Our plane has just landed on King Christian Island, part of Nunavut’s Sverdrup Islands archipelago, 415 kilometres northwest of Resolute Bay, but we are too busy and frenzied to take in the scenery.

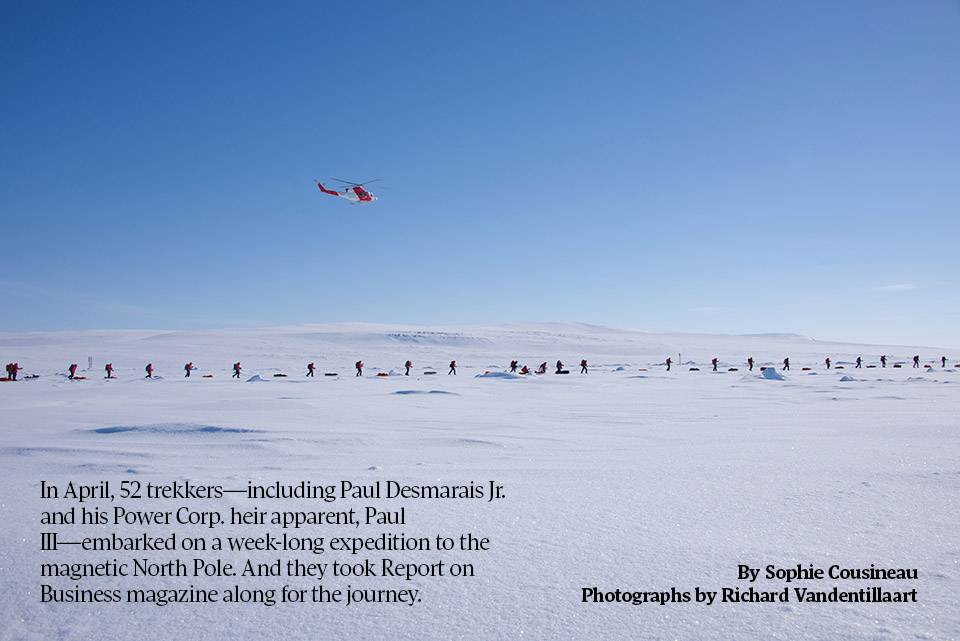

First, we unload the cross-country skis, backpacks and polar-expedition sleds from the Basler, the old, retrofitted DC-3 that flew us here from Resolute—Canada’s northernmost community, after the Nunavut hamlet of Grise Fiord. Then we clumsily set up our tents to shield ourselves from the Arctic wind. And then we wait for the last of the 52 trekkers in our party to be dropped off.

But just as the orange Basler—our last link to civilization—takes off into the immaculate blue sky, the sheer beauty and utter madness of our endeavour hits us like a snowball in the face. We are at the edge of the world, on an endless sea of snow and ice. There is nothing else in sight. And before anyone will fly us out of the ungodly cold that freezes everything it brushes within mere minutes, we will have to tough it out for an entire week.

What were we thinking? No one dares say it aloud—not Power Corp. chairman and co-CEO Paul Desmarais Jr. or former Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan head Jim Leech, not Transcontinental president and CEO François Olivier or veteran financier Tim Hodgson—but the question hangs over our heads like a speech bubble in a comic strip.

Twenty-two executives, 12 veterans, nine guides, two Olympic hockey players, a documentary film crew, one Czech German shepherd named Demon, and me, the lone reporter, have signed on to ski close to 100 kilometres to the magnetic North Pole—or where it stood in 1996, since its location moves constantly. Together, we form the largest Arctic expedition ever.

Led by Richard Weber, a veteran explorer who has lost count of exactly how many trips he’s made in the Arctic—somewhere around 60—the expedition aims to raise $1.75 million for True Patriot Love, a foundation that helps soldiers and their families deal with the physical and mental after-effects of their military assignments. The executives have paid $25,000 apiece to be here, and they would sooner die than fail to reach our destination—polar bears, exhaustion and bitter temperatures be damned.

For many, this journey comes at a pivotal moment. The Desmarais family, for instance, is laying the groundwork for the third generation to head Power Corp. Olivier is steering the country’s largest printer in a new direction to ensure its future. For Leech, who retired last year at 66, it’s an excuse to put off any decision about his post-Teachers’ future.

It also comes at a turning point for the soldiers, since Canada ended its 12-year mission in Afghanistan this past March. As the soldiers journey to the North, symbolically leaving their scarred past behind them, they will trek side by side with some of the leaders who will shape Canada in the 30 years to come.

In our puffy red Canada Goose parkas, our faces hidden behind balaclavas and snow goggles, it’s hard to tell one another apart. To figure out who’s standing next to you, you have to look down and read the name tag stuck on their skis.

Each trekker has his own reason for being in the Arctic on this April day. For Paul Desmarais III, the eldest of Paul Jr.’s four sons and a co-chair of the True Patriot Love expedition, it is soldiers like Sergeant Bjarne Nielsen.

In 2010, Nielsen was leading a patrol in Nakhonay, a village in Kandahar province, when an improvised explosive device sent him flying through the air. He lost his left leg and his left arm at the elbow. And as he lay in a hospital bed for 5 1/2 months, there was a time when he even lost the will to live. “I used to jump out of airplanes and kick down doors, and my body was all messed up,” says the 34-year-old sergeant from Petawawa, Ontario. “What was I to do now?”

Four years later, here he is, poised to take a journey that will mock the death he so narrowly escaped in Afghanistan. With him is the bandaged-up teddy bear given to him by his 10-year-old daughter Heather as he lay in hospital. “Everybody goes through hardship,” says Nielsen. “What matters is to persevere through adversity.”

The original plan was for B, as Nielsen is nicknamed, to ski to the pole. After injuring himself in training, however, B’s army doctor recommended he use a sit-ski cross-country sled. But when B tested it out in Resolute Bay, it kept tipping over. Prosthetist Patrick Lebel enlisted the help of two resourceful Resolute mechanics. On the evening prior to departure, they welded a horizontal bar onto the sled, then attached a pair of old snowmobile skis—and no more rollovers.

B will use poles to push himself forward, while his teammates (including the Desmarais boys) take turns pulling him—on top of carrying their own backpacks. When they’re on B duty, they’ll have to hand off their sleds full of gear, fuel and food to someone else, who must haul two.

Both Desmarais are willing to do whatever it takes to get B to the pole. When Paul III asked his father to join the expedition, the elder Desmarais said yes almost instantly.

“I am very sensitive to the plight of soldiers returning from Afghanistan,” says Paul Jr.

He was very close to his mother’s father, Ernest Maranger, a member of the famed Black Watch regiment who fought in the trenches of France during the First World War. “He taught me what it meant to be a soldier,” he says. Paul Jr. is also eager to dispel a myth about French Canadians. “There are still a lot of people in English Canada who talk about the conscription [crisis of 1917] and who believe, falsely, that French Canadians don’t back the army,” he says. “Many have died for the country during the two world wars. For me, it is important to send the signal that we also support the army.”

But this is also a chance for Paul Jr. to spend more time with his 32-year-old son, who has just arrived at Power Corp.’s Montreal head office after 13 years outside Quebec. “This is a nice start to a closer business relationship with my father,” adds Paul III, who left his position in risk management at Power Corp.’s Great-West Life in Toronto to become vice-president at the family-controlled holding company. There, he’s being groomed to take over the $30-billion-a-year conglomerate with his cousin Olivier, the son of Paul Jr.’s brother, André Desmarais. Paul III and his cousin, a lawyer by training born just seven days after him, will split the responsibilities the same way their co-CEO dads do: Paul III will look after Power’s European interests, while Olivier will tend to the company’s media assets and Asian investments.

They still have a few years to learn the ropes. Desmarais Jr., who turns 60 in July, says he has seven or eight years until retirement. And even then, he won’t leave business entirely. He’s too competitive for that, a fact he proves when he takes on his hefty son at the traditional Inuit wrestling game of arm-pulling during our stay in Resolute—and wins. (“It’s so embarrassing,” confesses Paul III, rolling his eyes.) Paul Jr. intends to work with his other sons, Alexandre, Charles-Édouard and Nicolas, who launched AppDirect, a cloud service marketplace based in San Francisco (it made Forbes’s list of most promising companies). “I want to help them build their own companies,” he says.

It’s midafternoon by the time we leave our camp on King Christian Island, and we’re already way behind schedule, because high winds held us up back at the Resolute Bay South Camp Inn for two days.

To kill time, most of the trekkers sat around their hotel rooms watching playoff hockey or reruns of Jaws, staying limber by doing yoga stretches on the floor.

But Eric Boyko—whose company, Stingray Digital, operator of the Galaxie music service, grew out of the Montreal-based tech incubator run by Paul Jr.’s wife, Hélène Desmarais—had brought along a deck of cards. Before long, he’d rounded up a group that included the Desmarais boys, François Olivier and M&A specialist Daniel Labrecque to play Asshole, a card game whose rules are a hazy memory from high school. The group spent hours on end playing in the hotel’s cafeteria, drinking herbal tea and artificial fruit punch from a fountain (Resolute is a dry community).

“This is the best day of my life,” Boyko bragged repeatedly on Day 1 of the Asshole marathon, with Desmarais père et fils haplessly stuck in the roles of vice-asshole and asshole. Paul Jr. had the hardest time containing his aggravation, but by the time I joined the game the next day, he’d reclaimed his CEO title, and his smile.

The overheated cafeteria is a distant memory as we ski into the cold in a jagged line. The trekkers have been divided into seven groups, with names like the Arctic Foxes, the Belugas and the Caribous. Each team is supposed to ski together (and sleep, cook and eat as a group, too), but some of the executives, impatient to leave, forge ahead on their own—a move that rankles the soldiers, who’ve been trained to stick with their comrades, no matter what.

This was meant to be a light day, to get us used to the energy-sapping cold, but since we need to make up time, Weber decides we’ll have to travel for five hours, with just two breaks. When we make our first stop, our shoulders are aching, and we’re all dying to throw off our backpacks. But no one wants to rest for long; the cold engulfs our bodies as soon as we stop. By the time the last trekkers make it to the break point, the first are already ready to leave.

Trekking in the North is an exercise in sweat and food management. Sweat, which freezes on the body, is the enemy. And so we are underdressed for the -20 C-plus cold to try and avoid it: one base layer, one fleece sweater and one shell coat. Moving non-stop is not enough, though. To stay warm, we must stuff ourselves with food at every break, taking in around 5,000 calories a day. The lunch menu contains enough fat to make your liver cry for help: frozen slices of fried bacon and cured beef, dense fruitcakes, saucisson, nuts, Zero bars and homemade chocolate truffles bigger than golf balls. For dinner, we can look forward to cheese and pâté on crackers, followed by double portions of freeze-dried meals.

It is not a diet everybody can stomach. For the life of me, I cannot eat the frozen lard and unashamedly spit it out. The same goes for Paul Jr., who had his gall bladder removed. Fearing a spasm attack that would floor him, he brought along his own protein pucks—dense cookies made of oats, chocolate and nuts. “My biggest fear is to slow down my team or to be evacuated for medical reasons,” he confides.

We finally stop for the day after 16 kilometres, our calves throbbing, in a place that looks no different than our starting point. Without a watch, I have no clue what time it is. By late April in Nunavut, the daylight never switches off.

Each team sets up their rounded nylon tents (commissioned by Weber specifically for this trip), with skis and poles as supports. Then we build igloo latrines using saws to carve out snow bricks. They offer a welcome bit of privacy for the nine women on the trip, who have no place to hide if nature calls on the barren frozen sea.

Once inside the tent, with the heat of the small gas burners set up at the centre, our bodies melt, losing all willingness to move. We just sit in a circle, staring numbly at the Christmas tree of mitts hanging with safety pins from the ceiling. Our team’s guide—Richard’s son, Nansen Weber—fills our thermoses and the pouches of our freeze-dried meals with boiling water. Replete with beef Stroganoff and sweet-and-sour pork, nothing short of a fire could persuade us to run outside.

And yet, before we can sleep, we must empty the tent entirely to set up our floor mats, mattresses and sleeping bags, which take up every bit of space, since the tents measure just three metres in diameter. Within seconds of unzipping the door, any warmth we’d built up disappears instantly.

The cold is not the only source of discomfort on that first night. There are only one or two women per group, and we must all change in front of our teammates. My group, the Caribous, includes CPPIB vice-president Jim Fasano and his stepfather, Scotiabank senior vice-president Andy Lennox. The rest of us—real estate investor Peter Aghar, soldiers Dan Lee and Dan Scott, and me—are complete strangers.

We squirm out of our sticky clothes with some attempt at modesty (which disappears completely by the end of the journey) and into our pyjamas, neck tubes and tuques, and glide quickly into our icy sleeping bags. Each of us is equipped with a pee funnel and bottle we pray we won’t need in the middle of the night (luckily, I don’t). Then we pull the cords of our sleeping bags into a tight cocoon. Only our noses stick out.

Each of us dons eye covers to block out the light and earplugs to mute the snores and howling wind. But we can still hear the Snowy Owls—a group of executives and soldiers from Quebec—happily bellowing Charles Aznavour songs in their tent. “You are the one for me, for me, for me, formidable” echoes in the night.

Demon barks, and we rip off our eye covers. The big dog stands guard against the polar bears that roam the North, and Nansen, who keeps a gun beside his sleeping bag, just in case, had told us to wake him up if he ever howled. But it is now 7 a.m., and Demon is only playing the part of rooster.

Our tent is flapping furiously in the wind. The water in the bottles beside our mattresses is rock solid. The roof is covered with frozen condensation. But we drag ourselves out of our warm bags to prepare for the day’s 18-kilometre hike.

Like everything else here, breakfast takes an inordinate amount of time. Before we can cook our oatmeal, we have to carve a block of snow, stuff it in a bag, bring it into the tent and set it to boil on the gas burner. We are a disorganized lot. Drying out and rolling up our sleeping bags, folding our mattresses and preparing our small lunch bags in a crowded space where, somehow, everything disappears tests everybody’s patience. Luckily, most of my teammates are in good spirits after a solid night’s sleep. Not Lennox—he looks jittery; he got so cold in the night, he woke up in a panic and had a hard time getting back to sleep. He’s not the only one. And as we heave our backpacks onto our sore shoulders, they don’t feel one pound lighter than they did the day before.

The civilians on the trip have trained for months to ski in this inhospitable climate. Bruce Rothney, president of Barclays Capital Canada, tells me he lost 20 pounds to reclaim a physical form he hadn’t known in years. Aghar exercised with a bag full of rocks to simulate a loaded backpack. Labrecque snowshoed and cross-country skied in the backcountry near Mont-Tremblant. Boyko is an experienced expeditioner who has ascended Mount McKinley in Alaska, Kilimanjaro in Tanzania and Aconcagua in Argentina. As for the Desmarais, they braced themselves by sleeping on the porch of Paul Jr.’s condo in Tremblant, with no tent and with the lights on. They scurried back inside at 3 in the morning, when a snowstorm hit and their mattresses deflated. But they tried again. “We don’t give up,” says Paul III.

But even the most trained among us weren’t prepared for trekking days that would stretch from 10:30 until 6 or 7. After two days of hard, flat ice, we’re navigating between beautiful mounds of the stuff that jut out from the surface of the frozen sea. We cross fresh polar bear tracks—a mother and her cub. Then we ski uphill, in a riverbed on Ellef Ringnes Island, in a long, 21-kilometre stretch. Protected from the wind, we are warmed by the sun, at last. Like kids, the two Dans on my team take off their skis and toboggan down the hills on their sleds.

Some trekkers trudge along in silence. Others strike up conversations with people outside their herd, to take their minds off of the hardship. One day, I catch up with Dougal Macdonald, president of Morgan Stanley Canada. When he alludes to SNC-Lavalin’s sale of Alberta electricity transmission company AltaLink—a deal that will be unveiled within days—I kick myself for having left behind the satellite phone I decided was too heavy.

Another time, I catch up with François Olivier, the son of a Quebec provincial police officer who played for the Boston Bruins’ farm team before trading his NHL dream for a hockey scholarship at McGill. When Olivier started at Transcontinental 21 years ago, printers were, well, printing money, and the Internet was still a curiosity. Today, TC’s printing and media businesses are limping, and Olivier is searching for growth. Flexible packaging is the company’s latest venture; it’s a tricky one, given cautious food-industry clients and strict sanitary rules. “Like with this trip,” Olivier tells me, “we are facing a lot of unknowns.”

The real talking happens back in our tents, where we confide our life stories in a parody of one of Quebec’s most watched television shows, Tout le monde en parle, renamed Toute la tente en parle.

One evening, Bruno Guévremont, a bombs expert, recalls chillingly how he once had to remove an explosive vest from a Taliban fighter who’d chained himself to a fence; it was a suicide mission to kill Ahmed Wali Karzai, one of the president’s half-brothers. All Guévremont had was tape, a pair of wire cutters and surgical scissors. He survived, obviously, but the stress of the mission, where his bomb squad was always on call, has taken its toll. Even in Resolute, population 230, crowds make him feel uneasy. He’s moving on, though: The leading seaman just retired from the army at 39, and now works as a cross-fit trainer in Victoria.

After three days, a sense of normalcy settles in—no one cares any more if everyone sees them in their undies. But just when we think we’ve got the hang of this trek, there is a twist. We run into a group of Canadian Rangers who patrol the Arctic. They’ve been ordered back to safety in Resolute, a two-day snowmobile drive, to take cover before a big storm hits. That same system means we’ll have to reach the pole a day early, to weather out the tempest in our tents, protected from the wind by igloo walls we’ll have to hack out of the snow.

That means our last skiing day will also be our longest: 24 kilometres. After what seemed like a full day of climbing, we’d all fooled ourselves into believing we’d be heading downhill, but the long slide never materializes. And it feels colder than any of the other days we’ve been up here. It is past 7 p.m. when we finally see it: On the top of a snow pile, the Rangers have planted a Canadian flag. Our goal is within 500 metres.

B is overcome by emotion. He’s brought some keepsakes to bury in that mound: a photo of Bob Gilmour, the former downhill racer who taught him how to ski after his recovery, but who died last December; some of his ashes; and a Post-it note on which he has jotted down one of Gilmour’s mantras—a passage from a Kevin Welch country song:

There is gonna be two dates on your tombstone, all your friends will read them

But all that’s gonna matter is that little dash between them.

Beside B, the rest of his teammates pose for a final photo, their faces lit by the sun, looking south for once. Among them are the Desmarais, father and son, standing arm in arm—like a dash between them.