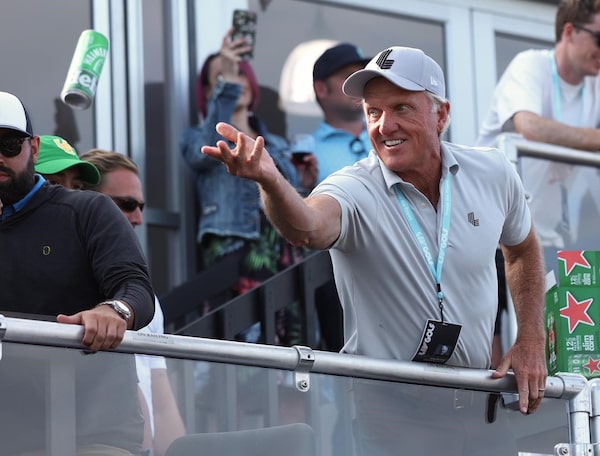

Greg Norman tosses a beer into the crowd during the Portland Invitational LIV Golf tournament, in North Plains, Ore., on July 2.The Canadian Press

It was only this spring that Greg Norman, who twice hoisted the claret jug as the winner of the British Open, sought a special dispensation to play in this week’s tournament at St. Andrews in Scotland.

The reply was unequivocal: No.

And not only is there no spot in the field for Norman, whose role in the new LIV Golf series has made him a pariah in certain golf circles, but it turns out that Norman is not even invited to dinner.

The R&A, which organizes the Open, over the weekend became the latest corner of golf to say it had cast Norman into exile, temporarily banishing him even from the traditional dinnertime gathering of past Open champions. The move has made this week’s tournament, the last of the year’s four golf majors, the newest flash point as players and executives openly clash over LIV Golf, the Saudi-funded insurgent league that has made a sport that Norman once ruled decidedly factional.

In a polite-but-firm statement, the R&A made clear it had chosen a side. It had contacted Norman, it said, “to advise him that we decided not to invite him to attend on this occasion.”

“The 150th Open is an extremely important milestone for golf and we want to ensure that the focus remains on celebrating the championship and its heritage,” the R&A said. “Unfortunately, we do not believe that would be the case if Greg were to attend. We hope that when circumstances allow Greg will be able to attend again in future.”

LIV Golf, whose main financial backer is Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, did not respond to a request for comment. But Norman, LIV’s CEO, told Australian Golf Digest that he was “disappointed” and thought the decision was “petty.”

“I would have thought the R&A would have stayed above it all given their position in world golf,” said Norman, whose lone victories in major tournaments came at the Opens in 1986 at Turnberry and in 1993 at Royal St. George’s.

The public tangle between Norman, 67, and the R&A began in April when he expressed confidence in the Australian news media that he could receive an exemption from Open rules – which allow past champions to enter on that qualification alone if they are 60 or younger – and play in the 150th iteration of the tournament, scheduled to begin Thursday at the Old Course in St. Andrews, Scotland.

Word soon came back that the R&A would offer Norman no such exemption. (The governing body has flexibility: It agreed to admit Mark Calcavecchia, the 62-year-old professional who won at Royal Troon in 1989, because the Open that was expected to be his farewell in 2020 was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic and he was recovering from surgery last summer.)

But attention on – and scrutiny of – Norman has only increased in the interceding months, as he has lured past major champions such as Dustin Johnson, Phil Mickelson and Patrick Reed to the LIV series, rupturing their ties to the PGA Tour and turning golf into a cauldron of acrimony. His statements in May dismissing Saudi Arabia’s murder and dismemberment of a Washington Post journalist by saying, “Look, we’ve all made mistakes,” prompted new criticism.

Asked Monday about the R&A’s decision to exclude Norman, Jack Nicklaus, who won the Open three times, demurred.

But even as Nicklaus, who is scheduled to become an honorary citizen of St. Andrews on Tuesday, hailed Norman as “an icon in the game of golf,” he stayed well away from supporting Norman’s new tour.

“We’ve been friends for a long time, and regardless of what happens, he’s going to remain a friend,” Nicklaus said. “Unfortunately, he and I just don’t see eye to eye in what’s going on. I’ll basically leave it at that.”

Norman is not the first major champion to miss a gathering of past winners this year because of a furor tied to Saudi Arabia. Mickelson, a three-time Masters champion, was absent from the event at Augusta National Golf Club in April after he condemned Saudi Arabia’s “horrible record on human rights” but said LIV was “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reshape how the PGA Tour operates.”

Mickelson is expected to play at St. Andrews this week.