basically unknown to 'wow' in such a short period of time," said Matt Gerdes, the cofounder of Squirrel, who has completed 1,200 BASE jumps, most of them in a wingsuit.

Dickinson flew steeper and faster, "the most daring lines that have ever been completed," Gerdes said. "He took it to another level that has not been matched by anyone else."

As his profile grew, veterans in the sport saw Dickinson's behaviour as excessively risky. Some sought to temper his jumps. Iiro Seppanen, president of the World Wingsuit League and retired from jumping, did so privately – and publicly.

In an October, 2015, Facebook post, Seppanen told Dickinson that he was "playing with very small margins … and it often comes with a price."

Then, last June, Dickinson lost one of his friends. Zanon, the pilot who filmed him at Le Brévent, died while flying alone. He was 33. Dickinson didn't jump for several weeks, but he was soon back at it. He couldn't stay away.

In July, he jumped from a helicopter in Rio de Janeiro to promote the Summer Olympics, along with Corliss and three other wingsuit pilots dressed in the five Olympics colours, for a fly-by of the Christ statue. In October, he starred in a World Wingsuit League competition at Tianmen Mountain in China.

Thereafter, he sought respite in Bali, in the small town of Ubud. Dickinson still struggled with Zanon's death. In a meditation class, when the teacher spoke of a higher consciousness and God, Dickinson couldn't reconcile the words. He struck an intense relationship with a woman but knew the pain of loss in his sport. One night, he told her: "I love you. But I can't do this to you."

In January, Dickinson returned to Tianmen Mountain to train and establish new jump locations. His spirits were strong. The day after his birthday, on his personal Facebook page, Dickinson wrote: "Life is perfect." A week later he would be standing on the doorstep of Heaven's Gate.

12 seconds

Rear-facing video captured Dickinson's jump as he attempted a flythrough of Heaven's Gate.

Two seconds into the jump, he's free-fallen about 20 metres and is moving at more than 50 kilometres an hour. Air blows through the inlets of his wingsuit and inflates it.

About four seconds in, the arch of Heaven's Gate is to his left and he has initiated the crucial element of his plan: an arc to the left of 180 degrees.

At about six seconds, the swooping turn complete, Dickinson straightens out his flight and aims toward the cave through the mountain. Just two seconds later, he would know he is dangerously low. He's already descended more than 100 metres and doesn't have much room left.

Ten seconds in, Dickinson enters the passageway. He is in full-flight, the equivalent of driving beyond the speed limit on the highway. Although he is an expert proximity pilot, he finds himself precariously close to the arch's jagged walls. The ground is coming up fast.

At 12 seconds into the flight, with no time to pull his chute, Dickinson hits the ground.

After Dickinson fails to check in as planned with a roommate, a series of calls among close friends and wingsuit pilots are made. The company that operates the Tianmen Mountain facilities, which had authorized Dickinson to jump in the area, is alerted the next day. A search party of 40 people is organized.

Dickinson's body is found after several hours of searching, not far from the statues of two unicorns and the top of a staircase of 999 steps, which tourists climb on the front side of Tianmen Mountain. The number nine is associated with the idea of eternity.

Back home in Ontario, an hour before sunrise, Dickinson's family gets the news.

Dickinson's journey

The sound of the air rushing by is a loud, cold rattle. Evan, watching rear-facing footage of his brother's final flight, shot by a GoPro camera mounted on Graham's helmet and recovered with his body, described the death as soul-crushing. Evan has lost about two dozen friends and acquaintances to crashes but the loss of his brother is like nothing else.

For weeks he struggled to sleep, hearing the sound of the wind of Graham's last moments.

"It broke me," Evan said.

Graham's death is logged as BFL-313 on what is called the BASE Fatality List, an unofficial tally of pilots and BASE jumpers who died on a flight or jump. Carl Boenish, the father of BASE jumping, is on the list, as is Canadian skier Shane McConkey.

In 2016, there were 37 BASE deaths, two-thirds of them wingsuit pilots. Last August, 15 people died – more than in a typical year a decade ago, as wingsuits and the attendant increased risk become more common.

Flying technique

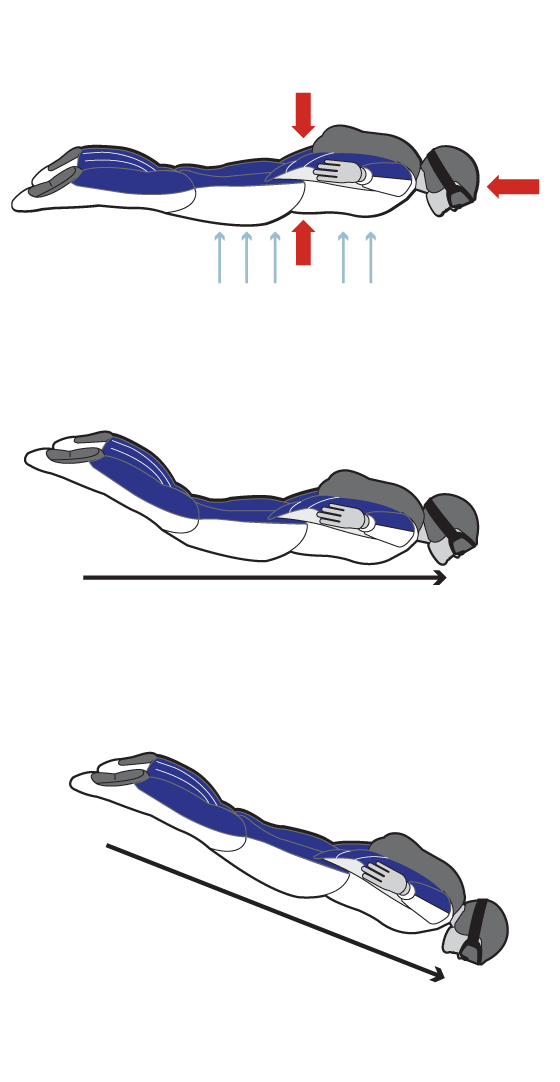

Wingsuit pilots use three forces: gravity, lift

and drag (air resistance).

GRAVITY

DRAG

AIR

LIFT

The conservative body position is flat, with

a slight curvature in the back. A cushion of air

supports the pilot, but there is limited forward

propulsion.

Tilting forward causes the air to propel the body

at a faster speed. The perfect angle, known

as the “sweet spot,” is unique to each pilot,

depending on their height, weight, suit design,

and, especially, their experience.

If the angle is too acute,

the gliding dive can get too

steep, causing the pilot to fall into

a real dive and lose altitude too quickly.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: NEWSWEEK

Flying technique

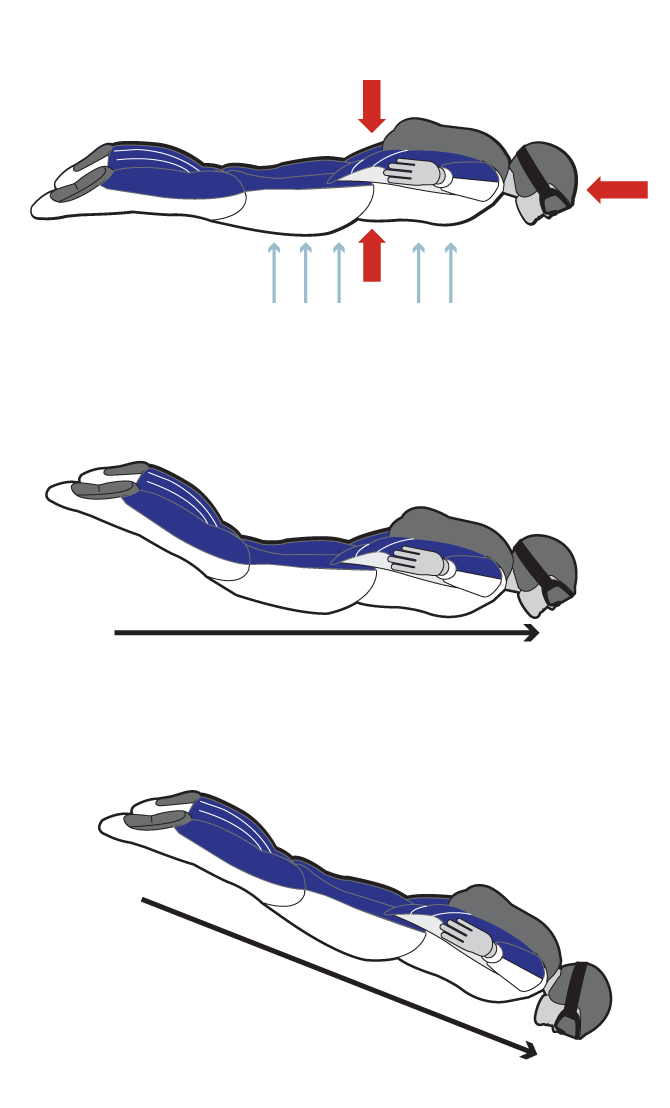

Wingsuit pilots use three forces: gravity, lift and drag

(air resistance).

GRAVITY

DRAG

AIR

LIFT

The conservative body position is flat, with a slight

curvature in the back. A cushion of air supports the pilot,

but there is limited forward propulsion.

Tilting forward causes the air to propel the body at a faster

speed. The perfect angle, known as the “sweet spot,”

is unique to each pilot, depending on their height, weight,

suit design, and, especially, their experience.

If the angle is too acute,

the gliding dive can get too

steep, causing the pilot to fall into

a real dive and lose altitude too quickly.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NEWSWEEK

18/18

16/16

13/13

Flying technique

Wingsuit pilots use three forces: gravity, lift and drag (air resistance).

GRAVITY

DRAG

AIR

LIFT

The conservative body position is flat, with a slight curvature in the back. A cushion

of air supports the pilot, but there is limited forward propulsion.

Tilting forward causes the air to propel the body at a faster speed. The perfect angle,

known as the “sweet spot,” is unique to each pilot, depending on their height, weight,

suit design, and, especially, their experience.

If the angle is too acute, the gliding dive can get too steep,

causing the pilot to fall into a real dive and lose altitude too quickly.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NEWSWEEK

Those close to Dickinson and the sport have different opinions on his final flight.

Seppanen, president of the wingsuit league, said: "He made a bad decision to attempt the impossible."

Evan said his brother wouldn't have jumped if he didn't believe he would be able to make it.

Gerdes said that while Dickinson's jump may not have been "obviously possible," Dickinson was experienced at Tianmen Mountain and in finding new jump locations.

In February, Dickinson's parents travelled from their home in Ottawa to Tianmen Mountain to stand where their youngest son jumped to his death. They saw where his body was found. They laid white roses and spread some of Graham's ashes.

After returning home, Norm spoke at a memorial gathering in Toronto. It was a celebration of life – but Norm and Pat wrestle with their emotions.

"We know that the pain will never go away but it will dull over time. We will carry the spirit and the memories," Norm said.

In an interview, he said, "It will definitely change us."

They knew it could end like this.

"You want your children to follow their passion," Norm said. "This was Graham's passion. His purpose. It was his journey."

MORE FROM THE GLOBE