The most revealing detail of the 1967 high-level ski traverse from Jasper to Lake Louise, which was going on 50 years ago this month, was that the Canadian perpetrators, upon finishing the unprecedented expedition, behaved as though it had never happened.

Twenty-one days, eight glaciers, countless peaks and 300 kilometres after they set off across a series of icefields and passes that had never before been traversed on skis, Chic Scott, Donnie Gardner, Charlie Locke and Neil Liske stepped out of the forest onto the Trans-Canada Highway near Sherbrooke Creek. Then they took their skis off and had a cup of coffee at Wapta Lodge. (Locke now owns it, and a couple of other ski resorts.)

Half an hour later, Locke and Scott were hitchhiking back to Jasper and Lake Louise, while Gardner and Liske had flagged a bus to Calgary. So much for heroics.

Ten years passed before anyone wrote the story up.

This extreme modesty turns out to be a key to the expedition's success – and to its meaning. It didn't matter that the four musketeers, as they called themselves, had managed one of the most daring ski routes ever attempted. What mattered was that they did it for reasons they didn't completely grasp, but which felt important regardless.

They wanted to find their own path, an unassailable sanctuary they could call their own.

They found it. Fifty years later, so has John Hartman. The acclaimed Canadian artist has painted a chronicle of the famous but until now unheralded trek.

The exhibit opened April 8 at the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies in Banff, and stays up until June 2. Painters have mostly ignored sports and the people who excel at them. But winning and losing, the clichéd currency of athletics, weren't a factor on the 1967 trip along the spine of the Rockies. That seems to have made all the difference.

The Whirlpool River and the Hooker Icefield, 2016, oil on linen, 48 x 68 inches.

Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

The first trip lasted 25 kilometres

People had been trying to ski the valley bottoms from Jasper to Lake Louise since 1930. But no one formally attempted the high-peak icefield route, along the treacherous glacier-ridden continental divide to the west of what is now the Icefields Parkway, until 1954, when Peter Bennett, a Toronto-based editor of the Simpsons-Sears department store catalogue, led an assault by a group of Southern Ontario ski mountaineers (there's an oxymoron). They made it 25 kilometres to their first camp, where they were engulfed by a storm that immediately made them call for mommy and turn back.

The next try – the one that inspired the successful 1967 attempt – took place in 1960. Hans Gmoser, the Austrian expatriate who came to the Canadian Rockies and, in the late 1960s, invented heli-skiing, had watched the 1954 attempt with keen interest. Gmoser had a classic Austrian love of preparation and hierarchy. By his decree, each member of his six-person party (average age 31) would carry a back-breaking 30-kilogram pack and wear metal Head Vector skis and staunch leather boots. Donnie Gardner, the son of Gmoser's doctor, watched the expedition set off. "Even at 14," Gardner remembers today, "I thought, they can't make that trip, that's too heavy."

Twelve days later, beset by weight and weather, Gmoser called it quits.

Gmoser was depressed by the mission's collapse. The turnaround represented not just the failure of a team, but of a way of conducting expeditions – that of the top-down, leader-oriented, guide-dependent approach to mountain expeditions beloved by the Swiss, Austrian and British climbers who dominated Canadian mountaineering for the first half of the 20th century, until the four musketeers came along.

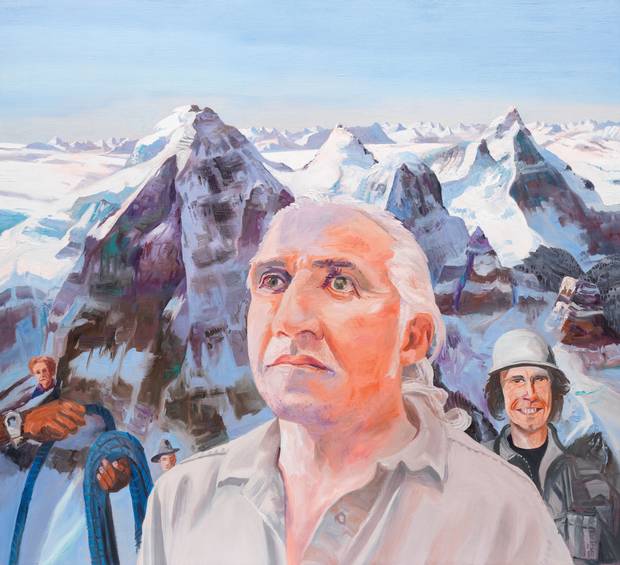

John Hartman, Barry Blanchard, the North Pillar of North Twin, 2015, oil on linen, 60 x 60 inches

Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

He couldn't have had better companions

Scott, Gardner, Locke and Liske took a lighter approach. Gmoser was a professional European outdoorsman who saw the mountains as an asset to be exploited. The pre-hippie lads who actually completed the traverse were Canadian amateurs for whom the Rockies represented a place of escape.

Chic Scott was an enthusiastic climber and a good enough golfer to consider turning pro. He had taken up cross-country skiing at the relatively advanced age of 17, and within a year was venturing into the mountains every weekend with Charlie Locke and Donnie Gardner.

He couldn't have had better companions. Locke was old Alberta: during the catastrophic winter of 1904-05, his grandfather, a homesteader, had had to kill and eat their only horse to stay alive. He grew up across the street from Gardner in Calgary. As boys they strung ropes from their bedrooms to a lamppost by the curb; they used the ropes to make Tyrolean traverses between each others' houses. Locke liked to say that he and Gardner had done "every first ascent of ever poplar tree on Sixth Street between Thirtieth and Thirty-second."

The fact that they were both still alive at 21 was a miracle. "We didn't know things couldn't be done," Locke told me recently. In the spring, as 10-year-olds, they liked to float down the flooding Elbow River on ice floes.

Gardner, another latecomer to cross-country skiing (he was 15), was religious about the alpine high country. "Donnie was spiritually more ahead of us," Chic Scott remembers. Gardner's hero was Knud Rasmussen, the Danish explorer who, in the early 1920s, was the first white man to traverse the Canadian Arctic from Baffin Island to Nome, Alaska, by dogsled, using traditional Inuit methods of survival. (He wanted to keep going, into Russia, but – this is true – his visa was refused.) In his forties, Gardner skied from Canmore, Alta., to the Pacific Ocean, alone, sleeping in a safety blanket in tree wells along the way, in 29 days.

In 1964, when they were still teenagers, Locke and Gardner made the second recorded winter traverse of Mount Rundle, along the famous slanted face that stretches nearly 20 kilometres between Banff to Canmore. Locke's feet froze, and to make the descent fast, the boys slid down the steep slopes of Rundle on their backsides – "hard-assing," they called it – setting off mini-avalanches as they went. The trick was to roll out of the way of the slide when you felt the pressure building on your back – and then roll back on when the wave had passed. The superintendent of Banff National Park was not impressed, but his dressing-down had zero effect. The following year Locke and Gardner traversed all 23 peaks that ring Lake Louise and Moraine Lake, an audacious feat on crumbling rock that has never been repeated.

By the fall of 1966, depressed by the steady rain at the University of British Columbia, Scott needed "a project." He wrote to Locke, suggesting they enact Gardner's obsession with a high-level Great Divide traverse from Jasper to Lake Louise the following spring, to celebrate Canada's 100th birthday. "It's taken quite a while," Scott wrote, "but at last I've convinced myself that my future is in the mountains and now I must begin doing a few things." Or, as he put it to me recently, "Everybody had a Centennial project back then."

They prepared over the winter, deciding on a team of four: that way, if someone got hurt, they'd be two teams of two. Eventually the threesome agreed on Neil Liske, a strong skier and ceramicist with whom Gardner had started climbing a year earlier. Liske was a little older – at 29, he edged the average age of the team to 22.5 years – but he and Gardner were the fittest of the four. On the slopes Locke and Scott brought up the rear at what fast skiers deride as "guide's pace."

Gardner insisted they travel light, and made radical choices for a long ski tour in inaccessible high country: thin featherweight wooden back-country touring skis with lignostone edges; light ankle-high touring boots; and nimble back-country cable bindings (great for going uphill, not at all great for crossing ice).

Gmoser openly opposed these decisions, especially the use of wooden skis. "You'll break a ski," he told Gardner before the trip, "and die."

Gardner even scorned climbing skins, the removable strips of artificial mohair that allow laden skiers to walk up steep slopes without sliding backward. No one today would attempt any traverse without them. But Gardner preferred ski wax. He approached the waxing of skis with the same reverence the Pope approaches Holy Communion. "It's a bit of an art," he says today. "I can't say it was always successful."

While Gardner arranged hardware, Locke planned the meals. To spare weight, he bought dehydrated dinners, a newfangled invention in those days, augmented with gorp (peanuts, raisins, chocolate chips, plus a few bars of fudge) for snacks and energy, and salami, cheese, and Gardner's mother's Logan bread for lunch ("It keeps you real regular, which is really important," Gardner told me, characteristically frank.) The total budget for the expedition was $3,665.

Unlike today's high-tech, thickly sponsored, endlessly ballyhooed expeditions, the 1967 traverse was an amateur production. The Canadian government hadn't published maps of the high country along the Continental Divide. Scott found the only guides available – some aerial photographs, and the boundary maps made by A.O. Wheeler between 1913 and 1925, when he surveyed the Alberta-B.C. border – and attached them to each other with brown packing tape, a detail Hartman records in his paintings of the trip. The team carried two sets, just in case someone fell down a crevasse.

They knew how to tie a prusik knot, which is useful if you want to climb a rope out of a crevasse, but only from reading books. "If we had gone down a crevasse or into an avalanche, we would have been hard pressed," Gardner says today. No one had taken an avalanche-safety course: they simply camped early, rather than cross huge slopes late in the day, when avalanches are most likely.

Their astonishing luck, and their faith in their luck, is part of what Hartman captures in the portraits and the paintings. But they never saw themselves as daredevils.

"The stuff people are doing now, I just find unbelievable," Gardner says. "I find it beyond reason."

Ideally, for Donnie Gardner, the most dangerous part of any trip is driving to and from the trailhead along the Trans-Canada Highway.

The team exhibited classic hard-headed, if somewhat questionable, Albertan practicality: they carried two ice axes (in case the route got steep and icy, in which case they could share), but only one avalanche shovel, which they could also share, provided it wasn't in the pack of the person buried. What they didn't have: avalanche beacons, avalanche probes, climbing harnesses, GPS units, cellphones. The only details they were sure about were the locations of their four food caches, which the lads placed themselves.

They set out on May 3, from the junction of the Whirlpool and Athabasca Rivers, not far from the town of Jasper, and skied across the Hooker Icefield. From there they dropped down into Fortress Lake; climbed up again onto the wild, remote Chaba Icefield; made their way to and across the Columbia Icefield; descended the Castleguard Glacier to the Castleguard and Alexandra Rivers; climbed the East Alexandra Glacier to the Lyell Icefield and the Mons Icefield beyond; slipped down to Forbes Brook and then up again onto the Freshfield Icefield; dropped down into the Blaeberry River valley, and rose up again onto the Wapta Icefield; and skied out to Sherbrooke Lake and the Trans-Canada Highway.

In words it is a short paragraph. But every leg would be a deadly expedition to an ordinary mortal. Gardner's biggest challenge wasn't the skiing, or the weight of his pack (a modest 45 pounds), but that fact that, mid-expedition, "I was supposed to have an interview for a job." Which is why, mid-trek, Gardner left the other three at the Alexandra River, south of the Columbia Icefield, skied out to the highway, and hitchhiked to Calgary, only to learn the interview had been delayed. Whereupon he hitchhiked and skied back into the mountains and was waiting for his pals when they arrived at Peyto Hut, a shelter on the Wapta Icefield.

The going was not always easy, despite the blithe spirits of the participants. The foursome were nailed for three days to an unnamed col between the Lyells and Mount Farbus as they waited out a storm. There were harrowingly steep headwalls to climb and descend, and crevasse-rippled glaciers to cross. But they never thought of the traverse as heroic. What really got them up and across and through was their patience, their willingness to let the terrain and the weather come at them, rather than bulling through.

Let me put that another way: they never took their luck for granted. Luck is the ultimate favour in the high mountains, where you live within their spell but at their mercy. It's something to be grateful for. The last time I spoke to Gardner, he had just returned from a trip to the forest, to cut some birch bark for an arthritic First Nation elder in Edmonton. Gardner had spent the morning sidling up to a tree he wanted to strip some bark from, never making direct eye contact with the birch, for fear of offending it or presuming its generosity: he stood still in the forest until he felt the tree had granted him permission to take some of its bark for his human purposes. The point isn't whether the tree can consciously grant that permission: the point is that Gardner took the time to observe the ritual, in case. In case is the Hail Mary of the backcountry skier.

Hartman had managed to catch this delicacy, too, in the way he depicts ski mountaineers co-existing gingerly within the immense power of the geography. It is as if they are always checking to see that they still have permission to be there.

Routes through the Rockies are often hard to discern – nothing looks as far away as it actually is – but there is nothing subtle about their isolation and their severity. Gardner lost 22 pounds on the trip. Each of the four food caches contained just enough food, fuel and ski wax for seven days, plus one of four extra skis they stashed (binding holes already drilled), in case someone broke one between caches. (They carried an aluminum replacement ski tip in their packs, in case.) They planned to be out for 35 days. They were home in 21.

"The gods were smiling on us," Chic Scott told me not long ago. "The gods looked down and said, 'They don't deserve it, but we'll let them live.'"

Fifty years later, Scott and Gardner still argue about how famous they should be for the Great Divide traverse. Scott describes the trip in glowing terms: "the Great Divide high-level traverse is possibly the greatest ski traverse in the world."

But when I reported that claim to Donnie Gardner a few days later, he scoffed. And then, being Donnie Gardner, he proceeded to expound about the exploit for 2 1/2 hours without interruption. They refuse to call their traverse a big deal, or anything much more than a romp in the mountains, even though they can't stop talking about it, half a century later. Hartman has captured that dilemma as well – the hard men who can't be hard men anymore, the old guys wearing new jackets, whose huge exploit is nevertheless dwarfed by time and the terrain in which it was accomplished. Mountains are big. Men are small.

Fifteen groups have completed the trek in the 50 years since, though it wasn't repeated until 1987. The only acknowledgment the foursome cared about came a few weeks after they finished, at a slide show Chic Scott and Charlie Locke gave to the Calgary Mountain Club. Hans Gmoser was in the audience. "Hans said one word," Scott remembers. "'Congratulations,' in his Austrian accent. And that was possibly the turning point, when the old European world became the Canadian world."

The Great Divide traverse marked the unofficial start of a new era in Canada's mountaineering history. "All of Canadian climbing before the 1960s was about Austrian and British climbing," Scott insists. Now local climbers were coming into their own. Today, Jim Elzinga, Barry Blanchard, Sharon Wood, Kevin Doyle and Diny Harrison – all of whom Hartman has painted in this series of portraits, posed in front of mountains of their subjects' choosing, often to commemorate where close friends died – are now famous in international mountaineering circles.

What I find most astonishing is that Chic Scott and his pals skied through one of the world's most intimidating mountain ranges completely out of contact with the outside world.

"Today people carry spot beacons and satellite phones," Scott told me. "You can be rescued almost anywhere, except maybe near the top of Mount Everest." All Scott and his pals had was a series of escape routes along the traverse. They were on their own in ways explorers on Earth never will be again. Hartman caught that lost daring, too.

John Hartman, Fortress Lake, 2016, oil on linen, 48 x 68 inches.

Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

Your goals in the mountains are achievable'

None of the four mountaineers who skied the first high-level traverse has travelled a straight path in the years since. Neil Liske is a successful ceramicist, but lives a private, some might even say reclusive life. Charlie Locke has weathered famous failures in his career as an owner of ski resorts. Chic Scott has had his struggles with depression, and Donnie Gardner has been afflicted by anxiety.

Their preferred medicine, in every case, has been the same: they head into the mountains for a walk in the woods in the winter. "Up there, everything becomes simple," Chic Scott says today. "Your goals in the mountains are achievable. There's a summit there, and you can reach it." Of course it depends how you get there.

"What's really interesting'" Don Gardner says, "is that none of us have followed a conventional path. It was our way of creating what a painter will paint, making what a maker will make, what a scientist will invent."

The mountains don't make it easy to get to know them, as John Hartman's compelling paintings make clear. But they are always there, waiting for us to try.

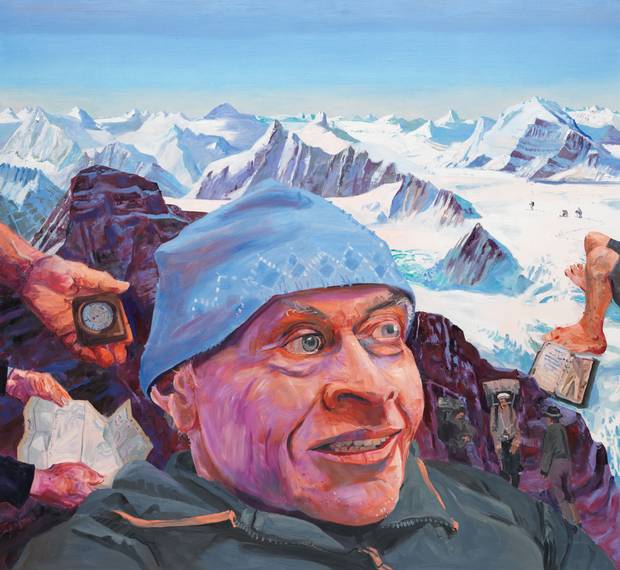

John Hartman, Don Gardner, The Hooker Icefield, 2015, oil on linen, 48 x 68 inches

Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies