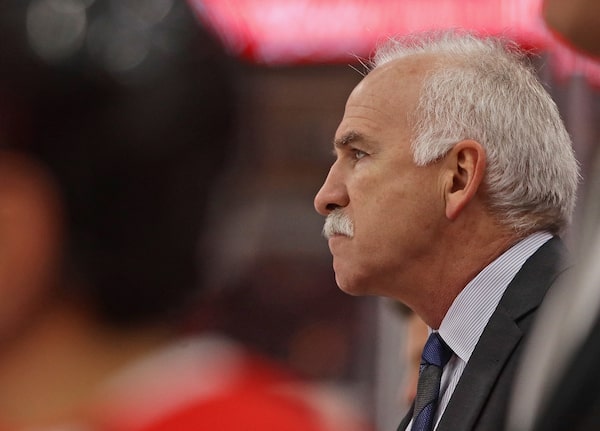

Then-head coach Joel Quenneville of the Chicago Blackhawks watches his team take on the Los Angeles Kings at the United Center in February, 2018 in Chicago.Jonathan Daniel/Getty Images

If a news dump is dropping a story you don’t want highlighted at the end of a busy day, what the NHL managed on Monday was a news tornado.

It was the first day of free agency. It was a holiday in Canada – the only place people care about free agency. It was the day that four of the five players in the world juniors sex-assault case were officially dropped by their teams.

Somewhere between Steven Stamkos getting dumped by the Tampa Bay Lightning for a younger version of himself and Nashville tooling up for a championship run, an e-mail was sent out by the league.

It concerned the three members of Chicago Blackhawks management exiled to hockey limbo after the Kyle Beach sex-assault civil case blew up in the league’s hands. The trio has spent two-and-a-half years being unpersons. Now they have been readmitted to paradise.

The headliner among them is Joel Quenneville. He was once regarded as the finest coach in the NHL, mostly because the Blackhawks had some really great drafts. All three are free to take work in the league again, but not right away.

They can only entertain employment offers after July 10th.

Front load the blowback. Back-end the real news. Clever.

Why now?

According to the league, it’s down to a trauma-informed word salad about “sincere remorse,” “greater awareness,” and “personal improvement” based on “myriad programs.”

Clear answers have been difficult to come by through this running disaster, but the questions never quit.

Like why, exactly, were they suspended in the first place?

The league is still hazy on that one. The best they can come up with is “an inadequate response” – though they were not the only people who knew about this, nor the only ones who should have done something about it.

How did the process in which they were suspended work?

No clue.

And reinstated?

Ditto.

The three men had different jobs with different responsibilities – head coach, general manager, and VP, hockey ops. Why did they all serve the same length of penalty?

Search me.

What’s changed institutionally?

You guess, then I will and we’ll both never know.

One known thing is that nearly 15 years ago, the Chicago brass got in a room right after a playoff game to discuss Beach’s accusation that he’d been sexually assaulted by the team’s video coach, Brad Aldrich.

When a law firm investigated the matter, everyone remembered that meeting differently. Some denied understanding what was said, others that anything substantive had been said at all. Quenneville’s memory was someone mentioning that “something may have happened,” but he didn’t know what.

I don’t know about you, but if the words “sex” or “assault” or any combination thereof popped up at an emergency work meeting, my internal radar would be pinging like a recess bell. But nobody in Chicago remembered anything.

As a result of their incompetence, Aldrich was allowed to leave of his own accord, with his Stanley Cup credentials intact. At one of his next positions, he was convicted of sexually assaulting a high-school student.

That is this story’s north star – that the men in charge of Blackhawks had a responsibility to their community, at which they failed egregiously, resulting in a preventable crime, because to do otherwise would have interfered with winning a playoff series.

Two-and-a-half years is a long time to be exiled from your professional tribe. There is no point to punishment without possibility of redemption. If they are contrite, it is right to consider their readmission. But not like this.

The NHL and NHL Players Association managed to pin this shabby incident on three guys who just didn’t want to hear about it. It helped that one of them was a household name.

Despite having been informed by Beach of what happened, the NHLPA pulled the trick of clearing itself on the file. A law firm it hired concluded that Beach’s accusations weren’t acted upon because of “a failure of communication.”

Another one? How do hockey teams manage to get to arenas on time every night? That also involves communication.

Standing above it all is commissioner Gary Bettman and the NHL command apparatus. In a well-run organization, the people on top are responsible for all institutional failures, including the ones they didn’t know anything about. Otherwise, “I didn’t know” becomes an excuse for every sort of administrative lapse.

If “I didn’t know” can work, no one will want to know anything, much less deal with it.

“I didn’t know” got the NHL into this mess. “I didn’t know” was the reason Aldrich was allowed to wander off in search of victims. And “I didn’t know” is how it’s ending – with zero explanation from the people ultimately in charge about how this went down, how the punishments were determined, and what steps have been taken to make sure it won’t happen again.

The only thing that has been accomplished is sin eating. Quenneville & Co. weren’t being paid these past two years, but they’ve had a lot on their plates.

The only consistent theme throughout has been cynicism. At every step, the first instincts of the people in positions of responsibility was avoidance. How could they kick this can onto someone else’s property, where it would become someone else’s problem?

You prevent this from happening again by embracing blame. Systemic failures are institutional opportunities. How did the institution fail and how can it get better? You can’t unmake history, but you can eliminate future excuses.

The way in which this ends – buried on the busiest news day of the year, strung out so that the eventual hirings will cause minimal problems, the investigative process opaque from start to finish – shows none of that has happened.

If I ran a hockey club, and I saw scandal headed my way, I’d know now what the NHL wants me to do – send someone else to that meeting, and make sure they never tell me what happened there.