Construction of 30 Hudson Yards, seen in March of 2016.

Sam Hodgson/The New York Times

On the west side of Manhattan, south of Hell's Kitchen, you can still watch the trains roll into the old railyard that sits on the once-grimy, industrial Hudson River waterfront. But not for long.

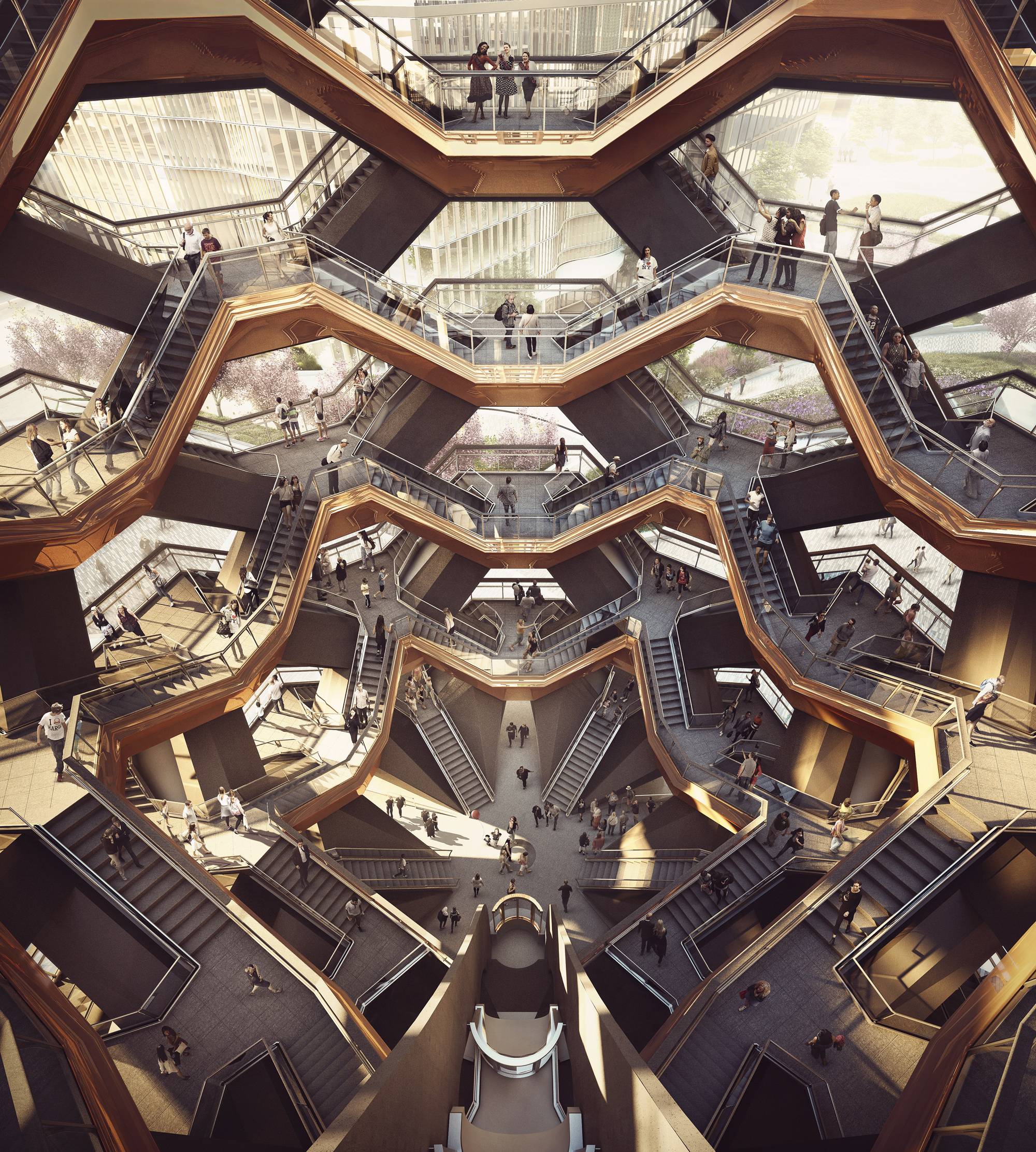

The clang of metal reverberates off concrete as cranes swivel through an overcast late-September sky, lifting and lowering pieces of what will soon be office towers. Welcome to Hudson Yards – the latest transformation of the New York City skyline and one of the most ambitious development projects in the world.

Two concrete platforms are being built over top of the working railyards, supported by stilt-like pillars sunk deep into the bedrock between the rail lines. Gardens, condos and office buildings are set to rise above. One 52-floor tower has already been built on the first platform. Construction on the second platform is expected to begin in the next 18 months. Over the next decade, several more skyscrapers and the city's first Neiman Marcus department store are set to be built around it, blanketing 28 acres.

Billed as the "New Heart of New York," the emerging hub is a testament to the engineering ingenuity needed to build in Manhattan, as the borough's supply of development-friendly land dwindles. It's also a symbol of the intensifying global brawl for commercial real estate in the United States – a battle Canada has dominated for the better part of a decade.

Hudson Yards is being co-developed by Oxford Properties Group Inc., the real estate arm of the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS), and U.S. partner Related Companies LP. On the very next block, Brookfield Property Partners LP has joined in with six more buildings under development, collectively called Manhattan West. They exemplify a trend that has seen Canadian pension funds, insurance companies and investment firms participate in U.S. commercial real estate deals worth $92-billion (U.S.) since 2007 – more than any other country – according to data firm Real Capital Analytics.

But that lead is slipping.

Canadians are fighting a fast-rising tide of foreign capital that is sending property prices even higher. Institutional investors from Asia, the Middle East and Europe – some scarcely registering as investors just a few years ago – are looking to the United States for noteworthy properties to stock their portfolios, and they are often willing to accept lower returns for access to the stable market, adding to pressure on the Canadian buyers.

"The allure of global capital to New York has always been high. It's always been one of the most – if not the most – liquid cities in the world for capital wanting to enter the marketplace," said Andrew Trickett, senior managing director at Oxford and a Canadian who has made New York home for the past seven years. "I would say today that is at an extreme high."

After a few years of building a presence in North America, China is on track to overtake Canada as the largest foreign buyer of U.S. commercial real estate this year. Investors say it's still early days for Chinese investment, and that the trend is poised to continue as the Asian giant's growing insurers and asset managers turn more often to alternative assets such as real estate – some for the first time. With this influx of global money, building prices have soared. Commercial real estate values in the United States have jumped by more than 20 per cent since their precrisis highs, according to a national all-property composite index developed by Moody's Investors Service Inc. and industry data provider Real Capital Analytics.

That's been driven by big deals, such as the 2015 sale of Three Bryant Park by Blackstone Group LP to Ivanhoé Cambridge Inc., the real estate arm of the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, and partner Callahan Capital Properties. The emerald-glass office tower perched on the edge of a landmark green space was sold in a speedy auction for a whopping $2.2-billion – one of the highest prices ever paid for an office tower in the city.

Three Bryant Park.

C. Taylor Crothers/Handout/Ivanhoé Cambridge

At the time, some local investors raised their eyebrows at the price. But a few months ago, Ivanhoé Cambridge proved to skeptics its valuation was justified, flipping a 49-per-cent stake in the building for nearly $1.2-billion, according to sources familiar with the sale. The buyer? An investment group related to the Hong Kong Monetary Authority.

As the hypercompetitive market intensifies, Canadians are being forced to reinvent their approach to U.S. commercial real estate. After funnelling money south of the border in the years following the Great Recession, some investors say it's time to slow down on purchasing new property and are selling off buildings to buyers willing to pay handsomely.

After testing the limits of one of the world's most recognizable skylines, the future appears relatively down to earth. Far-flung seniors' communities, sprawling industrial warehouses, student-housing complexes and unloved old buildings have taken on a new sheen.

"There's money from around the globe looking to invest in New York and in Boston, and in San Francisco, and in Seattle. There's tremendous capital demand for investments in these areas," said Doug Poutasse, head of strategy and research at Bentall Kennedy, the commercial real estate arm of Sun Life Financial Inc. "That is a real challenge."

The battle for Manhattan

Just as New York's financial sector was collapsing in the Great Recession, an investment window was opening in commercial property.

Canadian pension plans and other large investors, having emerged from the crisis relatively unscathed compared to their global counterparts, were looking to get in on the ground floor of the eventual U.S. economic recovery. Property prices had tumbled through 2008 and 2009 as investors came face to face with central bankers' plans to revive the global economy with low interest rates. In time, these low rates made alternative assets such as private equity, infrastructure and real estate more appealing.

In 2010, office, retail and apartment property values began to rise. For Canadian investors, it was a green light: They participated in more than $4-billion worth of commercial property deals in the United States that year – up from $880-million the year before, Real Capital's data show.

Toronto-based Brookfield Asset Management Inc., which has been among the most deal-hungry Canadian investors, made a $2.5-billion investment in U.S. shopping mall owner General Growth Properties Inc. Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, which had only been investing in real estate for a few years, bought stakes in two prime Manhattan office buildings – 1221 Avenue of the Americas and 600 Lexington Ave. – for $700-million. Today, CPPIB has well over one-third of its $40.8-billion (Canadian) real estate portfolio in the United States, up from 5 per cent a decade ago.

Also in 2010, Ivanhoé Cambridge set about selling properties and retooling its portfolio. Then it flipped into acquisition mode.

"Our timing was very good in the U.S. in that over the last four, five, six years in particular, we've seen a real resurgence in the office market generally in the U.S.," said Arthur Lloyd, executive vice-president of North American office properties at Ivanhoé Cambridge. Rents have steadily increased in many U.S. markets since the recession, and demand for work and living space has increased alongside the recovery. "Now we're at a point where prices have run quite a ways."

Deals done by Canadians have steadily ramped up since 2010, reaching a $20.8-billion (U.S.) fever pitch last year, according to industry data provider Real Capital Analytics.

Ask investors what's driving those recent price increases and there's a good chance they'll begin their answer with one word: Anbang.

Beijing-based Anbang Insurance Group Co., backed by other Chinese conglomerates, has arrived on the U.S. real estate scene in a big way. And seemingly overnight. Earlier this year, the company made a widely reported, but as yet unannounced, $6.5-billion deal for Strategic Hotels & Resorts Inc. from the Blackstone Group. That came on the heels of its $1.95-billion acquisition in 2015 of the Waldorf Astoria New York, which it is now preparing to turn into condominiums.

The Strategic Hotels purchase, if it is completed, will be enough to vault China past perennial leader Canada on the investment charts this year. Canadian investors have participated in $9.7-billion worth of property deals so far this year, according to Real Capital's data. Add the Anbang deal to the $7.9-billion in cross-border deals and joint ventures the Chinese have done, and the country would pull far ahead in the rankings.

And that's becoming the new normal. "Notionally, I think you're going to find that China will start to outstrip us – I mean, just the sheer volume," said Ted Willcocks, global head of asset management at Manulife Real Estate, an arm of Manulife Financial Corp. But where the money's coming from can be difficult to track. "We don't have all the transparency on some of the plans and some of the insurers that are coming out of China."

The rise of Chinese investment is one of the clearest examples of the inflow of capital that has come in search of direct investments in U.S. commercial real estate amid negative interest rates and threats of currency devaluation. As gross domestic product growth in China has slowed and stock markets have churned, local investors have sought places to invest abroad. At the same time, sovereign wealth funds in countries such as Norway are also growing and hunting for stable real estate investments, leading to more activity – and slimmer returns – in large U.S. cities.

While the market could turn at any moment – funds in the Middle East slowed spending amid the oil price collapse, for example – the U.S. government has also moved to encourage investment. Late last year, the U.S. Congress exempted foreign pension funds from the Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act (FIRPTA), potentially courting billions in new investments.

"Both China and Germany have come in really aggressively this year. And that's something we're keeping our eye on," said Mr. Poutasse of Bentall Kennedy, adding that it's difficult to predict how much capital could come from China in the future.

Oxford's Mr. Trickett said his interactions with international funds are pretty regular, given that Hudson Yards has been courting fellow equity investors for its many properties over the past several years, with many more projects to go. Japan's largest real estate company, Mitsui Fudosan America Inc., invested in 55 Hudson Yards; Australia's KAA Capital Pty Ltd. is backing 35 Hudson Yards; and China Life Insurance (Group) Co. recapitalized one of the residential towers.

What large funds are looking for is predictable. They "generally like to make sizable investments," Mr. Trickett said. New York appeals because "it's liquid, meaning there's always stuff available for sale here, no matter how good or bad the market seems to be. They're looking usually for office [buildings] to start because they're big transactions. And the buildings are big."

At the same time, tenants are becoming more discerning about their office space. Some investors say it's taking longer to do leasing transactions and landlords are starting to provide more concessions – from doling out capital to customize spaces to offering free rent at the front end of a deal.

Mr. Trickett said Oxford is having a "more difficult time today figuring out where real good opportunity is" than it did one year ago.

Down to earth

Canadian investors fed up with blockbuster office building auctions are turning to less-prestigious corners of the U.S. real estate market.

In search of higher returns – and portfolio diversity – some are eyeing industrial properties, smaller cities, and buildings that need redevelopment. For CPPIB, student-housing complexes and seniors' residences have been the ticket.

"We believe that the U.S. real estate market has recovered pretty fully from the global financial crisis, and so some of the segments of the market are pretty fully supplied with equity capital – and debt capital too, for that matter," said Hilary Spann, CPPIB's managing director of U.S. real estate investments, who is based in New York. "When we've made new investments, recently we've focused on segments of the market that are showing secular strength."

That means tracking demographic trends that could boost returns years in the future. If more aging baby boomers downsize and move into communities with various amenities, seniors' care and living facilities would benefit. Student housing is also poised to get a lift from increased enrolment in colleges across the United States.

"And those are both sectors that have a little bit less capital chasing investments at the moment – so there's a little bit less pressure on pricing there," Ms. Spann said.

Brookfield's notable real estate deals this year have also been outside the office sector. It bought Orlando-based Simply Self Storage in early 2016, noting that the market for storage space is fragmented. Brookfield, which like many funds has an international mandate, also bought a portfolio of student housing in the U.K. this year.

Still, this approach isn't for everyone.

"You wouldn't find us investing if somebody had a self-storage mandate across the United States, or in seniors' living," Manulife's Mr. Willcocks said. "It wouldn't be for us. We would stick to the main food groups."

That's in part because the returns used to pay insurance claims needs to be steady. But of the $20-billion (Canadian) that Manulife has under management, about $5-billion has been amassed over the past five years to be managed on behalf of other institutional investors. Manulife hopes to expand that side of the business, primarily in the United States.

Mr. Poutasse said Bentall Kennedy wants to invest in the cities where people want to work – a strategy the firm calls following the talent. But Bentall Kennedy has to see something that it can add to the building to boost returns, especially in New York. It recently was part of a deal for a building near the World Trade Center, which has among the most expensive leasing rates in Manhattan.

"We bought a building that had been actually bought by somebody else to be converted to residential space. They failed to get some of the office tenants out, so we're renovating it back to being an office building," Mr. Poutasse said.

At the same time, Canadians have been quietly selling off holdings.

Mr. Willcocks said a slow start to 2016 caused many investors to sit back and reflect on the "tremendous run." Manulife has transferred, seeded or sold about $1-billion of U.S. real estate assets this year – a larger turnover than normal in the portfolio. Fewer bidders are coming to the table, too, Mr. Willcocks said.

Mr. Lloyd is taking a similar approach at Ivanhoé Cambridge. "I've got a little more selling to do. I've got about another $1-billion (U.S.) before I can take a Christmas holiday," he said.

But don't count out the Canadians. For Oxford Properties at Hudson Yards, the course is set. Construction of the second platform will pave the way for more condo towers and offices to be built until 2025. Even then, Oxford and Related have bought a few nearby sites, betting their neighbourhood will be a hit.

"Our view is, if you're thoughtful, and you really look, you'll find unique opportunities. It may not be as easy with the competitiveness of capital," Mr. Trickett said. "Execution may be a little bit more difficult."

The ambition at Hudson Yards hasn't gone unnoticed. "There's no more complicated real estate project in the world today," Mr. Willcocks said. "I'm proud of our Canadian friends who are involved in it."