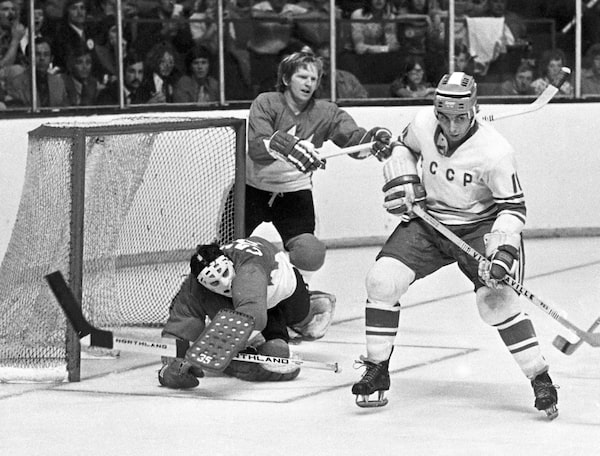

Team Canada goaltender Tony Esposito covers the net behind Team USSR's Eugeny Zimin as Pat Stapleton looks on during the 1972 Summit Series in Toronto on Sept. 4, 1972.Peter Bregg/The Canadian Press

When Gary J. Smith began writing his entertaining behind-the-scenes history of the Summit Series, the iconic 1972 clash between the Canadian and Soviet Union men’s national hockey teams, there was no way he could have foreseen how relevant the book might be upon its publication this month. Almost eerily so: On the very day Ice War Diplomat: Hockey Meets Cold War Politics at the 1972 Summit Series was shipped to the printer in late February, Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered his troops to invade Ukraine. In an instant, Ukraine was in chaos and Russia was again a pariah.

And yet, as Smith noted in a hastily rewritten conclusion, the current situation is not “unlike what Pierre Elliott Trudeau faced in the early 1970s when dealing with a nuclear-armed hostile power following the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.”

“Forty to fifty books have been written about the Summit Series,” Smith, 77, suggested this week, during a phone interview from his home in Perth, Ont. “And I’d say almost all of them didn’t get into the diplomatic and the political side of things.”

But while the series may have been received by the Canadian and Russian people as a delirious sports spectacle, Smith makes clear its genesis was pure realpolitik. Hockey was seen as a bridge between two countries. And in Canada’s case, at least, the construction orders came from the very top.

He begins the tale as a newly married, 23-year-old poli-sci grad who moved to Ottawa to join External Affairs in the spring of 1968, just as the “hip new philosopher Prime Minister” is intoxicating the citizenry with the prospect of taking Canada to a larger role on the world stage. Trudeau, who believed in the importance of sport and culture as national unifiers, had made both of them planks in his election platform.

Smith and his wife, Laurielle, spent a year immersed in Russian-language lessons, learning the country’s history, and hoovering up Chekhov, Tolstoy, Tchaikovsky, and Rachmaninoff. Then, in early 1971, they moved to Moscow, where he was posted as a junior political officer, setting him up to help create what would become the most famous example of sports diplomacy in Canadian history.

That spring, Trudeau became the first Canadian prime minister to visit the Soviet Union. He had multiple agendas: not just containment of a nuclear power, but also to give Canada what he termed some “breathing room” from the United States and President Richard Nixon. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union was feeling pressure to find its own allies, especially after the United States and China – the Soviets’ other primary adversary – began engaging in “Ping-Pong diplomacy.”

And Trudeau, who was frustrated that pros were barred from participating in the Olympics and other international competitions, wanted to find a way to show off what he believed was the superiority of Canadian hockey. So when the Prime Minister showed up in Moscow in May, 1971, hockey was, according to Smith, sixth on the list of priorities. Later that year, when Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin visited Canada, he and Trudeau signed a General Exchanges Agreement that included references to an “exchange of sportsmen.”

Smith offers readers a portrait of Soviet hockey culture in the early 1970s, as well as a sense of what the players themselves were like, a perspective gained from his unusual role as the Soviet team’s translator and fixer during their time in Canada during the first four games of the series.

He also offers humorous glimpses of the realities of consular responsibilities, including the estimates that he and his colleagues gamed out on how many rowdy visiting Canadians they expected would be arrested for disorderly conduct during the Moscow leg of the series. (Smith and his colleagues also struck deals with the authorities for them to go easy on the visitors, who might be too inclined to enjoy the very good and very inexpensive domestic vodka.)

And he recalls the effect that a centre-ice pratfall by Phil Esposito, during the opening ceremony of Game 5, had on the locals. “The way he reacted brought smiles to their faces, and it showed the Russians that we are different cats: You know, we’ve got long hair, we’re individualistic, falling down is not going to end someone’s career or somebody’s life,” – as, it was believed in the West, it might have if a Soviet player had similarly embarrassed himself or his team. “To the extent that sport can provide those moments of humanity, it’s a good thing.”

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine and alleged war crimes playing out across our screens every hour, 1972 can seem innocent by comparison. But as Smith notes, “We did have a nuclear faceoff. It was a communist regime trying to spread communism around the world.”

Smith spent his life as a diplomat, including stretches in the 1980s working as the director of the Arms Control and Disarmament Division of External Affairs. Can he actually envision a future in which Canada engages Russia with sports diplomacy?

“It’s a good question,” he admits. Right now, he says, he’s watching the situation with the Russian players in the NHL. After some initial consternation – especially toward Alexander Ovechkin, who is “with Team Putin,” Smith notes the Russian players “are still rolling along. And so I’m watching to see whether the public are going to demand that their contracts be terminated or not. Are we just going to say, all right, we like them, they’re not responsible?” If so, he says, then what he calls the “hockey bridge” is still intact.

“What we want to know is whether each one of those players is communicating back to Russia what’s really happening here. Are they transmission belts for the truth? If so, that would be good.”

“Today, we’ve got a war that’s ongoing, which clouds the situation. But, you know, Russia is not disappearing from this Earth. At some point, we’re going to have to re-engage with them.” If only to ensure, as he says, “their nukes don’t go off.”