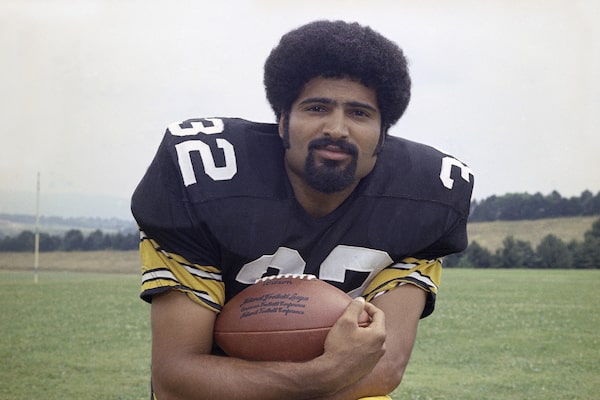

Pittsburgh Steelers running back Franco Harris in 1973.Harry Cabluck/The Associated Press

There are heroes aplenty in Southwestern Pennsylvania. Andrew Carnegie, who built a steel empire, created a string of public libraries and lent his name to a great university. Andy Warhol, who made contemporary art pop. Jimmy Stewart, who brought morality to the silver screen. Gene Kelly, who danced his way into the hearts of millions. Fred Rogers, who made youngsters worldwide feel as though they lived in his neighbourhood. Christina Aguilera, the singer sometimes known as the “voice of a generation.” The hundreds of thousands of steelworkers and coal miners – their names unknown, their toil indispensable – whose overtime work in fiery mills and dank and dark mines helped create the arms that won two World Wars.

But there is no hero here with the exception of Roberto Clemente – no politician, no performer, no icon of philanthropy – revered remotely as deeply as Franco Harris, the Pittsburgh Steelers running back forever identified with the 1972 “Immaculate Reception,” the consensus greatest moment in NFL history.

And so when Harris died at age 72 Wednesday – three days before his jersey, No. 32, was to be retired – Pittsburgh skipped a breath, maybe two. A university dean paused in his morning workout. A bank president searched for answers. Members of the clergy said prayers. “We had to,” Bishop David Zubik, who earlier had been bishop of Green Bay, said in an interview. “We had to thank God for his example and for helping all of us see his lessons on how to be humble.”

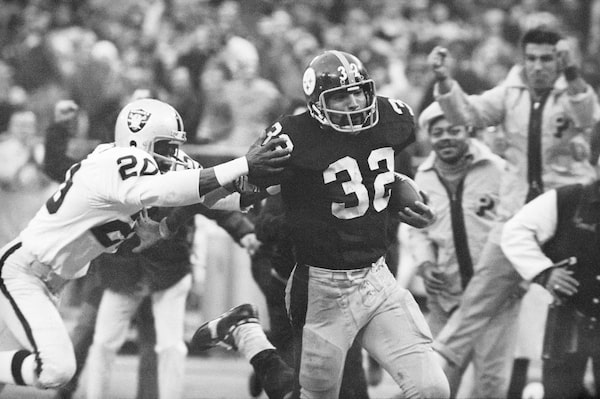

Harris eludes a tackle by Oakland Raiders' Jimmy Warren as he runs 42-yards for a touchdown after catching a deflected pass during an AFC Divisional NFL football playoff game in Pittsburgh on Dec. 23, 1972.Harry Cabluck/The Associated Press

The word “tragedy” was tossed around like a pigskin in a pregame warm-up. Three grown men I spoke with – accomplished, stoic in their professional lives – fought back tears. And when I telephoned the former mayor of Pittsburgh, he picked up the phone and, not knowing the reason for the call, answered not with a “hello” or a greeting but simply with one word:

“Heartbroken.”

When Maurice Richard, the francophone hero of Quebec and the hockey-playing squire of the Montreal Forum, died in 2000, Cardinal Jean-Claude Turcotte, archbishop of Montreal, told mourners gathered in Notre-Dame Basilica – including prime ministers and provincial premiers – that the greatest of the great Canadiens “was an intense man, passionate, true to his values and convictions,” adding, “His passing was felt by people across the country. It was like losing a friend.”

Those very words apply to Harris, who will be forever remembered in the black and gold of the Steelers and in the blue and white of Penn State University in the way that Richard is remembered in the bleu, blanc, rouge of the Canadiens.

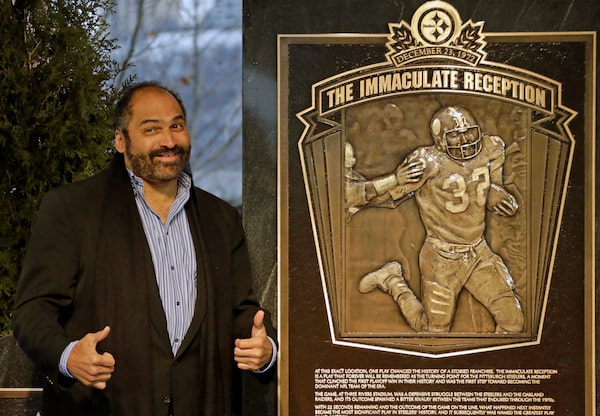

Harris twirls a Terrible Towel during a ceremony commemorating the 40th anniversary of the 'Immaculate Reception' in Pittsburgh, Dec. 23, 2012.Gene J. Puskar/The Associated Press

Except that Harris – son of an African-American father and an Italian mother – is an icon not only in Beaver Stadium at Penn State, or Acrisure Stadium in Pittsburgh but also at Pittsburgh International Airport. There, a statue of Harris stands beside a statue of George Washington. Every day scores of people have their picture taken beside the Franco Harris statue. No one asks for a picture beside the father of the country, dispatched here in 1753 to confront the French and assert the British claim on the area around the three rivers.

“The two 21-year-olds who made history in Pittsburgh stand together,” said Andrew Masich, the president of the Heinz History Center who conceived of the exhibit and who was with Harris the day before he died. “But so many people are leaving Franco reminiscences that today the statue had to be moved.”

It was at Three Rivers Stadium that Harris sculpted his masterpiece, the Pittsburgh sporting bookend to Bill Mazeroski’s walk-off home run against the reviled New York Yankees to win the 1960 World Series.

It occurred 50 years ago Friday, during an AFC divisional playoff game against the Oakland Raiders. The Steelers were trailing, 7-6, on fourth down with 22 seconds left. Quarterback Terry Bradshaw lifted a desperate pass in the direction of John Fuqua, who was bumped by the Raiders’ Jack Tatum, the deflection from the collision sending the ball into the air and into the hands of Harris, who grabbed it before it hit the ground and galloped into the end zone to give the home team a 13-7 victory.

In retirement Harris was a ubiquitous presence in Pittsburgh. “He was a star on the football field,” said Rabbi Jamie Gibson, who encountered him at meetings throughout the city, “but a true giant in the civic life of this community.” William Peduto, a two-term mayor of Pittsburgh, at age eight had chosen Harris as his hero, only to conclude at age 58 that Harris was an even larger figure once his Steeler days were over. “I can’t recall once him asking for anything,” said Peduto, fighting back tears. “And whenever anybody asked for something from him, he always said ‘yes.’ Most of the time there was never a reporter or camera there. He quietly and constantly gave of himself.”

Harris on the spot of the 'Immaculate Reception' after a marker commemorating the 40th anniversary.Gene J. Puskar/The Associated Press

Harris shaped childhoods across the border. “He was my boyhood idol,” said Anastasios Roussopoulos, general manager of the Petros restaurant in Montreal, who now drives the 975 kilometres to Pittsburgh four or five times a year to attend games. “He helped make me a Steeler fan forever.”

Art Rooney II, president of the Steelers, is not known for florid rhetoric nor for tugging at emotional heartstrings. But Wednesday morning the words flowed. “His impact was so enormous on the franchise, the whole city and, really, people around the world,” he told me. “He brought joy and happiness everywhere he went.”

Harris had his detractors, to be sure, growing out of his defence of his Penn State coach, Joe Paterno, fired for failing to address the child abuse of assistant coach Jerry Sandusky. “No one supported Joe the way Franco did,” said Lou Prato, considered the unofficial historian of Penn State sports. “He was there on his doorstep for Joe.”

The wounds from that episode are still raw. Two members of the Penn State board of trustees asked not to be interviewed when contacted Wednesday. No one else hesitated.

“I’ve waited on him for years and he always did something most people don’t do – give you eye contact,” said Debra Weiss, a catering associate who served Harris earlier this month at a fundraiser at the home of Steelers coach Mike Tomlin. “He never passed up an appetizer.”

One thing more: He made every cocktail party an Immaculate Reception.

David Shribman

David Shribman