Moroun started to build the on-ramps to his proposed new bridge—which would run alongside his Ambassador Bridge—long before he had a permit

Ryan Debolski

In June 2012, Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Michigan

Governor Rick Snyder strolled outside the elegant former headquarters of Hiram Walker on the Detroit River waterfront of Windsor, Ontario, beaming for photographers. They were there to publicly announce the long-awaited agreement to construct a new six-lane bridge to the U.S. auto-manufacturing capital. Harper didn't hesitate to put his reputation on the line. "This is the single most important piece of infrastructure our government will complete while I am prime minister," he declared.

Casting a shadow over the proceedings (metaphorically if not literally) was the almost century-old Ambassador Bridge that crosses the river a few miles to the west. The four-lane span is a lifeline of binational trade, carrying a quarter of all merchandise transported between Canada and the United States. Harper vowed that the new bridge, along with support facilities on both sides of the river, would reduce traffic congestion and create jobs. He also sent a warning whose meaning was perfectly clear to locals in both cities: "Make no mistake—whatever battles lie ahead, this bridge is going to get done."

Harper's target was a tenacious nonagenarian Detroit trucking billionaire named Manuel "Matty" Moroun. In 1979, Moroun bought the Ambassador Bridge, making it the only major span between the two countries that's in private hands. He's been ferociously defending his monopoly against assaults from governments, local residents and the media ever since, even spending a night in jail for contempt of court. His actions led Forbes magazine to brand him "the troll under the bridge."

Throughout the decades-long conflict, Ottawa has been Moroun's most formidable opponent. When the Canadian government began floating proposals for a rival bridge in the 2000s, Moroun countered with a plan to build a new crossing of his own—a six-lane replacement for the Ambassador Bridge right next to the original. Ottawa, backed by regional governments on both sides of the border, has long appeared to have the upper hand. But in early September, there was a dramatic reversal when the Trudeau government granted Moroun a permit to build his bridge. Meanwhile, the government-backed project—facing repeated delays and cost-estimate hikes—looks iffier by the day. With traffic volume down significantly since the saga began, some wonder if the whole idea shouldn't be scrapped.

Moroun, who at 90 still puts in six days a week at the office, avoids journalists—he's been burned too many times—leaving nosy questions to his top lieutenant, Dan Stamper. The 67-year-old president of the Detroit International Bridge Co. (DIBC), who has been by Moroun's side for 30 years, can't hide his satisfaction at the latest turn of events. "We finally see some light at the end of the tunnel," he says with a smile, seated in his office at the company's headquarters in a former school just outside Detroit. As Stamper gripes about government interference in private enterprise, Moroun himself suddenly appears at the door. Stooped but sprightly and wearing a dark dress shirt and high-waisted pleated blue pants, all he does is say hello and shake hands, then asks Stamper to come see him.

Matty Moroun, a 90-year-old trucking magnate has battled Ottawa for decades

CARLOS OSORIO/AP

When Stamper returns from his conference with the boss, he picks up where he left off. The government-proposed bridge "is just a way to take away our franchise," he says, shaking his head. He adds, "There's just something fundamentally wrong."

On that last point, residents, businesses and taxpayers would probably agree.

Mike Cardinal, whose family owns a retirement home near the Ambassador Bridge, has seen his Windsor neighbourhood of Olde Sandwich Towne damaged and demoralized by the unending bridge drama. Moroun bought up more than 100 houses here, but after the city denied him demolition permits, many have been boarded up and left to rot. "This was a slum imposed by a billionaire," says Cardinal.

Like many Sandwich residents and business owners, Cardinal was appalled when the federal government granted Moroun the go-ahead, but not surprised. "Trudeau made a deal with the devil," he says. "While the bureaucrats play checkers, Matty plays chess."

Moroun has been a controversial figure for much of his career. As a youth, he pumped gas at his father's two filling stations in Detroit. His dad later bought a small bus company, and after Moroun graduated from university, father and son expanded into trucking. The son assumed full control in the 1970s and built what is now called CenTra Inc. into one of the largest trucking and logistics providers on the continent, with 10,000 trucks on the road each day in the United States, Mexico and Canada.

As a regular toll-paying customer of the Ambassador Bridge, Moroun became intrigued by its investment potential. In 1972, he began buying shares in DIBC, then a publicly traded company in which Warren Buffett once held a 25% stake. But Buffett was worried the Canadian government would assert ownership and in 1979 sold his shares to Moroun, who proceeded to take the company private.

From the start, Moroun insisted that DIBC owned not just the Ambassador Bridge but a government-sanctioned monopoly. The bridge had been built by private financiers in the 1920s, and Moroun's lawyers have argued that a congressional act authorizing its construction gave the company a "perpetual and exclusive right" to operate a bridge across the Detroit River.

Ottawa didn't see it that way. In the 1970s and 1980s, the federal government launched a series of legal actions trying to assert its right to appropriate the Canadian half of the bridge. But as negotiations for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) heated up, the federal government relented, dropping the lawsuits and, in 1992, settling for Moroun agreeing to make improvements to the bridge and the Canadian customs plaza.

As automotive trade between Ontario and Michigan boomed in NAFTA's wake, the Ambassador Bridge became an increasingly intolerable bottleneck. Traffic across the bridge was climbing by about 10% a year, with 33,000 cars and trucks traversing it each day by 1999. With no other nearby access to Highway 401, Ontario's main commercial artery, trucks had to grind through downtown Windsor and were often lined up for hours at the bridge. "In a business that relies on just-in-time inventory, this was a killer," says Alfie Morgan, a retired University of Windsor business professor and long-time follower of the skirmishes between Moroun and Ottawa.

When a 2004 study by Ottawa, Washington, D.C., Ontario and Michigan concluded that the bridge needed to be expanded or replaced, Moroun moved to ward off potential competition by filing a proposal to build a new bridge. But Ottawa had had enough of Moroun and began developing its own plans for a bridge with the three other governments, with the cost pegged at $2.1 billion (U.S.).

So began the war of two bridges, which Moroun fuelled with expensive legal, lobbying and PR offensives. When Rick Snyder was elected Michigan's governor in 2010 and promptly sent a proposal for the government-backed bridge to the state legislature, Moroun funded a $5-million (U.S.) TV campaign claiming that "special interests and contractors" had cooked up the plan. He also founded a political pressure group, The People Should Decide, which gathered 600,000 signatures on a petition for a state constitutional amendment requiring a referendum on any proposed bridge.

A view of the Ambassador Bridge from a U.S.-side neighbourhood

Ryan Debolski

Moroun's efforts succeeded in stalling the government plans. Meanwhile, he bought dozens of properties in Detroit along the route of the proposed bridge—in effect, hedging his bets, as the government would have to buy the properties from him to proceed with its project. To further signal his displeasure, he stopped work on a contract with the Michigan government improving ramps and highway access to the Ambassador Bridge. After DIBC ignored several court orders to complete the work, Moroun and Stamper were jailed for 30 hours—although they were allowed to order dinner from the swanky Detroit Athletic Club.

Perhaps Moroun's time in the slammer cooled some of his indignation. Since then, he has been less brazen, opting to lobby and plod ahead with court cases instead of waging incendiary PR battles. But neither Moroun nor his executives have relented in their outrage at the idea that governments would spend billions of dollars to set up a subsidized competitor right next door to a successful private company's franchise. As Moroun's wife, Nora, put it in a rare interview with the Detroit News in 2010, "They want to destroy our family business and [have] government take it over. My husband is battling two countries and two governments: Is this the end of the American dream?"

There is one man Moroun and Stamper blame for much of the ongoing vitriol: Stephen Harper. After the Conservative leader assumed office in 2007, the government tried to ignore Moroun and focus on developing its own bridge. In 2009, Ottawa and Ontario started building a $1.4-billion, 11-kilometre extension of Highway 401 to the Windsor side of the proposed span (the extension was completed in 2015). By then, the new bridge had received almost all of the approvals it needed from environmental and transportation agencies in Ottawa, Washington, Ontario and Michigan. Veteran U.S.-born Canadian diplomat Roy Norton was appointed consul general in Detroit and charged with the task of lobbying local and state politicians to favour Canada's bridge proposal and oppose Moroun's. The formation of the Windsor-Detroit Bridge Authority (WDBA) in 2012, governed by a binational board of directors, was another important step toward the project's realization.

In May 2015, Harper took what appeared to be a victory lap. Joined by Snyder and two of Gordie Howe's sons at another ceremony on Windsor's waterfront, the Prime Minister announced Ottawa would name the new bridge after the Detroit Red Wings hockey legend. "He symbolizes that relationship" between the two countries, Harper said, vowing that the long-delayed span would be ready by 2020.

Michigan Governor Rick Snyder and PM Stephen Harper announce an agreement to collaborate on building a new bridge

Mark Spowar/CP

What the politicians didn't advertise was the lack of political appetite in Michigan or Washington to deliver any actual funding for this ambitious project. As early as 2010, Ottawa offered to lend Michigan the entire $550 million (U.S.) needed to connect the American side of the Gordie Howe International Bridge to Interstate 75 and to pay the full freight for the construction of the customs plaza, estimated to run $250 million (U.S.). That essentially put Canada on the hook for the entire cost of the bridge. What's more, estimates of the full construction cost are now closer to $4 billion, largely due to the steep decline in the Canadian dollar's value from the near-par level at the time of the project's announcement.

Stamper, meanwhile, insists DIBC's new bridge can be completed by 2020 for less than $1 billion (U.S.). Which is why Moroun and Stamper found it galling that Harper remained so gung-ho. "It was Stephen Harper's pet project—everybody knows that," Stamper says, adding that the Canadian PM refused to even meet with DIBC executives.

The Canadian government's plan was to fund its bridge through a public–private partnership. A private-sector consortium will pay most of the cost of construction and then have a 30-year commission to operate the bridge, with toll revenue used to recoup building costs. Three groups have been selected as final bidders for the contract, all involving heavy hitters such as SNC-Lavalin and EllisDon. This past August, however, the WDBA told the finalists it was extending the final-bid deadline to May 2018, to give bidders more time to develop their proposals for the increasingly complex project. That puts the earliest likely date of completion at 2023—three years past what Moroun has promised.

The biggest worry, however, is that economic shifts make it highly unlikely the new bridge will pay for itself through tolls. In fact, many experts argue there's no longer enough cross-border traffic to support two bridges. The number of cars and trucks travelling over the Ambassador Bridge per day has dropped by almost half from its 1999 peak, to about 18,000 now—below the levels in the early 1970s. Traffic at all border crossings between Ontario and the United States is down since 2000 by an average of 36%, says Ron Rienas, president of the Public Border Operators Association.

Much of the slide in car traffic is due to enhanced passport and security requirements after 9/11. But it is the decline in truck traffic that's of major concern to Windsor–Detroit bridge operators, since most cars travel between the two cities via the nearby tunnel. That drop is due to auto manufacturing draining away from Ontario and Michigan to Mexico in recent years. A quarter of all U.S. vehicle and part imports in 2016 came from Mexico, double the proportion in 1996. Over the same period, the percentage that entered from Canada declined from 39% to just 21%. Laurie Trautman, director of the Border Policy Research Institute at Western Washington University, expects the declines to continue and finds it hard to see an economic case for the Gordie Howe bridge today. "I don't think it's the best use of a massive amount of funds," she says.

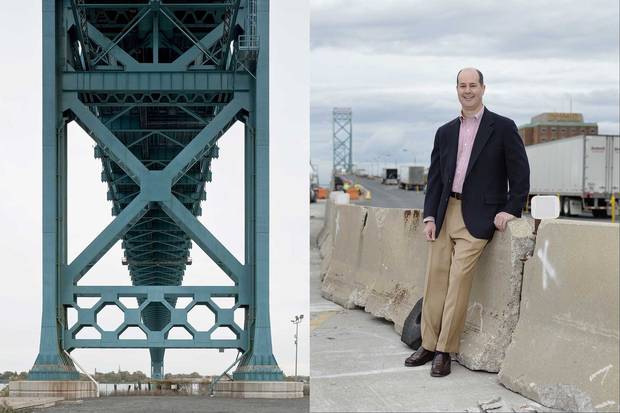

(Left) Under the Detroit side of the Ambassador Bridge. (Right) Matthew Moroun, Matty’s heir apparent, thanked Prime Minister Trudeau after the Canadian government granted a permit for the new bridge

Ryan Debolski

Stamper won't divulge the revenue the Ambassador Bridge generates, but various media estimates have pegged it at about $60 million (U.S.) a year. The lion's share comes from tolls (trucks pay between $4.50 and $6.75 per axle), says Stamper, plus proceeds from a big duty-free gas station on the Detroit side. Even if the Gordie Howe bridge managed to draw away half of the Ambassador Bridge's business, Rienas says "there isn't a snowball's chance in hell" that tolls will cover its operating cost and the $4-billion construction bill within 30 years. Even a highly optimistic 2010 study of the Detroit River International Crossing (as the proposed Gordie Howe bridge was then called), which forecast that cross-border traffic would climb strongly and the bridge would be completed in 2016, projected that tolls would fall far short of repaying building costs. "It is impossible to finance this project without a massive taxpayer subsidy," Rienas concludes.

Despite the warnings that there isn't nearly enough traffic to support two bridges, in September the Trudeau government granted Moroun a permit to build his new span. The move stunned local residents and commentators. "This is kiss-the-dirt humiliation imposed by a government that couldn't care less about the Windsor area," wrote Windsor Star columnist Gord Henderson. The following month, Transport Minister Marc Garneau insisted the government remains "100%" committed to the Gordie Howe bridge. Asked how Ottawa can justify the parallel projects, Transport Canada spokesman John Cottreau cites statistics on the corridor's vital importance to trade flows. "Having the Gordie Howe International Bridge and a fully functioning Ambassador Bridge will enhance capacity and reliability at Canada's busiest commercial crossing."

Alfie Morgan doesn't buy it. He and many other long-time local observers believe allowing Moroun to build a new bridge—at no cost to Canadian taxpayers—will make it easier for Trudeau to abandon the troubled infrastructure project his predecessor stuck him with. "As a politician once told me, you give a left signal and turn right," says Morgan. "There are hundreds of excuses for why it will not be [built]." Without guarantees of operating subsidies, contractors on the Gordie Howe bridge would find it difficult to line up construction financing and the project will die, Morgan argues. And if it does, Windsor will miss out on the jobs and economic activity a new bridge's construction would generate, as Moroun will likely use mostly American contractors.

Garneau and his officials stress that Moroun still has to meet strict conditions before he can build his bridge. Among them: Ottawa wants him to tear down the old Ambassador Bridge after he builds the new one. Stamper hopes to renovate it instead and keep it open, as a backup. And Michigan's State Historic Preservation Office has designated it as a historic site. Stamper believes some compromise will be found.

DIBC's quiet lobbying of the Liberals has clearly produced better results than open conflict with Harper's government. The day the permit was issued, Moroun's 43-year-old son, Matthew, who is a DIBC executive and almost as publicly tight-lipped as his father, issued a long statement that noted, "We especially thank Prime Minister Justin Trudeau."

Stamper is more reserved: "We're glad things have calmed down." He insists the new Ambassador Bridge will be built by 2020. Then it will be time for Matty Moroun's victory lap—surely well-deserved after four decades of battling with multiple governments. Moroun still gets up each morning at his lakefront mansion in the wealthy Detroit suburb of Grosse Pointe and walks on a treadmill for 30 to 45 minutes. He then commutes to his headquarters and puts in eight to 10 hours on weekdays, plus a half day on Saturdays. How much do you want to bet he'll be at the ribbon cutting?