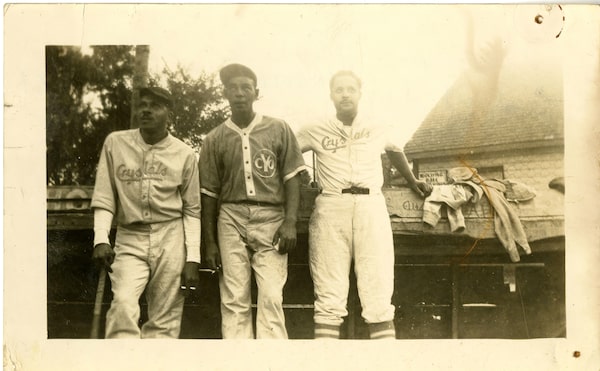

Fergie Jenkins, Sr, Andy Harding, and Ross Talbot in Crystals and CYO uniforms.Courtesy of the University of Windsor, Archives and Special Collections/Supplied

When Heidi L.M. Jacobs thinks about the history of Black baseball in Canada, what comes to her mind are those weather maps you see on U.S. TV, the ones where each of the states is colourfully delineated and Canada is just a big blank space. “It’s like, ‘There’s no weather in Canada – all the cold and warm fronts just stop at the border,’” Ms. Jacobs said with a laugh the other day.

That’s what happens when the United States takes up so much narrative oxygen with its stories – all the more so with a sport that is as conscious about using its history for mythmaking as baseball.

In recent years, the sport has worked to try reconciling with its racist past by shining a belated spotlight on the Negro Leagues, the assortment of associations that provided most of the opportunities for Black players in the United States before Jackie Robinson broke the modern-day major-league colour barrier in 1947. But while those efforts are important, they unintentionally obscure Canada’s own rich – and fraught – history of Black baseball.

One of the best known of those Canadian stories is of the Chatham Coloured All-Stars and their emergence in 1934, seemingly out of nowhere, to win the Ontario Baseball Amateur Association championship (Intermediate B division).

Their fame has grown recently, but Ms. Jacobs is the first author to produce a comprehensive account of both the triumphs and tribulations of the team, and the men themselves – their families, communities, and lives before and after baseball. Her 1934: The Chatham Coloured All-Stars’ Barrier-Breaking Year slid into bookstores earlier this month. (Royalties from the sale of the book will go toward the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society.)

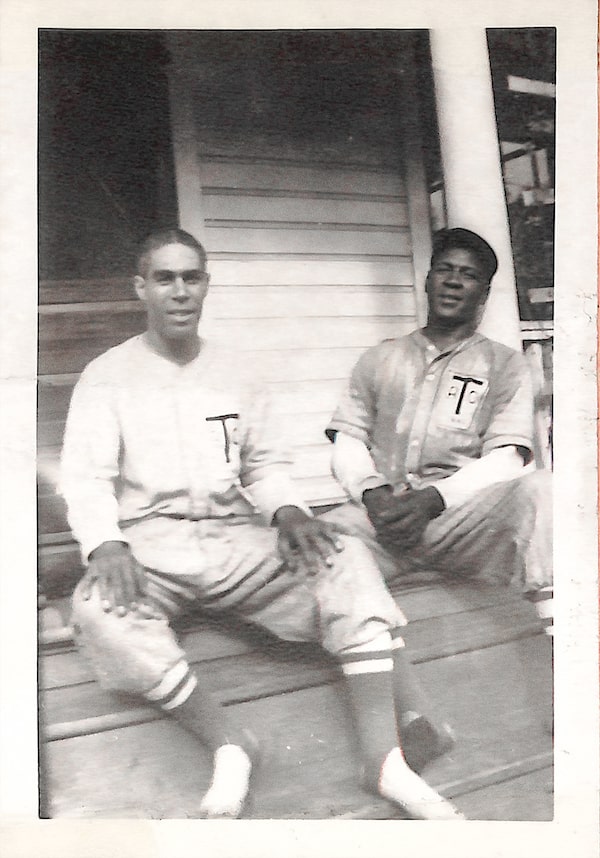

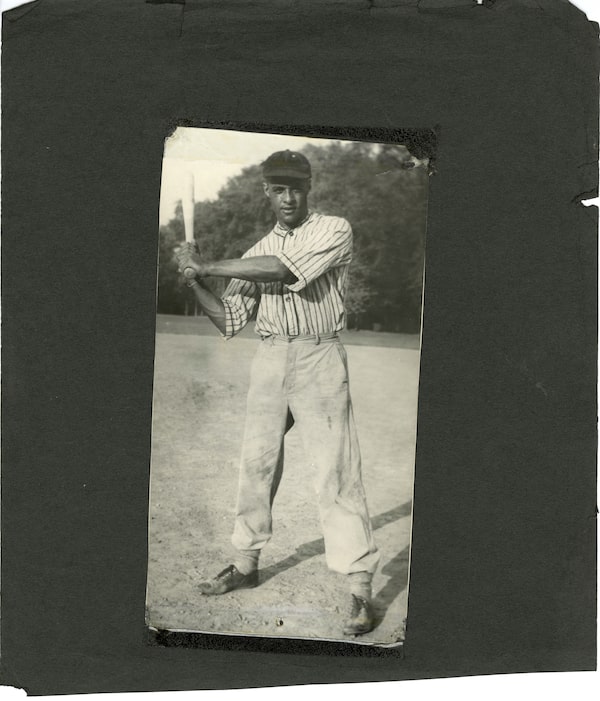

In those pages, readers will meet Wilfred (Boomer) Harding, a stellar first baseman who joined the All-Stars as a teenager and played with them for seven years; Earl (Flat) Chase, a pitcher with a wicked arm and gifted spray hitter who could clobber titanic home runs as easily as tying his shoes; the acrobatic third baseman, Kingsley Terrell; and Donald Tabron, a street-savvy teenaged import from Detroit who had overseen the gambling activities at his family’s rent parties and was eager for a change of scenery. They will also hear mention of an occasional substitute player with the last name Jenkins, who was almost certainly Ferguson Jenkins, Sr., who officially became part of the team in 1935.

King Terrell and Flat Chase in Taylor ACs uniform.Courtesy of the Chase family/Supplied

Wilfred 'Boomer' Harding.Courtesy of the Milburn family/Supplied

There, too, readers will learn about the peculiar history of Chatham and its place in the Underground Railroad, the racism that Black residents endured, the advocacy of one 19-year-old sports reporter for the white townsfolk to embrace the team as their own, and the bid for respect that playing baseball represented.

The book got its start in 2015, when Pat Harding, Boomer’s daughter-in-law, gave three oversized binders stuffed with photographs, newspaper clippings and other materials to one of Ms. Jacobs’s colleagues at the University of Windsor, and asked whether they might be interested in digitizing the ephemera. Two years later, they launched a website, Breaking the Colour Barrier, which included images from Ms. Harding’s scrapbook and others, a collection of archival and new audio interviews, and other memorabilia.

Those All-Stars scrapbooks, which were often begun and nurtured by the mothers of players, might just as easily have ended up staying in a dusty attic.

“I think the story is important, because it makes us do two things: It acknowledges the racialized history of sport in this region and in Canada. But I hope it also makes people think what other stories are out there,” said Ms. Jacobs, who is both an award-winning author (her debut novel, Molly of the Mall: Literary Lass & Purveyor of Fine Footwear earned the 2020 Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour) and a digital scholarship librarian with the University of Windsor.

Ms. Jacobs mentions an anecdote with which she starts the book, about frequently taking the train through Chatham and passing Stirling Park, the downtown slice of green that had been the home field of the All-Stars. Until she had begun working on the book, she hadn’t noticed the park because it was obscured from the train by a stand of trees.

“It’s kind of a nice metaphor. Like, what are the other things that we walk by or ride by or drive by every day, and we don’t know the history there? So, I’m hoping that this story is sort of a spark for other people to look into stories – if they’ve got stories in their attics, basements, communities, neighbourhoods – that those stories can start to come out, to again change what we think about Canadian history.”

The scrapbooks enabled Ms. Jacobs to bring the All-Stars’ history to life, and pointed her to stories she almost certainly would have missed if she were working solely from microfiche.

She mentions one story she stumbled upon through a clipping in a scrapbook started by the mother of Flat Chase. The Chatham Daily News published a letter to the editor signed by someone calling themselves “A Coloured Fan,” taking issue with a sports columnist’s criticism of the allegedly rough play of the All-Stars.

Written with satiric tartness, the letter brims with resentment over the racist behaviour of an opposing team, from Strathroy, Ont., and their fans, who “subjected [the All-Stars] to a tirade of embarrassing badinage that would nauseate a leper.”

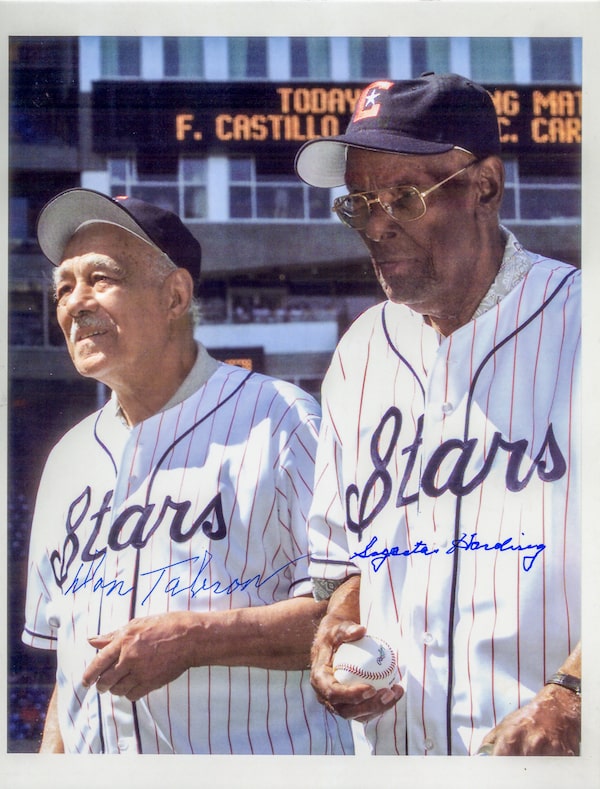

Sagasta Harding and Don Tabron, the two remaining players, represent the 1934 Chatham Coloured All-Stars at the Toronto Blue Jays’ event honouring the team in 2002.Courtesy of University of Windsor, Archives and Special Collections/Supplied

Ms. Jacobs admits that, like the white sports columnist, she had had the impression the All-Stars were perhaps a “too-rough team,” who sometimes overstepped “the limits of acceptable play.” Though she had chronicled some of the racist incidents the team faced – being denied food service and lodging in some out-of-town locations during their championship run – it was only after reading that fan’s letter that she recognized she had not fully appreciated what the team might have been dealing with both on and off the field.

A few weeks after the publication of that letter to the editor, the Daily News ran an unsigned piece about how the All-Stars, during a subsequent visit to Strathroy, having put up with “stinging insults, largely because of their racial characteristics,” turned the other cheek, faced the taunts with a smile and a laugh, and won over the crowd.

By the time the team captured the provincial championship, the players had also won the hearts of their fellow townsfolk. In the aftermath of the victory, doors seemed to open for the players and other Black residents. Boomer Harding worked as a postal carrier; his brother, Andy, who later played for the All-Stars, became Chatham’s first Black police officer. One player was invited the join the white Strathroy team as its captain.

None of the All-Stars wound up in pro ball: the major-league colour barrier didn’t fall until more than a decade later. But their success instilled a sense of pride and possibility in Black Chathamites.

A little over a week ago, Hall of Fame hurler Fergie Jenkins Jr. came back home to witness the unveiling of a bronze statue, which shows him in mid-throw. At the base of the statue is a plaque. It dedicates the honour to his mother, Delores, and his father, Ferguson Sr.