The Flying Fathers were once called hockey’s answer to basketball’s Harlem Globetrotters.All photos by George Keily

“You can’t write this,” Father Vaughan Quinn says.

“If you do, I’ll have to kill you – and my sister will shoot me.”

Write what?

The Roman Catholic priest’s voice shrinks to a whisper.

“I just bought a new pair of goalie skates.”

Quinn is 84 years old. His most recent concussion – this one suffered in a fall rather than from getting slammed in the forehead by a hockey puck – led to a surgical procedure in which a shunt was inserted to relieve pressure on his brain. That left him with vertigo, which caused him recently to crash his bicycle. And yet he insists that he, unlike his fellow aging Flying Fathers, is not yet through with the game in which they delighted Canadians – though not always their bishops – for 46 years from 1963 to 2009, during which they raised more than $4-million for various charities.

This week, Eastern Ontario’s little Burnstown Publishing House released Holy Hockey: The Story of Canada’s Flying Fathers, a biography of the hockey-playing priests written by Frank Cosentino, who quarterbacked the Hamilton Tiger-Cats to two Grey Cups (1963 and 1965) and has now produced 18 books on various Canadian sports.

The Flying Fathers – the Chicago Tribune once called them hockey’s answer to basketball’s Harlem Globetrotters – began almost by accident in North Bay in 1963. The key organizer was Father Brian McKee, who had grown up in the little Northern Ontario city and excelled at sports, especially football. A shy, reserved young man, he turned to the priesthood despite having been offered a career with the CFL’s Winnipeg Blue Bombers.

The first team picture of The Flying Fathers.

While posted back to North Bay, McKee found one of his church’s altar boys had been clipped badly by a stick during a hockey match. There being no medicare in those days, the youngster’s family had not been able to afford the care the injured eye required.

McKee thought that if he organized a fundraiser, the required surgery could be arranged, and so he contacted various priests in the area that he knew played the game recreationally. The priests had no name – they would later choose between Puckster Priests and Flying Fathers – and they would play a local team in a fun match. They loosely scripted a few on-ice jokes, but for the most part played fairly seriously, defeating the locals 7-3 and surprising the fans who came out not even aware that the guys delivering the Sunday sermons could skate, let alone play.

When the local Catholic Youth Organization, of which McKee was in charge, found it couldn’t afford the rental fee for a hall in which the young people hoped to hold Friday night dances, McKee and a local disc jockey put together a second fundraiser where the priests would play a team put together by those working in local radio and television.

They had to get permission from the area bishop from the Diocese of Sault Ste. Marie, who was not convinced it was a good idea at all. Priests were to tend to their flocks, not tend nets. They were to take confession, not penalties.

Finally, the bishop reluctantly approved and on Feb. 20, 1964, the Flying Fathers met the Statics. A remarkable 3,126 fans turned out to cheer on the two teams, a crowd equal to any drawn by the local North Bay Trappers senior team.

The hockey was good, sometimes excellent, but the memories fans took away were far more often about antics. Slowly over time, the Flying Fathers developed skits to accompany their play. The first scorer from the other side would be given a special baptismal ceremony at centre ice ending with a pie in the face – a standard trick that often outraged the vain scorer while delighting the crowd. Various players would nip “altar wine” from a flask. A newborn baby would be hauled from a pileup.

‘Sister Mary Shooter’ makes a dazzling rush down the ice.

Then there was “Sister Mary Shooter,” played by a variety of players including Father Les Costello, who had won two Memorial Cups as a junior, a Stanley Cup with the Toronto Maple Leafs and had quit hockey at the age of 22 to become a priest. Costello, the team’s star player, would appear to have suffered a mysterious injury in a pileup and be carried, lifeless, to the dressing room – only to return quickly as “The Flying Nun,” dressed in full nun’s garb and gown and dazzling the crowd with end-to-end rushes.

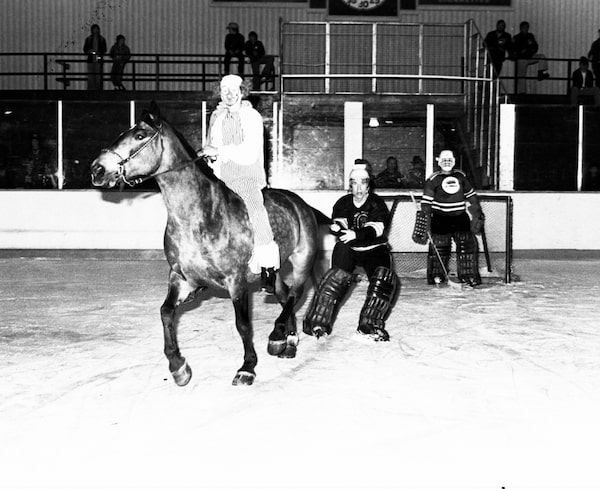

Then there was “Penance,” a horse the Smith brothers, Basil and Ernie, would hall from the family’s riding stables at Pinto Valley Ranch near Arnprior, Ont, The horse would be hidden from the crowd until, fully equipped, it was brought out onto the ice as a goalie substitute, Penance more often than not littering the ice with “road apples.”

The priests won that rematch 13-4, their play described by a North Bay Nugget sportswriter as “dazzling.” And why would it not be? McKee had lined up ex-NHLer Costello, Bill Scanlon and Pete Vallely who had played minor pro, as well as several top-notch former amateur players.

So successful was the fundraiser, that another match was called for. And this time, 5,030 showed up to cheer and laugh at the antics of the Flying Fathers. The game outdrew even an earlier exhibition match that put the NHL’s Detroit Red Wings against the local Trappers. Proceeds of $1,600 were turned over to cover the CYO hall rentals as well as a portion to the Children’s Aid Society.

’Penance’ the horse enters the game, not necessarily willingly, as the back-up goalie.

The Flying Fathers were now a team and would go on to play an average of 25 charity matches a year in its heyday. They had their own prayer and theme song (see bottom of this article). There were years when, as the Roman Catholic Church struggled, the fun-loving players, who bishops had been reluctant to okay, came to represent what was good and what was healthy about the priesthood.

“No question about it,” says Father Pat Blake, the team’s longest-serving player who, at 84, is now retired and living in Pembroke, Ont. “There were tough times, and we were seen as one of the good things.”

No one, it seemed, could prevent a smile from forming as they watched Costello and his antics. The former Leaf was a hyper-energetic, comedic delight both on and off the ice. He was such a magnificent skater that one of his “tricks” was to leap up onto the dasher boards back of the net, dance along the boards and then leap back down to the ice having avoided a check. “Million-dollar legs and a 10-cent mind,” his younger brother Murray, who would go on to become president of the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (later Hockey Canada) says with affection.

No question about it, there were tough times, and we were seen as one of the good things.

— Father Pat Blake, the team’s longest-serving player.

The beloved “Father Les” appeared lost to the team after an ill-fated expedition in the fall of 1979, when he somehow got lost while hunting partridge in the Northern Ontario woods near his parish in the small mining town of Schumacher. He lost a boot in a bog, with night and the temperature falling, and no one then searching for him. He shot a partridge and wrapped its carcass around his foot for warmth, but it was not enough. By the time he was found, frostbite had turned his feet black and seven toes had to be amputated.

They said he would never walk again.

Ever the comic – Costello always showered in his underwear because he said the church had taught him “never to look down on the unemployed” – he took to calling his three remaining toes “Father, Son and Holy Ghost.” Ever the optimist, he determined that he would not only walk, as doctors had doubted, but he would again skate.

“He got the key to the arena,” Murray Costello remembers. “And he did it all alone, at first walking around the ice holding onto the boards until he finally took a first stride. He fell, but he got right back up again and he kept at it.”

He would skate, and play, again, but was never the same.

“Before he lost his toes, he could do anything,” Blake remembers.

“The Flying Fathers kept my brother alive,” Murray Costello says. “He could not sit still for 10 seconds. He needed to let all that energy out. He’d die if he just sat in his parish and did nothing.”

Father Les Costello, right, with Jim Farelli, coach of the Pembroke Lumber Kings.

Les Costello played for the fathers for another 23 years, until a puck struck him hard in a charity match played in Kincardine, Ont., and he fell to ice, striking his head hard. He never woke from the blow, falling into a coma and dying in hospital on Dec. 10, 2002. Rather appropriately, his funeral had to be moved from his Catholic church in Schumacher to the arena to hold the more than 2,000 mourners.

If Father Les Costello had been the Flying Fathers’ first great character, there was no doubt who was the next: Father Vaughan Quinn.

Quinn had been born into affluence in Montreal, the son of a successful doctor. A small, scrappy leprechaun with a foul mouth and a wild sense of humour, Quinn had cared only for hockey, football and boxing while growing up. He flunked out of medical school, decided to become a priest and drove his Cadillac convertible across the Quebec-Ontario boundary to Arnprior, where he would spend the next seven years studying with the Oblates of Mary Immaculate to become a priest.

Quinn was sent to serve in Ottawa, where soon he was the one being served – beer, whiskey, rum, whatever he could get his hands and lips on. He was drunk at mass. He passed out hearing confessionals. One year after he got his collar, he would be escorted by a church official to Chicago where he was institutionalized until he dried out.

He has been a member of Alcoholics Anonymous “since June 16, 1963,” he says.

Quinn says he agreed to go to AA meetings because that was the only way he could get out of the rehabilitation centre. Sent to Detroit, where he lived at a Sacred Heart rehab centre and worked with the homeless, he found great success and recognition, in no small part because of his eccentric ways and tough-love attitude. He picked up drunks in an old hearse, brought them to the centre and dried them out. “If someone brought a bottle in,” he says in the no-nonsense language he prefers, “I’d kick the living shit out of them.” He figures he took as many as 1,500 men a year off the street and got most of them back working. His younger sister, Martha, joined him in the work.

Every Wednesday, Quinn would cross over to Windsor, where he played goal for a local recreational team.

“The Flying Fathers were coming to Windsor,” he recalls, “and I get a call. ‘We need a goaltender.’ I knew nothing about the Flying Fathers. I show up and no one tells me anything. The goddamn horse is in the shower! They had to hide him from the audience, so that’s where they put him.”

Quinn and Penance the horse became a team of another sort. Penance would leave a “sampling” on the ice and the little goalie would have a shovel handy. He’d scoop up the manure and skate as if he were diligently cleaning up the mess, only to toss the shovelful at one of the opposition players. Some laughed. Some, like a well-known broadcaster in one Canadian city and the local police chief in another, were outraged and let the goalie know. He laughed in their faces.

“I threw it every time,” he cackles. “I didn’t care who it was.”

Quinn would sometimes climb onto the top of his net and pretend to be napping when play was in the other end. He was so lax with his mask that it sometimes cost him. “I got 17 stitches here,” he says, tracing a finger along one cheek, then switching to the other side of his face. “And I don’t know how many here.”

Quinn was so irascible, he sometimes brought unwished-for attention to the team. At a charity event in Anchorage, Alaska, sponsored by Wonder Bread, he and Father Les did a television interview in which one of them asked the female interviewer, “Is it true that your buns are flown in fresh each morning?”

Quinn swears the crack was Costello’s. Blake says there is no doubt in his mind that it was Quinn. No matter, the Bishop in Anchorage heard it and demanded they present themselves to him.

“If he wants to see us,” Costello responded, “he can come to the game.”

An ‘ordination’ ceremony is held on the ice.

For nearly five decades, the Flying Fathers were a celebrated success in Canada. They played in Europe and in parts of the United States. Peanuts creator Charles Schulz once got the pie in the face and enjoyed it so much, he asked for a second.

So popular and famous were the hockey-playing priests at one point that Hollywood took notice. In 1981, the NBC reality-television program Real People did a feature on the team and, almost immediately, team captain Father Tim Shea found himself fielding calls from big-time producers, including Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios.

The studio dispatched an emissary who spent weeks following the team and an offer was made to buy the rights to the Flying Fathers’ story, as only Hollywood could tell it.

“They wanted to jazz it up,” Blake remembers.

“They had me getting drunk all the time and the boys having to go and find me and sober me up for the game,” Quinn adds. “They wanted sex in it, so they had some of the boys chasing girls.”

The Flying Fathers turned Coppola down.

Father Pat Blake and Father Les Costello take a break from the game.

Gradually, the score clock caught up to the team. Some, such as McKee and Costello, passed on. Some lost the ability to play well. Blake had knee surgery five years ago and skated last year for what he says was the last time.

The Flying Fathers were fading away. “Our ‘farm club’ wasn’t producing,” Blake says. “There was nobody to take up our places. There was one attempt by a group of priests last year to start up a new team. They can use the name. We wish them well.”

As for the possibility of 84-year-old Father Vaughan Quinn and his new goalie skates taking up a spot in the crease of any new version of the Flying Fathers, Blake just shakes his head and laughs.

“I think he’s dreaming,” he says. But that, of course, is how the whole remarkable story of the Flying Fathers began in the first place.

The Flying Fathers Prayer

Help me God to do your will

As I pass through this life …

Praying and playing for a better world.

Each part complements the

other and both are essential if I

am to fulfill that purpose.

All of us have been given talents,

abilities, and inner resources. May

we use these gifts well.

Your rules are my guiding

light. May I remember my

position on your team, God,

Today and Always.

The Flying Fathers’ Theme Song

We come from many places

All across this great land

Whenever there’s a need

To lend a helping hand

And we came together

As if by some decree

We became the Flying Fathers

And we go from sea to sea.

Refrain:

We play the game of hockey

And prove to everyone

That you can still have religion

And still can have some fun.

We’re playing and we’re praying

And we’re doing what we should

Even when we give out checks

We give out brotherhood.

We usually win most every game

Though sometimes it looks fixed

With cream pies, buying off the refs

And tricky hockey sticks.

We always try to pull a stunt

To score the winning goals

And even when we lose the game

We still have won some souls.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Lou Farelli in a picture with Father Les Costello. It has since been corrected to identify the man as Jim Farelli, coach of the Pembroke Lumber Kings.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story had an incorrect name for the parish of Father Les Costello. The town and parish is in fact called Schumacher.