When a collective of artisans led by L.A.-based illustrator Tuesday Bassen accused clothing giant Zara of copying their designs in July, the world took note.

Dozens of pin designs by more than 20 artists – as documented on New York artist Adam J. Kurtz's site ShopArtTheft.com – had been "reproduced as pin and patch sets, embroidered decals and print-on apparel," according to the site.

It was reported as a serious transgression of intellectual-property rights, but for many of the artists in the thriving, mainly online, market for such items, it was simply one more to throw on top of the growing pile of copyright-infringement grievances.

"The thing with Zara in the summer – that's not a one-off thing," says Britt Saunders, designer and owner of Toronto's Sparkle Collective.

As far as Ms. Saunders knows, her work was not copied by Zara. However, the first design she marketed through her company – a baby unicorn enamel pin – has been duplicated by vendors from as far away as China and South America selling through major online marketplaces for as little as $2, compared to her $12. "It's so cheap, it's almost insane," she says.

Five small Canadian brands contacted for this article – Toronto's Queenie's Cards, Crywolf and Sparkle Collective, Montreal's Stay Home Club and Vancouver's Explorer's Press – all reported having been copied by various offenders this year.

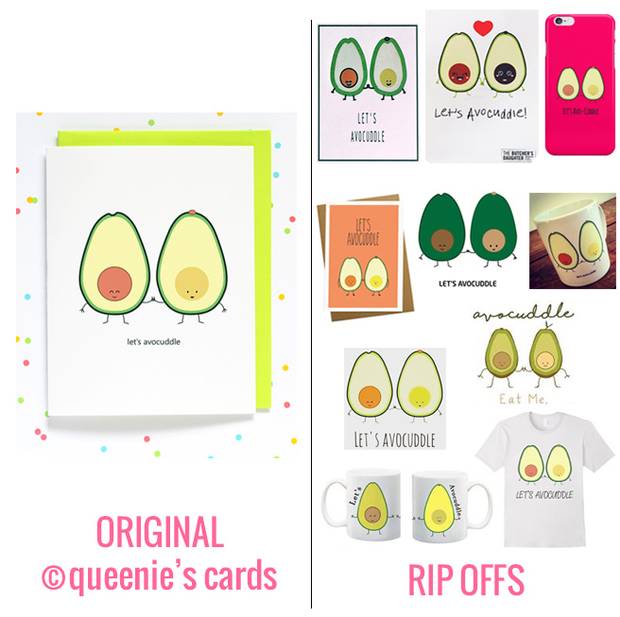

"It sucks. It's heart-wrenching to see somebody else copy your design," says Queenie's Cards owner Queenie Best, adding that the fake versions are usually of poor quality. Her "let's avocuddle" design – which depicts two halves of an avocado holding hands and is featured on a variety of her merchandise – has been copied regularly since its debut in 2014.

"It's just that feeling of someone taking something from you," says Crywolf co-owner Rose Chang, who says her designs, including a depiction of crying cloud, have been duplicated widely by many, including Zara. "It's kind of sad because you can't really do anything about it."

In Canada, copyright is automatically given on original work, and some artists take the extra step of registering their copyright at $50 per design. Trademarking a design, on the other hand, is complicated, time-consuming and significantly more expensive.

But because most of the duplicate designs come from beyond Canada's borders, a Canadian or even U.S. copyright is often not enough to protect against art theft. These small owner-operated businesses often do not have the time or money to go after copycats in court, and winning does not ensure damages would ever be paid. "I don't find there's often much of a point of pursuing it legally," Mr. Megannety says.

That makes Ms. Bassen's lawsuit against Zara somewhat unusual among craft-makers.

Olivia Mew, owner of Montreal's popular Stay Home Club, says she has been watching Ms. Bassen's case closely. Ms. Bassen initially spent $2,000 on lawyer fees to sue Zara, to little effect: a note she said she received from Zara in response saying her work lacked distinctiveness. Zara acknowledged the problem after media outlets began reporting on the allegations of copyright infringement. (Inditex, Zara's parent company, said in a statement to The Globe and Mail that it has suspended the designs in question from sale and is investigating the matter. When asked about other the incidents of copyright violation, the company said it has detected some cases and immediately acted to address them individually.)

"If we had to invest that kind of money to even begin to fight every case of this, we would never survive. The big companies know we can't afford it," Ms. Mew says.

It is easier to get third-party online vendors to drop an unauthorized copy.

And so artisans e-mail copyright-infringement complaints known as takedown notices, which request fakes be removed from the websites selling them – a mechanism supplied under the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). U.S. handmade crafts marketplace Etsy says it received more than 11,000 takedown notices last year from artisans claiming they had been ripped off, resulting in the removal of almost 186,000 product listings.

One silver lining is that the artists' fans are often more than willing to go to bat for them over copyright infringement. Mr. Megannety of Explorer's Press says fans routinely inundate offenders' social media accounts with what amounts to public shaming. The exposure as a consequence of that can help boost sales of the original products.

But being vigilant about duplications and issuing takedown notices can feel like an endless game of whack-a-mole.

Ms. Mew says her work has been duplicated by many, from small vendors to major chain stores operating in Europe, Brazil and Russia. When asked to comment, Ms. Mew sent a fresh screenshot from Amazon showing a series of t-shirts emblazoned with her company logo – a girl with four cats – being sold by third-party vendors for $20 (U.S.) less than her own price. However, the application of DMCA's Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act limits liability for copyright infringement for e-commerce sites provided they give rights-holders a method of issuing takedown notices.

Amazon said in a statement that it respects makers' intellectual property (IP) rights and demands its third-party sellers do, as well. "We encourage anyone who has an IP rights concern to notify us, and we will investigate it thoroughly and take any appropriate actions."

Ms. Mew said she has notified Amazon in the past of such concerns via its reporting mechanism, the takedown notice.

"There's a process for the Amazon-type copies that we try to find time to go through whenever we can," Ms. Mew says. "It involves alerting them to the infringement with a series of links and statements. They usually take things down pretty quickly, but they pop back up pretty quickly, too."

Without the time or resources to fight for their copyright, many are resigned to that fact that they cannot do much about being copied other than come up with the next big thing.

"That's what I keep telling myself," says Ms. Best of Queenie's Cards. "There will be another avocuddle."