Late last year, an elegant envelope, complete with a wax seal, arrived at the headquarters of Canopy Growth Corp., enclosing an invitation for chairman and CEO Bruce Linton to attend a corporate brand summit in Banff, Alberta. The event was the fourth instalment of The Gathering, which bills itself as "an informal coming together of the enlightened, influential illuminati" behind the world's best brands.

Linton had never heard of it, but on February 21 he duly presented himself at a private dinner attended by VIPs from the likes of Visa and Airbnb. Starting to realize this summit was a big deal, he watched with growing excitement as close to 800 people poured into the Fairmont Banff Springs Hotel over three days to hear 30 speakers—including him—expound on the finer points of consumer marketing. At the concluding gala, Linton collected the award for Emerging Cult Brand of the Year, one of 11 honorees that included Levi's, ChapStick and Zappos. "It was rocket fuel for the way this brand is gonna grow," he says.

If the man still sounds giddy more than a month after the event, it's because the brand in question doesn't get much respect. Tweed, Canopy's principal offering, is a line of medical marijuana, which is perfectly legal as long as you buy it with a doctor's prescription. But a lot of people confuse Linton's product with illegal weed sold in retail dispensaries for recreational use, making it exceedingly difficult for him to build credibility for his fast-growing company.

Today, Canopy is Canada's largest medical marijuana producer by far, controlling about half the nation's market. Since starting from scratch in 2013, Canopy has posted some spectacular numbers. Its share price tripled last year. In November, it shot past $1 billion in market capitalization to become Canada's first marijuana unicorn, then briefly cracked $2 billion a few days later. This past March, Canopy joined the S&P/TSX Composite Index, which means that large index funds will pick up its stock automatically. Through a series of acquisitions, the company has amassed six factories and a massive greenhouse in Ontario's Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Linton is racing to expand before marijuana becomes legal for recreational use—currently set for 2018—and the market truly explodes. Last November, Canaccord Genuity analysts Matt Bottomley and Neil Maruoka estimated there could be 3.8 million recreational marijuana users in Canada by 2021, and annual sales could hit $6 billion. In preparation, Canopy is pouring money into marketing, trying to create a distinctive brand for Tweed in a sea of undifferentiated buds. In its splashiest move to date, the company signed a promotional deal last year with pot-hoovering rap icon Snoop Dogg.

None of this, however, has impressed Bay Street's biggest investment dealers and money managers. If anything, the surge in Canopy's share price and that of other marijuana producers has cranked up fears of a pot-stock bubble. "Canadian banks have a hard time backing entrepreneurs of any ilk—especially something as novel as medical marijuana," says Neil Selfe, head of boutique investment firm Infor Financial Group and one of Canopy's few institutional supporters. Meanwhile, police efforts to contain a proliferation of dispensaries skirting the law have added further uncertainty to the future of marijuana as a business. Linton is going to need all the prizes he can get to gain the sheen of respectability he so desperately wants.

It's early March, and Linton is facing a day full of pitch meetings on Bay Street, but he's happy to drop by on short notice at The Globe and Mail to tell his story. He arrives early, wearing a dark three-piece suit and a white shirt but no tie, carrying a coffee and a banana. He has the rough-around-the-edges charm and exuberance of a stock promoter and, at 50, retains a slight rural twang that hints at his upbringing on a Southwestern Ontario farm.

Linton's "aha" moment came in 2012, when he read a newspaper article about medical marijuana. At the time, he was in what he calls "a quiet period with work" following a run of ventures in the Ottawa tech community. After graduating from Carleton University with a degree in public administration in 1992, he went to work for telecom magnate Terry Matthews at Newbridge Networks, where he rose to head up CrossKeys Systems, a company spun out of Newbridge.

A few years later, he struck out on his own with WebHancer, which developed customer-tracking software. WebHancer crashed in the millennial dot-com bust and Microsoft bought up the remnants, but Linton found the experience valuable. "It was the first time I did this 'build it, grow it, work it, push it' thing," he says.

He shook off the failure and joined Clearford Water Systems, a start-up launched by veteran Ottawa entrepreneur Rod Bryden that aimed to build municipal wastewater treatment systems in India, China and South America. Linton served as CEO from 2005 to 2012. "I flew 268,000 miles in one year," he recalls. Exhausted from the pace, he was intrigued when he read about police chiefs pleading with the Harper government for clearer rules around growing and selling medical marijuana. The Tories wanted to create "a supply chain for something that has never had an organized supply, for which there was a huge market, but with tons of questions," Linton recalls. Even better, pharmacy chains said they wanted nothing to do with marijuana, limiting the competitive field. It sounded like a big—and less gruelling—opportunity.

In March, 2013, Linton had coffee with another Ottawa tech entrepreneur, Chuck Rifici, who was thinking along similar lines. Rifici says the duo established Tweed Marijuana Inc. (renamed Canopy Growth in 2015) as "a true partnership," with Rifici as CEO responsible for operations, and Linton as chairman and chief money-raiser. "Bruce is very good at doing deals," says Rifici.

The following June, Tory Health Minister Leona Aglukkaq unveiled new rules that barred sick people who wanted to smoke marijuana to control pain, nausea and other symptoms from growing their own weed. They now had to buy the drug from licensed growers. But to receive a licence, growers had to have a production facility inspected by regulators. Still, as Linton had learned in the telecom business, regulatory barriers can be great as long as you get behind them. "You needed a lot of money to build your first facility," he says. "And that was going to make it much harder for 99% of the people who wanted to do this."

Finding a factory proved complicated because many Canadian municipalities bar businesses from growing and processing crops in the same building. But the company found what it needed in Smiths Falls, southwest of Ottawa. The Hershey Co. had shut down its Canadian chocolate factory there in 2009, after 45 years. With almost half a million square feet spread over eight buildings, the plant gave Canopy plenty of room for future expansion, and local officials were happy to welcome the new business.

To buy the factory, Canopy needed $1.6 million, plus 10 times that much to start up production. Trying to raise money from friends and family brought a predictable reaction. "I asked my brother and some guys I had worked with in other businesses, and they're, like, 'Are you out of your mind?'" Linton says. He and Rifici managed to scrape together about $3 million from Ottawa-area investors. For the rest, Linton headed down to Bay Street looking for help from an investment banker. He didn't even bother approaching the bank-owned dealers, which are leery of start-ups and anything controversial. "Right away, you're off to Canaccord or GMP," says Linton—the second-tier independents more willing to take risks.

Neil Selfe, then a managing director at GMP, had crossed paths with Linton often in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when Selfe was head of technology, media and telecom investment banking at RBC Capital Markets. He believed Linton had the entrepreneurial mettle and vision, but to pitch a start-up to early investors, "the business plan had to make sense too," Selfe says. It was a risky venture, Selfe concluded, "but we thought we had a good shot at making people money."

It was tough going at first. Linton was raising small amounts in private placements for a few cents a share. One or two individuals would invest at a time, and "you had to chase 100 people to get them," he says. The company almost went bankrupt three times in late 2013 and early 2014.

Then, suddenly, Linton's luck turned dramatically. As commodity prices started to collapse, speculative investors who normally take flyers on junior mining companies began looking at medical marijuana. By the spring of 2014, says Linton, "I had to beat them away with a stick."

In April, the company took over a dormant shell company on the TSX Venture Exchange and became the first publicly traded marijuana outfit in Canada. More importantly, going public meant the company could do bought deals, in which a dealer or a consortium buys an entire new share issue, then sells the shares to money managers and individuals.

Soon after Canopy went public, however, the two co-founders had a boardroom showdown. In August, the board fired Rifici. Rifici sued for wrongful dismissal, and the suit is still outstanding, but he's philosophical about his experience. "I'm certainly not the first founder to be removed from a start-up," he says.

Since then, with Linton in charge of operations as well as financing, the company has raised more than $150 million from seven share issues. Despite Canopy's growing size and market clout, the big banks and their dealers remain glaringly absent. They haven't raised money for Canopy, their mutual fund managers haven't invested in its stock, and their analysts don't cover the company.

If anything, the bias against marijuana plays at the Big Six is hardening. In 2015, Royal Bank of Canada cut off Canopy's corporate account. Last September, Scotiabank and Royal Bank stated that they would no longer serve marijuana-related companies.

Linton insists that he's getting lots of institutional interest on trips to New York and Boston, partly because so many fund managers are fans of Snoop. "He is an iconic individual in America," Linton says, "and doesn't seem to attach himself to a single demographic." Perhaps, but it's hard to see a dope-smoking rapper changing many minds on straitlaced Bay Street.

Courtesy Tweed

Canopy's headquarters and main factory in Smiths Falls embody some wacky contradictions. The town's police station is across the street. The factory's lobby has a big Tweed logo at the back, yet there is also an old brown Hershey's chocolate sign.

Close to 250 people work at this facility, about half in production, and the rest serving customers online and by telephone and in administration. The office is a typical cubicle farm—except for several colour photos on the walls of Snoop in a Tweed T-shirt giving a two-thumbs-up, couch cushions emblazoned with the word "Hi," and a "Munchie Bar" stocked with chips in one corner.

Then there's the weed smell. It's pungent in the lobby, and overpowering in the production facility. The factory floor looks like a brightly lit lab scene from The X-Files, with employees in hairnets, gloves and surgical masks. The company initially grew its product from seeds, but soon switched to taking clones from mother plants—housed in two "mom rooms" behind glass—to ensure consistency. "It's like a nursery, and they're the babies," says Jordan Sinclair, Canopy's director of communications, of the cloned plants.

The Mom Room at Tweed

After about a month, the offspring are moved to one of Canopy's 18 flowering rooms, where they take between nine and 12 weeks to mature. Following curing, the buds are harvested and trimmed, then placed on large trays to dry. Several buds end up in individual plastic childproof jars, which are then boxed up and sent to customers by courier. Popular varieties include Kosher Kush, Boaty McBoatface, and Ocean View by Snoop.

Daily shipments from the plant have climbed roughly sixfold since 2014, reaching about 150,000 grams on the company's first million-dollar sales day in February. Yet the chances of sneaking out even a single bud are slim. There are security cameras everywhere, and Canopy keeps the footage for two years. Sinclair says Health Canada has inspected the plant nearly 100 times since 2014.

All told, Canopy has invested around $50 million in the Smiths Falls facility, yet is only using a third of the complex. It has five other factories, acquired by tapping its soaring stock to buy competitors (see "Wheeler Dealer"). The biggest deal to date has been Mettrum Health Corp., Canopy's largest Canadian rival, which it acquired in January.

While Canopy's production potential has risen dramatically, its revenues are still tiny. With the addition of Mettrum, the company has half of Canada's legal market—registered patients who have prescriptions from a physician—yet that represents only about 50,000 customers and sales of just $44 million last year.

The United States, where recreational marijuana is legal in eight states, is a tempting market for growth, but Linton isn't interested because it's illegal federally. "There will only be some legal states, each with hundreds of producers," says Linton, creating highly competitive regional markets. Instead, Canopy plans to look to Germany, Brazil and Holland for expansion, where recreational marijuana is legal—and where regulations don't create the muddled retail landscape he faces in Canada.

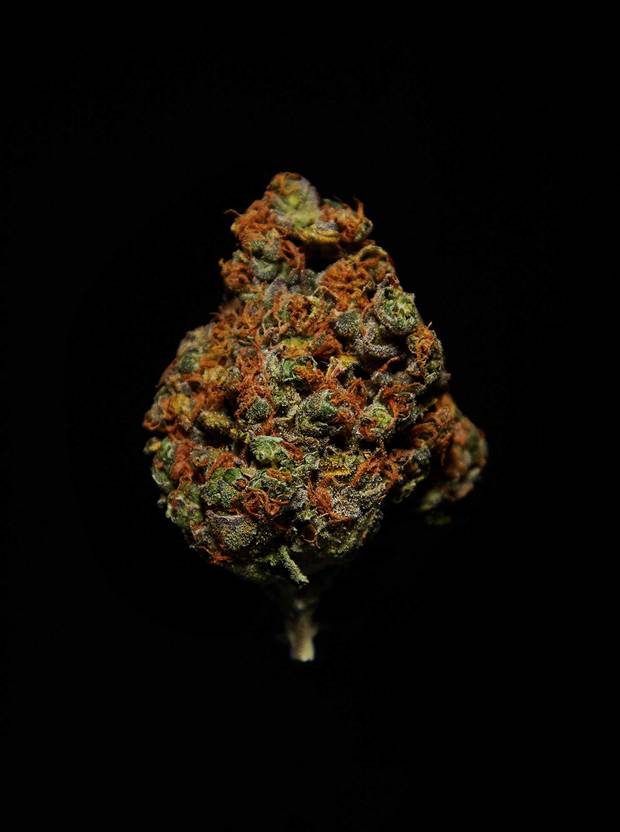

TDW Lot #2 (Proprietary strain) Indica. Appearance: impressive robust buds. Aroma: pungent and complex. Experience: heavy buzz, ticket to nap city

Rémi Thériault

It's Friday night at a Canna Clinic marijuana dispensary in midtown Toronto. Located above a sushi restaurant, the outlet is easily the busiest store in the neighbourhood. More than 100 people are jammed in and lined up at three counters. Behind one counter, half a dozen staffers—mostly 20-ish guys in hoodies—advise customers about the product. "This one turns down your brain, but it's not dissociative," one tells Daria (not her real name), an office administrator in her 40s. Then, showing her a plastic bucket full of buds of Comatose brand, he notes, "This will put you right to sleep."

Canna has seven outlets in Toronto and six in B.C. Like most other chains, it maintains a veneer of conformity to the rules. New customers are handed a clipboard with an application they must fill in. They also have to do a short Skype interview with a "health care professional"—a naturopath—and bring photo ID each time they come back. Daria buys three grams of Comatose, plus three apiece of Grape God and Rock Star, for $10 a gram. The staffer weighs each strain, puts it in a clear plastic bag, then scrawls the name on the side.

Stories like this drive Linton nuts. According to Health Canada, dispensaries like Canna do not meet legal requirements. However, they are not a high priority for law enforcement. Canopy doesn't distribute through dispensaries. It conforms to more than 1,000 pages of regulations. Its product is rigorously tested to ensure that it delivers the chemical content it claims. The company sponsors a national campaign against drugged driving by Mothers Against Drunk Driving and a clinical study of 6,000 patients to gauge the health effects of cannabis. It doesn't sell edibles, which might easily be consumed by kids by accident.

So Linton is angry he's competing against dispensaries that get their product from unidentified and almost certainly illegal sources. "If you're buying from a guy who hands you a Ziploc, you're buying from a bad guy," he says. (Two Canna Clinic managers refused to offer comment or identify the chain's owners.)

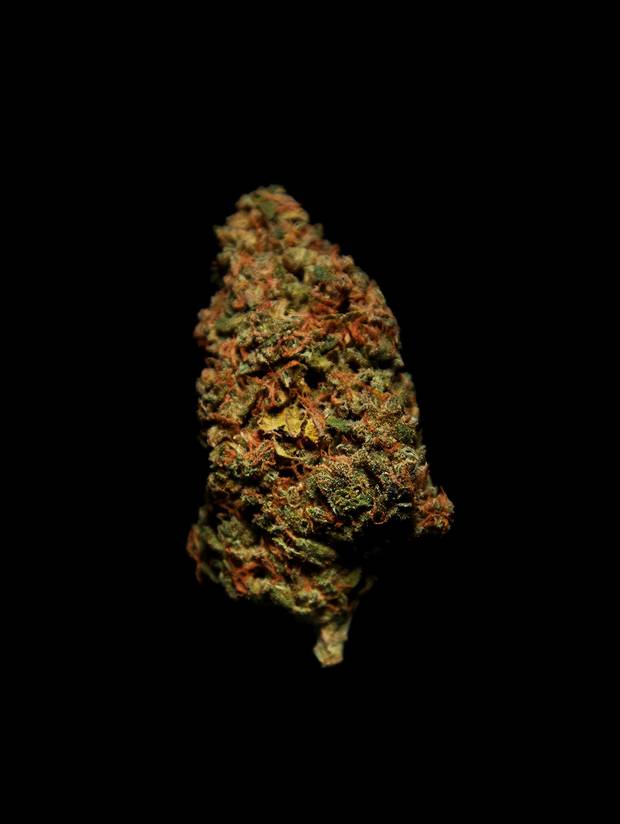

Super Lemon OG (DNA certified). Strain: indica-dominant hybrid. Appearance: rich green flowers, apricot hairs. Aroma: citrus fruit, lemony, sweet finish. Experience: balanced after-dinner buzz

Rémi Thériault

Bad or not, dispensaries like Canna have a significant edge over mail-order—starting with speed. Further back in line at Canna is Allison (not her real name), a Toronto pastry chef. After she grew worried about "the police bursting through the door" at dispensaries last fall, she went to her family doctor and explained that she was anxious, and having trouble sleeping. The doctor referred her to a specialist MD who runs a marijuana referral clinic. He interviewed her, performed a urine test for drugs, then gave her a prescription that allowed her to set up an online account with Canopy.

But two of the three strains Allison wanted had been sold out for months. (Tyler Burns, Canopy's head of investor relations, acknowledges there were "supply issues" in 2016.) A third, by Snoop, "wasn't that great," she says. There was also a five-gram minimum order per strain, plus taxes and a shipping fee. It's much more convenient to shop at dispensaries, she says. She's never had quality problems, and "the people there are cool and they give really good advice."

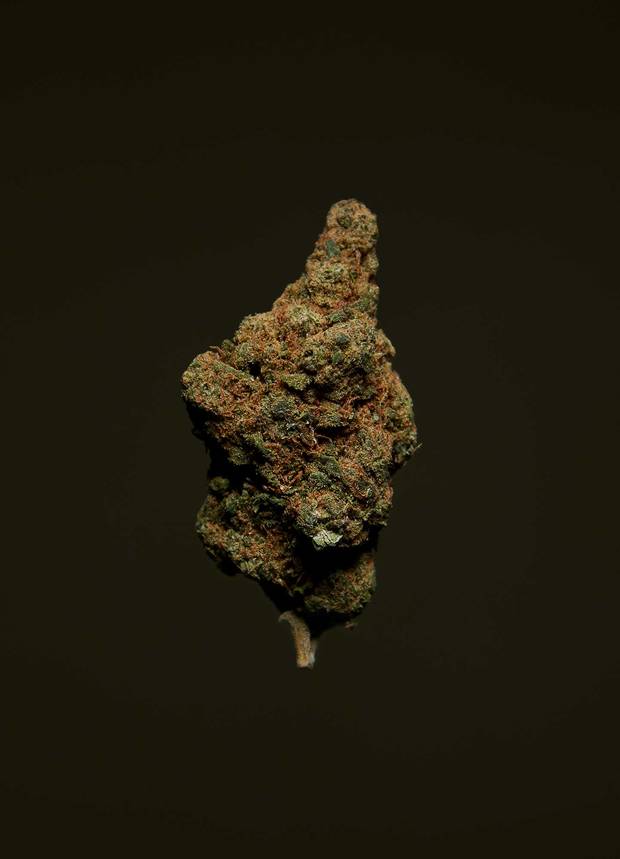

Bakerstreet (Hindu Kush). Strain: indica. Appearance: dense and covered in crystals Aroma: earthy, spicy notes with a dank finish. Experience: definitely baked and relaxed

Rémi Thériault

While Linton and the handful of analysts who cover the company see potential for significant sales once recreational marijuana becomes legal, for the moment Canopy's shares are staggeringly overpriced by just about any conventional financial ratio. In early April, they were trading at more than 200 times forecast earnings per share. The stock's volatility is also a major drawback. Within a single month late last year, Canopy's share price soared from $7 to $13.45, then dropped again to $8.25.

The lack of detail about the planned legalization hasn't helped the company win over institutional investors. After a federal official suggested that the Trudeau Liberals would let the provinces set the rules for the sale of recreational weed, Canaccord Genuity's Maruoka and Bottomley released a report stating "valuations are stretched" for the top medical marijuana producers.

"We all know when government gets involved, prices get controlled, supply gets controlled, profit gets controlled and the opportunity suddenly shrinks down," Michael Newton, a portfolio manager at Scotia Wealth Management, said in an interview on BNN last fall—before his employer told him he was "no longer allowed to discuss marijuana stocks." In fact, the few big institutions with significant holdings in Canopy are reluctant to talk. Neither Ted Whitehead, manager of Manulife's Growth Opportunities Fund, nor Mark Schmehl, manager of Fidelity's Special Situations Fund, returned phone calls.

Linton says Big Liquor, Big Tobacco and Big Pharma are all watching the evolving marijuana landscape with much interest. He wouldn't be surprised if pharmaceutical companies became big players in the market even before the governments have clarified the rules. He wants to stay at Canopy's helm at least until legalization of recreational use—the end of Prohibition.

While Linton insists he doesn't smoke his own product—"I have no medical prescription, nor require it"—the minute he can purchase his company's weed legally, he will be one of the first people in line, he says. "After five years in this sector and what it's taken to build it, I could use a very euphoric, tension-releasing hour or two."

Sunset (Leafs by Snoop). Strain: indica. Appearance: deep green and frosted buds. Aroma: sharp, spicy, clove-like notes. Experience: warm high, hello beloved couch

Rémi Thériault