A few hours before dawn on April 17, 2010, Kenneth Irving, a favoured son in Canada's third-wealthiest family, and the CEO of a multibillion-dollar energy empire, sat at the kitchen table in his forest-framed mansion outside Saint John. His wife and two youngest daughters were sleeping upstairs. From the windows of his house, he could see the grand sweep of the Kennebecasis River and the pine trees that he liked to plant in the mornings before heading off to Irving Oil, to take his place in the onetime office of his storied grandfather, K.C. Irving. By every standard, Kenneth knew he was a lucky man. And yet, alone in the dark, all he felt was anger and despair.

He doesn't clearly remember raising his fist. He does remember that the pain was intoxicating. Later, he would tell one of his daughters that he took out his rage on the one person he blamed for his problems. He swung hard, over and over. He punched himself in the eyes until his sockets were a deep purple, until blood vessels had burst and his knuckles were raw.

His wife, Tasha, woke at 5 a.m. to an empty space beside her in bed, and raced downstairs. She found Kenneth, slouched over the kitchen table, his hands holding his head. He lifted his face to look at her. "Did you fall?" she asked, though she knew he hadn't. He shook his head. She got on the phone to call for help.

That was the last night Kenneth Irving would spend in the house he had built beside the river he loved. He would never sit again behind the desk that had been handed down from K.C. to his second son, Arthur, and then to Kenneth. He has returned only twice to Saint John, the royal seat of the Irving empire, and then only to pack up his house and finalize the donation of the 50-acre estate to an environmental non-profit.

Kenneth Irving’s $2-million home in New Brunswick was donated to serve as a national centre to protect Canadian waterways. Read Paul Waldie’s 2013 story about that donation here.

HANDOUT

Later, that life-altering day, after Tasha did her best over breakfast to distract their daughters from their father's bruises with a well-meaning fiction about bumps in the night, after Kenneth's psychiatrist arrived from out of town and insisted his patient be hospitalized for his own safety, Kenneth was driven to the airport. Along the way, he insisted on a detour – one last visit to his family's refinery, just up from the harbour on the city's east side.

As CEO, he had liked to go to its central control room sometimes, late at night, to watch the computer screens, listen to the two-way radio chatter, and discuss conversion rates and temperatures with the plant operators. He shouldn't have gone this time – "What the hell was I thinking?" he says now – not looking the way he did. He says he wanted his doctor to understand this part of his life. Perhaps he also wanted to be with the engineers and technicians he so admired before the chance slipped away for good. He gave his doctor a quick tour, and feebly joked about an errant walk into a door, which fooled no one. Then, he left for Boston, because an Irving could not be locked up in a psychiatric hospital in New Brunswick. "That was it," he recalls. "My last day on deck."

Some of this story is known. It's been the subject of newspaper columns and book chapters. But in a sturdy, tight-knit province where the Irvings keep the lights on but store their secrets safely in the shadows, most of what happened that day, and the echoes that followed it, is the stuff more of rumour than fact. With a private fortune estimated at $8-billion, the family owns New Brunswick's three major daily newspapers, radio stations and a chain of weeklies. The Irving empire includes everything from shipyards and refineries, to pulp mills, railway lines and convenience stores – the family's name stamped, in tall navy letters, on what seems like nearly every money-making enterprise in one of Canada's poorest provinces."The Irvings are a fact of life," says Hugh (Ted) Flemming, the MLA for Rothesay, the riding next door to Saint John. "Like the Bay of Fundy, they are big and deep and they aren't going anywhere." A Senate report once estimated that Irving companies employ one in 12 people in New Brunswick. But you don't have to work for the family to be tied to its fortunes – or to have an incentive not to speak too freely about the sudden, shocking disappearance of an Irving son.

Kenneth was well-respected, seen as a modernizing, innovative force within the family's third generation, an Irving with a worldly gaze and big plans to expand and diversify the energy business. But in the wake of his leaving Saint John, there were also whispers that challenged that narrative. Whispers that Arthur Irving, reluctant to fully cede power, had been unhappy with the business direction that Kenneth was taking, and fired his son. That there had been a fight over money. That the stress of the job – and all that went with it – had caused Kenneth to suffer a mental breakdown. But those are pieces of the tale, patched together from fragments of truth to quilt a tidy narrative.

There is a much darker version of these events, one Kenneth Irving has never told before. He is offering it now, in part, as a cautionary tale about waiting too long to seek help for a mental illness. You may wonder about that: What can a man as rich as Kenneth Irving say to those who have to wait in line for care, who can't afford a full-time psychologist, who have lost their jobs because they were too sick to keep them, and don't have a trust fund? To his credit, he is quick to acknowledge this: He's not, he says, looking for pity.

What he seeks is understanding. He hopes that someone will see past the shiny objects that come with being born into the one per cent of the one per cent – the boarding school education, the private jet, the sprawling estate – and find a lesson in his story.

"I was born into this incredible situation. That is what is so strange about it. That is what is so hard to accept. That you are going through this when you know you are so fortunate in every way."

Kenneth Irving with his grandfather, K.C. Irving, at a refinery circa 1990.

HANDOUT

Even as a little boy, the eldest son among four siblings, Kenneth understood the path before him – the responsibility and obligations of being an Irving. When he was 6, he remembers, his grandfather taught him how to shake hands, and how to use the radio in the truck to call into one of the family's myriad businesses. "Paper mills and shipyards and oil refineries on the weekend with my grandfather," he says. "That was my life, and I loved it."

K.C. Irving was well known for being frugal and a teetotaler, characteristics that he impressed upon his three sons, J.K., Arthur and Jack, who would each focus on their own fiefdoms in the empire. It was a formal family, one in which emotional indifference was viewed as a strength, handshakes stood in for hugs, and deference to elders was expected. Problems, business and personal, if they were discussed at all, stayed inside the Irving fold. The family name brought privilege and respect, but also obligation and adherence.

At 17, Kenneth was called by his grandfather to a private meeting, where it was proposed that he take K.C.'s own middle name, Colin. He added it legally in 1983, and uses it today in his e-mail address. "It was one of the proudest days of my life," he says, a sign of approval: that preserving the meaning of those initials now fell to him.

If K.C. was a lodestar in Kenneth's life, the situation was less stable at home, where, by the time Kenneth was a young teenager, his parents were beginning the path to a hostile divorce. From Grade 9 to graduation, Kenneth attended Lakefield College School, a private boarding institution in Ontario. His younger brother, Arthur Jr. later joined him at the school. His older sister, Jennifer, went to boarding school in Switzerland. Emily, the youngest of the four, would move with their mom, Joan Carlisle Irving, to the West Coast when the parents made their split official in 1980. When discussing his life before he became sick, Kenneth rarely mentions his mother. She remarried in British Columbia, and the bitterness between her and his father meant he had little contact with her.

Starting in high school, Kenneth spent only short stints in Saint John. He worked most summers away, taking jobs as a labourer, such as baling hay and cleaning turkey barns. Later, he attended Bishop's University in Quebec, studying social science, and acting in plays. On school breaks, he worked entry-level jobs for Irving Oil – his resumé includes such titles as underground petroleum-tank operator and lubricant-packaging-and-production-line worker. In his last year of university, he begged off an economics final to get a gig as a roughneck on an offshore drilling rig headed for the cold waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

A few years later, he moved to Alberta, to work with Chevron, a company then partnered with Irving Oil, for a management-training program designed to give him front-line experience. He spent time as an assistant to the geologists in Calgary, and was later sent up north, to places such as Slave Lake and Aklavik, to the drilling rigs. "It wasn't glamorous work," he says, although his voice lifts when he talks about those experiences. "There wasn't really a game plan for me. I had to make my own way." But it was expected that he would soon take his place at Irving Oil headquarters – what locals call the Golden Ball.

By 1988, he had his own cubicle at Irving Oil, and was living in an apartment in the south end of Saint John. He became close with his father. They shared hotel rooms when they travelled for work – "to save a buck," Kenneth says, laughing. In June, 1993, Arthur stood beside his son as best man when Tasha, a teacher and pianist from Vermont, walked up the aisle in a ceremony at her family's home in Bennington.

They spent time duck hunting on Arthur's secluded, lakeside property in Hampstead, N.B., and later worked together to design a beach house for Arthur on the Bay of Fundy. Kenneth and his family would regularly attend parties hosted by Arthur and his second wife, Sandra. Kenneth's friends would make the invite list for the annual summer BBQs. True to Irving practice, alcohol was not served at those events – a rule Kenneth respected in his father's presence, although he enjoys a beer with friends. According to Andrew Rouse, a Fredericton lawyer and long-time friend to Kenneth, Arthur was a generous, if reserved, host. "He is not a guy who will sit down and talk your ear off," Mr. Rouse says.

In 2009, Kenneth named the holding company for Irving Oil after Fort Reliance, the national historic site in the Northwest Territories where he and his dad had gone canoeing. "Those are good memories," he says, of his erstwhile relationship with his father. "I don't want that part of my history to be rewritten."

Families are complicated enough when the members make their own way in life; they often become immeasurably so when business binds fortunes and futures. (Ken's eldest daughter, Starling, introduced her dad to Arrested Development, the TV show about a beleaguered son trying to run a family business. It was, he says jokingly, "very inspirational.")

When K.C. Irving died in 1992, leaving his sons to manage the dynasty that he had built from a single sawmill and a car dealership, and to navigate its complex, overlapping operating structure, controlled by a trust in Bermuda. Over the years, the brothers had assumed distinct roles in the empire – Arthur took over the energy side; J.K., forestry and shipbuilding; Jack handled real estate and construction.

The brothers had their differences, and as each of the third generation settled into its management roles within the company, the clash of business interests and personalities only sharpened. In November, 2007, in an exclusive interview with The Globe and Mail, J.K. Irving confirmed that the three brothers were working on breaking up the family conglomerate. It would mean that the cousins, particularly the two heading the biggest pieces – Kenneth, at Irving Oil; and Jim Irving, J.K.'s eldest son, who was running the forestry enterprises – could manage their interests independently. Dissolving the K.C. Irving trust, according to a court document, cost "in the region of $100-million" in legal fees alone. Ensuring that each brother received what could be deemed a fair share required a team of lawyers, hashing it out offshore.

The fate of the company as it passed to the third generation weighed heavily on Kenneth's mind. Mike Crosby, an American executive recruited to Irving Oil by Kenneth in 1999, recalls how he often talked about the so-called founder's trap, in which companies created by a powerful patriarch crumble by the time the grandchildren take over. Kenneth, says Mr. Crosby, "had this huge legacy business that's got his name on it, and he didn't want to lose it as the third guy on the watch."

As CEO, Kenneth began recruiting outside managers, and shifting the culture at Irving Oil. The company replaced rusted tanks and old trucks, made improvements to its convenience stores, and embarked on a major retrofit of the refinery itself. (Canada's largest, the refinery produced 320,000 barrels a day.) Time and money went into leadership training and employee engagement – including raising salaries to industry standards – and much-needed repairs, such as the addition of air-conditioning to the aging headquarters, which had been built by K.C. in the 1930s mainly to serve as a parking garage for his Ford dealership, and was remodelled into offices two decades later. As Mr. Crosby puts it, "It was like we were in the middle of his dad's house, and while his dad is still living in the house, we were tearing down the walls, adding additions, repainting everything in the rooms. We were transitioning the company to the next stage."

Between 2000 and 2008, the value of the company, using a benchmark developed by Deloitte Consulting, doubled twice over, says Mr. Crosby, who left shortly after Kenneth's illness, is now the executive vice president of Land America's at World Fuel Services. "That's the story that doesn't always get told," he says. The achievement, Mr. Crosby recalls, was celebrated at a management meeting during the summer of 2008, in Wolfville, N.S., at Acadia University, Arthur's alma mater, in the building that bears K.C. Irving's name.

That same year, Kenneth officially moved into the mahogany-panelled office once occupied by his grandfather, with the wall compartment that concealed a private washroom. He says he felt invigorated by the challenge of running what was considered the sweetest piece of the dynastic pie. He had ambitions to invest in new technology and grow an energy hub on the East Coast. "I had a really special job," he says, "and I was able to do it well." He is described by several former employees as inclusive and socially conscious, eschewing work titles for team-building and collaboration. As CEO, he favoured "360" performance reviews, in which the boss is also confidentially critiqued by those reporting to him. "I wasn't," he says, "a command-and-control type of personality."

Still, he wasn't above a tough negotiation. Under his watch, Irving Oil swung a large – and controversial – discount on the property taxes for a new natural-gas terminal, to loud objections from the public. (In December, the provincial government passed legislation to rescind the tax break.) Kenneth was also keen to expand Irving Oil's reach. In 2009, he opened the company's first Toronto office. And he was interested in alternative energy: The company began exploring the possibility of extracting power from the legendary tides in the Bay of Fundy.

"Kenneth understood the energy business at a very strategic level, and he networked a lot," says Mike Ashar, who was recruited to become Irving Oil's chief operating officer in 2008, after a 20-year career at Suncor. (Mr. Ashar would oversee the day-to-day operations at Irving Oil, while Kenneth became CEO of Fort Reliance; when Kenneth left the company, Mr. Ashar was formally appointed as CEO by Arthur.) Although Mr. Ashar would ultimately have his own legal conflict with the Irvings – and declined to speak to The Globe and Mail about any other member of the family, or the events of 2010 – he was more than willing to discuss his opinion of Kenneth: "I joined Irving Oil," he says, "because of him." He found Kenneth progressive, and easy to work with, not someone to toss around his Irving name.

"He had a vision," says Mr. Ashar. "It is very hard not to like him as a person."

For the most part, sources say, Kenneth sheltered his new management team from any simmering family tensions. But playing out behind the scenes was another narrative, one driven by an aging patriarch, strong personalities, and competing visions. Kenneth's sisters did not have a business role with the company; his brother, Arthur Jr, worked on brand development and managed the real estate. One former employee recalls that sometimes, during management meetings with Arthur, Kenneth and Arthur Jr., members of the executive team would be asked to leave the room. They would sit outside, on at least one occasion for three hours, while the conversation clearly turned heated behind closed doors. "Ken would always be very apologetic," afterward, the source observed. But the cracks were beginning to widen under his feet.

Even after Arthur handed the reins to his son, say sources connected to the company at the time, he made random appearances in the office, micromanaging even relatively small decisions such as, for example, those involving office renovations. "His father never got out of the way, didn't really let Ken run the business, and that became a crisis in the end," one source recalls.

Three sources, speaking on background to The Globe, describe how Arthur Irving was quick to show his frustration, raising his voice in meetings to openly contradict or berate Kenneth, exhibiting little regard for who was listening. "I have never seen anything like it [in a corporate setting]," recalled one source. "He didn't hide his disdain for the path we were on."

Expanding Irving Oil required resources – and risk. But by 2009, oil prices had collapsed, and the economy was in recession. Running a company whose main source of profits was its massive oil refinery and its gas stations became significantly more challenging, a problem not unique to the Irvings.

In a well-publicized partnership with British Petroleum, Irving Oil had announced that it was exploring plans to invest in a second refinery outside Saint John. The deal, worth $7-billion, was cancelled in 2009 as refineries in North America and Europe cut operations. With it went thousands of anticipated construction jobs for New Brunswick. "It's not the end of the world," the province's finance minister said at the time. But it was certainly a crushing disappointment for a struggling region of the country.

In May, 2008, Irving Oil had also announced a research project with a local marine-science centre to explore 11 possible sites for generating tidal power on the Bay of Fundy – an alternative energy the company was not alone in considering. In June, 2010, not long before Kenneth's leave of absence was announced, the project was cancelled. There were also plans to build an upgraded, $30-million headquarters for Irving Oil at Saint John's Long Wharf, a proposal that had become controversial because the port workers' union objected to using wharf space for offices. This, too, was cancelled, in February, 2010.

Companies investigate and then abandon new projects all the time – for sound business reasons, or because of changing economic conditions, or simply because the exploratory research doesn't support proceeding. Still, sources say that these examples became points of tension between Kenneth and Arthur, who felt – sometimes in hindsight – that his son had taken unwarranted gambles.

Meanwhile, there was indeed a fight brewing over money.

In late 2009, on the heels of the breakup of K.C. Irving's empire, Arthur Irving was working to set up a trust of his own, one worth $1-billion, with quarterly distributions going to himself and his children, along with provisions for his grandchildren. The trust would pay dividends from the profits of Irving Oil. In subsequent years, a rumour grew across New Brunswick that, given his professional contributions to Irving Oil, Kenneth had objected to receiving a share equal to that of his siblings, who had been less involved, or not at all, with running the company.

In fact, says one source with knowledge of the events, Kenneth was increasingly concerned that the trust's payments to family members would drain Irving Oil of revenue that it might better reinvest into its operations and future expansion . This position, the source says, put him at odds with family members.

"The stress was tremendous," says one source, referring to the difficult months in 2009 and 2010. "He's running this huge, complex business, and he is being attacked by his family on every single issue. Like, even though we were performing well, we should have tripled the business. Nothing was ever good enough."

And while the tension between Arthur and Kenneth was a poorly kept secret, few people truly understood the toll it was taking on Irving Oil's CEO, whose depression was deepening. His distress came to a head late one night in January, 2010, when Kenneth called Tasha from a hotel room in Toronto. He was worried about what he might do to himself.

"Don't leave me alone," he begged her. Tasha understood the meaning behind his words. She called one of his best friends, Greg Thompson, a banking entrepreneur who lives in Toronto and had known him since university. Greg headed to the hotel and sat up with Kenneth until he could fly home to be with Tasha the next day.

"Guilt is where it starts, and then it's just total disdain for yourself. Total loathing. It is a terrible cocktail – despair, hopelessness and loathing. It just completely consumes you."

The first time I met up with Kenneth Irving was in early November, in a meeting room at the Royal York Hotel in Toronto. He brought Alison Hall, who had been a nanny for Kenneth and Tasha's younger daughters when she was at Toronto's Ryerson University. She is now a TV producer with Inside Edition in New York, and it was her that Kenneth first approached to tell his story.

Ms. Hall interviewed Kenneth on camera – a personal video that was funded by him but edited independently by Ms. Hall and then shared with The Globe and Mail. (You can watch the video below.) Ms. Hall being both a family friend and a journalist, Kenneth requested she serve as the family intermediary with The Globe throughout the project, facilitating follow-up interviews and fact-checking. She did not participate in the interviews, or direct the line of questioning.

I interviewed Kenneth in person for six hours in total, including at a second meeting at the Royal York, in December, at which Tasha and Starling also spoke with me. In addition, I communicated with the family repeatedly by e-mail, filling in gaps in the story, or with Starling and Tasha sharing memories of their experiences together. I also conducted several follow-up interviews by phone with Kenneth.

Additionally, The Globe and Mail reached out multiple times over several weeks to Arthur Irving, leaving messages at his home, and making calls and sending e-mails to both communications and legal staff at Irving Oil. No response was received.

The first time I meet with Kenneth Irving, he is dressed in a plaid shirt, his eyeglasses – the arms are bright mustard green – hooked over a shirt button. It is the casual-chic uniform you'd expect of the co-founder of LUUM, a transportation tech start-up based in Seattle, an oil field away from the suit-and-tie CEO he once was.

Kenneth is a rower and he looks the part: tall, lanky and clean-cut. He is not what I was expecting. I once worked as a journalist in New Brunswick, and the Irvings were known for carefully cultivating a folksy, down-home, billionaires-on-a-budget image. Kenneth, now 55, comes across as warm, polished and a little nerdy – a man who can wax poetic about the meditative qualities of a river at sunrise, and leap into an animated conversation about city traffic. And, of course, in a direct abrogation of the Irving ethos, he is opening up his life to a stranger.

Kenneth wants this to be his story, and his alone. He sees the telling of it, this baring of his soul, as an act of independence, a way to heal, to be seen as an individual, and, he hopes, to help others. "I don't want to antagonize anybody," he says. "That people believe that I am sincere, that I don't have an ulterior motive, is incredibly important."

In our interviews, he takes his time answering questions, speaking thoughtfully about the nature of his illness, like someone who has spent many hours in therapy. But for all his apparent ease and candour, he often seems to be holding back on details, like someone reaching a dead end in a maze and pivoting in a new direction. That's not unusual; people always tell their story as they want it be known. But it's clear there are extra layers of complexity here: He obliquely suggests that he is navigating legal constraints, as well as personal ones.

When asked for details, he tends to fall back on metaphor. I point this out at one juncture, and he offers yet more metaphors, referring to the "tripwires and land mines" that he is trying to avoid. Asked, for instance, about the circumstances of his departure from Irving Oil, he takes a couple runs at an answer that is ultimately not entirely revealing. Finally he offers, with evident frustration, "I don't want to play games or be evasive, but you can imagine all the ways that I am constrained."

In that case, I ask, wouldn't it be easier, safer, to just stay quiet? Perhaps, he says, but there has to be room for his voice to be heard, and he no longer wants to leave others to shape the Kenneth Irving narrative.

When he was 25, Kenneth says, he had his first bout of depression, although he didn't truly understand the symptoms at the time. He was working as a roughneck on an offshore rig – doing well, he says, proving himself, making friends, living away from under the weight of the Irving name. But he was heading back to Saint John, he recalls; and as the return date approached, he was unable to sleep, and "just feeling constant dread."

Once in Saint John, single and living alone, the dread grew stronger. "It was really rolling," he says. "I was just getting up at night, feeling total despair, and not knowing who to talk to." His fragile psychological state manifested as an irrational fear that he was physically sick – that he was dying, that maybe he had cancer, or even AIDS. Finally he saw a psychiatrist, who prescribed medication, which he took for a while, though it made his legs shake, his mouth dry, and working difficult. Looking back, he describes this time in his life, struggling to heal mostly on his own, as his "first real experience with loneliness."

Over the next year, with treatment, he recovered. He left Saint John soon after, heading out to Chevron and Alberta. But always, the city – and his responsibility to his family – pulled him back. Not long after returning to Saint John again, he left a voice-mail message on Tasha's phone, and kick-started their romance. The two had met 10 years earlier at university, through a friend. When Kenneth learned through the same friend that Tasha was living in Boston, he decided to call her.

As Tasha tells it, she heard his voice on the answering machine and "I burst into tears. I turned to my sister, who was my roommate at the time, and I said, 'I am going to marry this man.'" After a period of long-distance courting, she joined him in New Brunswick. He surprised her with a Steinway grand piano on the night he proposed, in the living room of their first home in Saint John's north end.

After their second daughter was born, the couple designed and built their dream home on the river. Tasha started an independent co-operative elementary school called Touchstone Academy, in Rothesay, a suburb of Saint John, which currently enrolls nearly 100 children a year. They have four daughters – Starling, now 22; Rein, 19; K. Leigh, 17; and Willow, 14.

Kenneth typically spent more nights travelling for work – meeting crude-oil suppliers in London, for example, or raising investment money in Dallas – than he did at home. To relax, he rowed, or planted trees in his backyard, or listened for hours to Tasha play her Steinway. They are a tight family: To celebrate her father's birthday last year, Starling made a Facebook list of the lessons he had taught her. Among them: Stack the plates before the waitress clears your restaurant table. Do three slow rotations for the perfect roasted marshmallow. Marry someone who makes you laugh.

No matter what else happened, Kenneth says, his wife and daughters were his solace. "I never dreaded coming up my driveway."

The first sign of trouble, he says, started toward the end of 2009: He began to notice that his speech would suddenly slow, that his mind would drift; he had trouble staying focused. He describes the early signs as akin to the twinge in your leg just before you pull a muscle. "That was the beginning of it," he says, "and from there it just got very, very dark."

At home, Tasha noticed that when Kenneth seemed more stressed he would sometimes come home from work and watch TV instead of talking to the family. "You could see he just had his own thoughts," she says. "And it was harder to get him back." He wasn't sleeping well either. She knew there was tension at work, and that the situation with his father wasn't easy. But she took comfort in the fact that the dark periods always lifted – some days, he would be just fine, engaged, joking, typical "Irv," as she and his closest friends call him.

When he was away from his family, though, on the road for work, and alone at nights in hotel rooms, Kenneth himself recalls, his depression and anxiety worsened. "You just have these grooves that are such deep trenches in your mind, that if you get on one thought pattern, it is hard to get out of those ruts."

To distract himself from such thoughts, he created rituals. He would lay out his clothes for the next morning, and unpack his toiletries in the bathroom in a certain way. He would order room service even when he wasn't hungry. And then, as the evening wore on, and with no other choice, he would try to sleep. "Quite often that wouldn't happen, and it just got worse and worse."

Over time, he started thinking about killing himself, he says, a secret he carried alone, because he felt ashamed.

"I was deeply confused," is how he puts it now. "I was coming home to someone I am deeply in love with, and yet I was finding peace in the idea of the ultimate betrayal." He said nothing for weeks, not to Tasha or anyone, hoping it would pass. Nine years earlier, at 40, he had suffered from angina, and travelled to Boston for treatment – implicitly understanding that an Irving should not make such problems public. It was a lesson he could not now shake: Keep your weakness to yourself.

But in January of 2010 – calling Tasha from that Toronto hotel room, begging her not to leave him alone with his thoughts – he finally acknowledged that he'd already waited too long to seek the support of those who loved him.

After that night, Tasha made sure that, wherever her husband went, he was not left alone for long periods. He continued to travel – going with Tasha to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, at the end of January; and with a colleague to the Winter Olympics in Vancouver. But Kenneth was struggling, Tasha recalls. By mid-February, she found him a psychiatrist in Boston and he started a treatment regime that involved medication and talk therapy.

At that time, Kenneth explains, he wasn't in the office as much – the refinery was in the hands of Mike Ashar, and he was setting up Fort Reliance, the holding company. One of his goals was to create a corporate structure that would allow the management team to operate at arms-length from the family shareholders. On work trips, he would make detours to Boston for therapy appointments. He was still, he says, refusing to admit how sick he was. "I thought, 'Okay, I will just take some pills, they will help me sleep, I went through this before, I will just power through.'"

But, as the early morning of April 17 would demonstrate with a force he did not see coming, he'd been only barely holding the black dogs at bay.

"I am always taken by those studies on lab rats, like the one on intermittent recognition and just how addictive that is, and how a rat can hit a little panel, and get a shock and get a niblet at the same time, and then hit the panel, get a shock and get a niblet, and then hit the panel, get a shock, hit the panel, get a shock, hit the panel, get a shock, and then get a niblet. And if they space it out wide enough, the rat will kill itself, in the hope that they are going to get something … I never felt like a rat, for the record. But I don't think we should think of ourselves as beyond nature. Some of our needs are pretty basic."

It is here in Kenneth Irving's story that a villain would seem primed to appear. And although it's true that Arthur Irving is an ever-looming influence in his eldest son's life, Kenneth refuses to lay blame on his father for his depression. Even after everything that has happened since, he describes an intense love and respect for his father.

"I am the product of my dad," he says unequivocally, in a reflective tone that suggests he has come to own the complexity of that statement. "However it turned out, however it came to be, I like where I am at, and he has to be given credit for that."

But at the same time, he also describes their relationship as problematic: a demanding father, and a son twisted into knots, consumed with gaining his father's favour; both men existing in a tightly contained family system thin on encouragement, and impatient with human error.

When in the office, Kenneth tells me, he often walked "on eggshells," always "trying to please someone else." As he went about the tall job of running Irving Oil, he spent many days trying to accomplish what felt like an impossible task: to figure out what his father wanted, working overtime "to win his approval," only to feel, constantly, that his efforts fell short.

As he became more depressed, and more suicidal, he says, "I doubled down on my commitment to understand what my dad wanted and to meet his expectations." That only made his depression worse, he says.

At one point he asks me, "Have you ever heard of gas-lighting?" – a pattern of behaviour of where one person convinces another to believe a false reality. "I just learned in retrospect," he continues, "that that was a common theme with a lot of people, that gas-lighting isn't just something they put into the movies to make it extra scary. Some people actually experience it and don't know it." Perhaps the person doing it, he notes, isn't even conscious of their actions. But the result for Kenneth was that he felt "very disoriented … and when that started to happen, I thought, 'I am going to let down a lot of people, especially my dad.'"

When pressed for specific examples, he demurs. "It can be blatantly obvious and it can be insidious. It can be ambient. People can be in the room and not even know what is going on. The only person that really knows is the one who is in [the relationship]," he says.

It didn't help, he says, that for all its perks and as much as he loved his hometown, being an Irving in Saint John can also be emotionally isolating. The head of a company can't chat about his problems at the water cooler or the lunch table. "Once I went to work, I was on point all the time," he says. "If I went to a restaurant, or just driving my car down the street, I felt like I was on point."

But the problem, he insists, was not caused by the standard pressures that come with running a huge enterprise, or the weight of his family name – two responsibilities he seized with enthusiasm. "I felt energized by the people there, and the work that I was doing," he says. Besides, he claims, the company was still doing well despite a difficult economic climate, even as he himself was starting to feel his worst. "I am quite satisfied," he says, "that I left the company in very good shape." This view is echoed by sources familiar with the business side of Irving Oil.

Yet, he refuses to blame his father for all the darkness that visited him. That would be too simple, he says. Rather, he points to what he perceived had become a destructive relationship between two people, and the environment in which it existed. If any one person is to blame, he says, it is himself. If he saw himself as he believed his father did, that was his fault – for also expecting too much.

"Whatever part of my life was successful, it didn't bring the right response … and perhaps, I have to admit, I put too much hope in that. It was meaning, literally, the world to me. And my world came crashing in when I knew, or some part of me started to learn, that I wasn't endearing myself by being successful. I put my heart into everything because that is the way I am wired, but I also felt that I would do my dad proud."

He had inherited the gilded cage of a wealthy scion. "I was given broad opportunity," he observes, but was "pushed into looking at the world in a very narrow way." That environment, he says, "when you are in it, is very hard to see. It is even hard to see things that most people consider abuse."

One day, if you're lucky, you wake up. As he puts it, later in our second interview, "Eventually, the rat wants to know if he is getting a shock or a niblet."

He talks about having lived his life twice – once through the eyes of someone else; and now, after therapy, through his own eyes. Looking back, he says, "I just can't believe I had such a distorted sense of myself and my sense of worth."

That, he is now convinced, is the path that led to his blackening his own eyes, first, alone in the dark that April night at his kitchen table, and many times after. He was both punishing the person to blame for his misery, and savouring the pain itself. "It brought a temporary relief that was really powerful," he says. It became its own addiction. "I totally understand why somebody would turn to drink or take drugs."

Around the time that he was hospitalized, he says, he received a message, through an emissary understood to be acting on his father's behalf. A source who had contact with the family at the time says that Arthur appeared not to understand the severity of his son's condition, and that he had an old-fashioned view of mental illness, shared by many of his generation – that depression is something a person can shake off, not a medical condition requiring professional treatment.

Since that day in April when Kenneth's life irrevocably changed, he says, he and Arthur have spoken only twice – once in person, months later, in what would be their last face-to-face conversation – and then in a one-minute phone call initiated by Kenneth a few years ago. ( "It was civil," he says, "but I had hoped for more.") Kenneth says he has sent letters, in an attempt to reconcile with his father, but they have gone unanswered.

He won't share what was discussed in their last meeting, in 2010, except to say this: "When my dad left, I knew that was it. When he was walking out the door, he wasn't going to see me again."

"If someone is reading this story, and they're in an unhealthy relationship, and they are feeling, 'Maybe I am going through the same thing,' I really want them to understand that getting out on your own and being independent is the very first step that you have to take."

In Boston, Kenneth was admitted into a locked ward. "I was in one of those places where you go through the door, and it's a heavy door and it closes, and before I went into my room, they took everything from me, my nail clippers and everything else sharp out of my toilet kit, and took my belt, and I remember Tasha crying and I just wanted to lie on the bed and I wanted them to shut the door."

The hospital, Tasha says, was a difficult environment, an acute-care facility that treats patients with severe psychiatric illnesses, such as schizophrenia. With the support of Greg Thompson, who flew into Boston, Kenneth was released into Tasha's care. For a few days they tried to stay in a hotel suite with a nurse present, while he sought help as a hospital outpatient. This wasn't sustainable. Soon Tasha – nicknamed "the sentry" by Kenneth's psychiatrist, for her near-constant watchfulness – was exhausted, and not sleeping herself, and Kenneth was finally admitted to a private psychiatric hospital.

During his first week there, he remembers thinking, "Okay, now they will send me home." He had responsibilities waiting for him. "I had to return to New Brunswick, to get back at it, and I convinced myself that it was not that big of a deal."

But his doctors and his family knew otherwise. He would remain in hospital, for nearly two months, until the end of June. There, he began an intense round of treatment, involving both medication and cognitive-behavioural therapy. "In the beginning, it was just … chair … pen … glass … bottle," he says, pointing to those objects on the table at the Royal York. "That's how far gone I was. You have got to get into the present. I had gone elsewhere."

Cognitive-behavioural therapy is a psychological approach that tries to teach the patient to reframe their thoughts, to notice where their perception of events or people may have distorted their lived reality. One of its chief aims is to provide coping skills, including positive self-talk, to control negative thoughts. "It is incredibly difficult," says Kenneth. "Rebooting your brain is serious work. It is not just flicking the switch on your computer. You have to go back and do some reprogramming, and it is not easy."

He didn't want his daughters to see him in the condition he was in, not least because his ongoing self-harm was evident in the bruises around his eyes – but Tasha suggested that his daughters would want to be involved in his recovery and could handle the truth. The two youngest, being cared for by a rotation of babysitters in Saint John, went down regularly to Boston; Starling and Rein, who were boarding at the Groton private school not far from Boston, also visited. Kenneth's closet friends paid visits, too, occasionally bringing their own children, to walk the grounds with him as his condition improved.

Kenneth Irving with his wife, Tasha, left, and daughters Willow, K.Leigh, Starling and Rein.

LISSY THOMAS

But Kenneth's father, and his extended family, did not come. His daughters, he says, did not hear from their grandfather, and have not since. On this point, Ken is less circumspect in laying the blame where he believes it belongs. "My children needed support, and that is hard for me. If there is one place where I have a different emotion, where I find it disturbing and sad, it's how my children were treated. Because they were just little girls."

He pauses and looks away, as if reeling in his thoughts. "But every family has their dynamics. And it plays out in different ways."

In the meantime, the treatment began to work. He credits the professional care, on the one hand, and the kindness and acceptance of his immediate family and friends, on the other, with playing a big part in his recovery. He participated in group-therapy sessions, listening to teenagers describe their self-image in wretched terms, and thought, "How can they believe this about themselves?" In particular, he still remembers the strength of a mother whose two children had died, and who was beginning to emerge from the trauma of her grief. "If you think you are special and you don't have something in common with these other people, then you are lost," he tells me.

The self-harm continued even as he worked through the depression – the urge to punch himself was hard to shake, like giving up drinking or smoking, and he struggled, for weeks, to stop. "Once you cross over," he says, "you are a runaway train." During our first interview, when I ask him about the self-harm, he pulls out his iPad and shows me a photo. It was taken during his brief stay in the Boston hotel, before he went to the private hospital. Kenneth and Willow, his youngest, are curled up together on a cot. He is looking at the camera, expressionless; his eyes are black circles; his eyelids are swollen, like a boxer who has lost the fight.

"That was not the worst of it," Tasha will tell me later. In private, when he was supposed to be sleeping in the hotel suite, or later in the hospital, he still hit himself. Sometimes his wife would also catch him rubbing at his bruises, as if he didn't even realize he was doing it.

Asked to explain what was driving him to hurt himself, he says, "It is so hard to put into words. Waking up in the morning and having to, literally and figuratively, look at yourself in the mirror and be in that state, where I didn't know what to do. I wanted to do good. I wanted things to be different, but they weren't. And I ended up not being able to process it. I just became overwhelmed with those feelings."

As forthcoming as he is, he struggles to talk about that time. "It is a very dark moment in my life; it doesn't reflect how I generally felt about myself. And it's hard to imagine that something would present itself so catastrophically. It's just, Bam! One morning Tasha wakes up, and sees that I just went … " He says there was no single event that drove him to it, "no particular catalyst."

On the weekends, he attended Starling's rowing regattas, where she was the cox for a men's four. Her teammates would see his bruised eyes, and ask him, "Irv, are you okay?" He would make his fallback joke, Starling recalls: 'You should see the other guy." She waits a beat, like a seasoned comic. "'Cause he was the other guy." She is, just barely, holding back tears.

After one particular visit, Starling remembers that her father broke down, overcome with worry that he was embarrassing her. He wasn't, she says. "I was happy to have him at my races, for him to see this part of my life," she says. "That broke my heart the most – the idea that he could think he was somehow an embarrassment to me."

At the end of June, he was released from the private hospital. He became an outpatient, travelling on the train from Portland, where they had rented a home, and getting off at Boston's North Station, a short walk to Massachusetts General. There, in addition to the medication he was already taking, he had individual, one-hour sessions of cognitive-behavioural therapy. He would often stay for group therapy as well. By the fall, Kenneth and Tasha knew they were not returning to Saint John, and that he was not going back to Irving Oil. They chose instead to go to Toronto.

It took time to get better, he says. "It's not like you suddenly feel, 'Oh, well, the sun has just come out.' It's more like starting to understand things, coming to terms with things. In some cases, it might be giving up false hope." He says he began to grieve the conflict and estrangement with his father as the loss that it was. But "replacing depression with mourning is not something you understand at the time as getting better, because it feels terrible."

He declines to discuss what communications he was having with his father and the people at Irving Oil during these long months. One senior manager recalls that for weeks it was as if the boss had vanished, with no explanation offered. Kenneth also won't discuss the manner of his departure, except to say that at some point, a decision about his future "was put to him." (Sources say that Kenneth initially expected to go back to Irving Oil. But he was asked – and eventually agreed – not to return, the details of his departure hammered out as he continued to recover in Boston.) It was hardly the time to be signing off on a permanent decision, Kenneth himself notes. But, in hindsight, he says, it was the right path to take.

That fall, on a Thursday in early November, his official "retirement" from Irving Oil was announced in a perfunctory press release. The brief, blandly worded statement made note only of his 27-year-history with the company, as if he were any other departing CEO, and not a devoted son and the founding father's namesake leaving the family business. A spokeswoman told The Globe and Mail at the time that the departure "was a personal decision, and one that we will not speculate on."

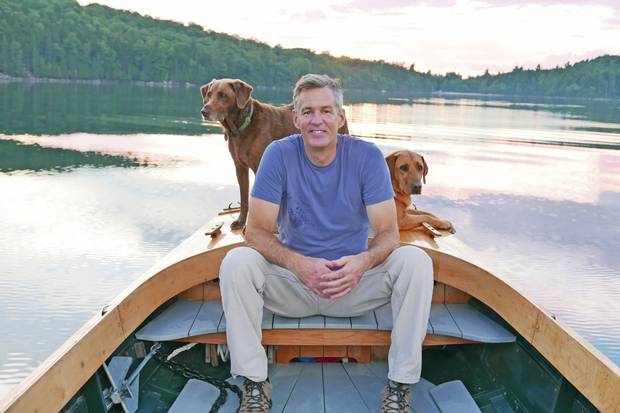

Kenneth Irving with dogs Kuujjua, named after a river he and his father paddled in the Arctic, and Casis, named after the Kennebecasis River in New Brunswick.

STARLING IRVING

"I was brought up, like so many other people, to just think that you suck it up if you're not feeling good, and get out there and get stuff done. And if you are taking a lot of time to go in and talk about yourself, it didn't seem like a very productive thing to do … and clearly I don't feel that way any more. I feel like that is one of my greatest accomplishments – that I somehow found the strength to deal with it, when I thought strength was really found in ignoring it and just sucking it up."

There is plenty to this tale that Kenneth Irving declines to discuss. This includes the rumour reappearing periodically in newspaper pieces and in books about the Irvings: that his departure from the family business, his decamping from Saint John, his fateful rift from the father who was once his best man – that this was all, at the core, the result of a squabble over money. Kenneth will say this much, and he does so forcefully: His illness and his departure from Irving Oil were not related to a "temper tantrum," as he puts it, over any inheritance.

But the messy, emotional relationship between father and son eventually did land in court, and that document is remarkably revealing.

After K.C. Irving's trust was dissolved, Arthur set about creating a new trust, worth, according to the court, roughly $1-billion, the proceeds of which would be distributed among family members. (Kenneth declines to comment on the details of the trust, or the 2012 court ruling in Bermuda.)

The details of the trust are murky, and the court document provides an incomplete picture, but among the recipients were Arthur himself, the four children from his first marriage – Kenneth, Arthur Jr., Jennifer and Emily – and their offspring. (Arthur has another daughter, in her 20s, Sarah Irving, from his marriage to Sandra.)

Arthur's trust took about a year to constitute. It was finalized in December, 2010, the judgment states, the same month that Kenneth was released as an outpatient in Boston; so, certainly a substantial portion of the negotiations occurred while Kenneth was ill. Most of its details are sealed, part of the design of the trust, agreed to by those involved. This includes how much each party received.

In response to questions about rumours suggesting he was upset about his share, Kenneth declines to go into specifics. "But I can say this," he offers, "it is not true … For someone who is looking for an answer, it sounds like a pretty reasonable scenario, if you throw in a lot of other drama. But it's not true."

Most of what is known can only be surmised from the background provided in the Bermuda ruling. In January, 2011, according to the document, a month after the trust was finalized, Kenneth received a negotiated "preferential payment," vaguely noted to be "in the millions." Two sources suggest that this was payment akin to severance, and that Kenneth, having not expected to leave Irving Oil so precipitately, had not received compensation commensurate with a typical CEO's, and had not signed a contract, as is standard practice, detailing the financial terms of departure from the company.

In February, Kenneth filed, through his lawyers, a request for additional information about the contents of the trust. Reading between the lines, and based on his testimony in court, the timing suggests that, now recovered and out of treatment, Kenneth had questions, in particular, about a potential conflict of interest involving the trust's managers, as well as concerns about the management of the funds being derived from Irving Oil. But Arthur fired back with his own legal action, insisting that the contents of the trust be kept secret, arguing that Kenneth, through his lawyer's action, had violated the conditions of the trust – and should have his preferential payment rescinded.

In the end, the judge sided with Arthur on the injunction, but declined to take away any of Kenneth's payment as a penalty. This wasn't about money, Justice Ian Kawaley, now Bermuda's Chief Justice, suggested; it was about family. He noted that Kenneth became "overcome emotionally" on the stand when talking about his break from Irving Oil, his estrangement from his father, and what it had meant for his own daughters. These events, the judge wrote, appeared "to have a greater influence on his present motivations than he was willing or able to acknowledge." The judge described the court challenge as a misguided attempt to open up communication.

In his testimony, which stretched over two days, Kenneth is quoted as saying that he felt he was being "isolated" from information, and said he was trying to do right by his siblings. The judge accepted that the civil suit was not motivated by greed, but was, rather, "to a significant extent based on legitimate feelings of hurt." Kenneth was, the judge said, "seeking to recover a lost extended family and lost working relationship nurtured in a cherished family business which had been brought to an abrupt end."

Although Justice Kawaley sided with Arthur on his main claim – that the contents of the trust were to be kept private – he also cast judgment, of a different sort, upon him. His anger at his son's perceived "disobedience," Justice Kawaley suggested, had blinded Arthur to the possibility that "scars in his relationship" with Kenneth could be healed, as well as to the "collateral damage" that their estrangement was inflicting on other family members, including his own grandchildren.

In his ruling, the judge noted that Kenneth had previously agreed to withdraw his claim, on a few conditions. He wanted a retirement party that would acknowledge his contribution; and to have a family meeting, attended by a professional facilitator, with his siblings, with whom he was not then in contact. He also wanted to attend "a family activity" with his father.

No agreement was reached on these conditions, since the case proceeded to judgment. Although several retirement parties were held, they were thrown by friends, not by Irving Oil. Kenneth has since reconnected with his siblings on his own – he says he now speaks to or sees all three regularly. But from his father, he still hears nothing.

Irving Oil is on its third CEO since Kenneth left. Mr. Ashar, who replaced him as CEO in 2010, left in 2013, and would claim in a lawsuit two years later that he was pushed out of his job early, and not fairly compensated. His statement of claim referred to "many instances of misconduct and inappropriate behaviour involving members of the Irving family that created an intolerance and poisoned work environment." Irving Oil denied the allegations, and the case settled out of court. Mr. Ashar declines to comment on the lawsuit, or to speak about Arthur Irving.

Arthur Irving Jr., Kenneth's younger brother, has also left the company. Sources suggest there is little contact between Arthur and any of his four oldest children. Kenneth's half-sister, Sarah, a recent MBA graduate, is now executive vice-president and chief brand officer, and the rising heir apparent. According to the company website, she is "being mentored by her father, Arthur."

"Where I am in life is a good place … I wouldn't want anyone to go through a dark period in life, but there is a lot that can be learned from it. And one of the things I wouldn't encourage anyone to do is blame somebody for anything that's not a positive. If you are going to find peace, you have got to just accept everything as your own."

At the Royal York, Kenneth pulls out a pair of plastic hearts from his pocket – one, silver; the other, rainbow-coloured. They were given to him by his daughters, who developed a tradition of putting a heart in their father's pocket when he went on a trip, after "juicing it up" with kisses.

"Because today was a big day, I put two in my pocket," he says.

As Kenneth, Tasha and I sit together in a private meeting room in the hotel's business centre, they hold hands under the table. Tasha mostly just listens, interjecting once in a while, especially when she worries that her husband is saying too much, about to utter something that might get him in trouble. She is worried, she acknowledges, about the response that might come from his speaking so openly about the past.

The mood lightens when they tell stories of their "dates" while he was receiving treatment. One night, they ate at a favourite restaurant – it was their second night back in two weeks, and the chef came out to say how happy he was to see them again.

"The only reason he recognized me was because my face was a mess," says Kenneth.

"You were very recognizable," Tasha confirms. "There were funny moments. We could still laugh. "

Kenneth Irving understands that his story, that of an heir to one of Canada's largest fortunes, is not typical. He repeatedly says that he was lucky in many ways, that it's not his intent for people to "feel sorry for him."

But he also wants to join the conversation about mental illness. He hopes his story reaches employers and families, and convinces them that they have to take mental health seriously. He wants his story to be instructive, to perhaps speak to someone caught in a bad situation or relationship, who might then seek help sooner than he did. He has always thought of himself as a "pretty self-aware guy," he says, but "I had to take a two-by-four across the side of the head to wake up and realize that you are not in a place that was sustainable."

He also hopes his story reaches employers and families, and convinces them that they have to take mental health seriously.

Today, he says, life is good. He has a close-knit, loving family, on evidence in our meeting at the Royal York. Of Tasha, he says, "I was dealt my hand of cards. I pulled out the Joker, and, of course, that wasn't fun. But I also married the Queen of Hearts. Not everyone is as fortunate." He lives in Toronto, has a property in Maine, and has been back to Fredericton a few times; but his heart, he says, still pines for Saint John. The family's former 7,000-square-foot home and 50 acres of riverside forest is now a National Water Centre, a retreat for environmentalists and artists.

In addition to non-profit work relating to the environment and the protection of personal data, he continues to focus on LUUM (the name is a play on the word loom, as in weaving people and society together), which has created a platform for businesses to improve the commutes of their employees and promote more environmental forms of transportation. Kenneth doesn't have a formal title – he has an "allergy" to them, he tells me. Instead, he goes by "expedition leader." In an interview, Sohier Hall, the company's CEO, recalled the early days when Kenneth and his team would work on their laptops in a local coffeehouse, surrounded by patrons jamming on guitars and bongo drums. "I remember Ken saying, 'How did I get here?'" Mr. Hall says.

Relations have also improved with the rest of his family. In addition to reconnecting with his siblings, Kenneth celebrated his mother's 80th birthday and communicates with her regularly. Time, he says, has brought a new clarity to those old relationships. "When I came out of the hospital, there were certain people waiting for me," he says. And others, he adds, emerged later. He says he has learned, for the most part, to accept family circumstances that he may not ever change.

"When my time is up, nobody is going to say, 'Poor guy,'" he says. "I don't want this one chapter to be the defining chapter of my life. I have a history leading to up to it, and I have, I think, a wonderful present and future. I have to be thankful for the opportunity I was given, to experience it, and learn from it, and come out the other side."

But toward the end of the interview, as we are wrapping up, I put a final question to him. In so many ways, he has been extremely open. In others, he has been evasive, citing legal restraints. But on one point, I suggest, he is not convincing: that is, when he says he does not care what his father might think of his story.

"I can't think about that," he told me, the first time I asked, in our first interview.

This time, sitting holding Tasha's hand, the answer is different. "I won't crawl under a rock," he says. "If he can't love me," he continues, his voice suddenly cracking, "maybe he will respect me." And then, he weeps. After a moment, regaining his composure, he adds: "My mind can get there. But I don't think my heart ever will."

Suddenly, this feels like the story Kenneth really wants to tell. He is healed and happy. But, even after all that has happened, he is still a son who misses his father. "I would happily meet my dad, any place, anywhere, any time, to talk about anything he wants to talk about," he says.

Arthur Irving is now 86. The time for meetings, the chance to repair what's been broken, is running out.

Erin Anderssen is a feature writer at The Globe and Mail. Follow her on Twitter: @ErinAnderssen

WATCH

The story behind the video

This personal video, produced by Alison Hall, was funded by Kenneth Irving. It was edited independently by Ms. Hall and shared with The Globe and Mail.

Kenneth Irving opens up about his battle with depression and the path to wellness

I met Ken and Tasha Irving six years ago during a difficult time in my life. I was a journalism student from Winnipeg, struggling to put myself through Ryerson University. Midway through my studies, while juggling part-time jobs, I signed up for an babysitting service that was advertised online.

Enter Kenneth, Tasha and their four daughters. From the moment I was welcomed into their home, I was struck by their warmth and strong sense of family values. While I spent countless hours with the Irvings (mostly with their daughters), at first, I wasn't aware of the full significance of the name "Irving," and more importantly, the collective struggle they were all facing. I only knew the Irvings as the family, who included me in their birthday dinners and taught me, among several other important life lessons, the best way to throw a ball for their chocolate Lab. After I graduated from university and started my career as a journalist in New York, we kept in touch over e-mail for a few years.

Last spring, Kenneth approached me, asking for help. Kenneth was ready to tell his story for the first time, with Tasha at his side. Initially, he was focused on his new business; but after several conversations, it became clear to me that the story was about Kenneth's own path to independence. I also knew that if someone of Kenneth's stature could share his story publicly, it might have a profound impact on the lives of other families grappling with mental-health issues. Throughout the process, Kenneth told me that he was willing to bare all if even one person could relate to any part of his story and find strength in their family and friends, but most importantly within themselves.

We decided to work together last summer to create a short documentary. I sought to tell Kenneth's story in its most natural form – as a conversation with a friend. We filmed in an environment that he felt most comfortable – at his cottage in Maine, with a small production crew. Kenneth provided a small budget to cover expenses, but I received no payment and maintained full control of editing. He and Tasha did not see the video until it was completed, and made no changes to its content.

I hope that, after watching our video, someone will feel inspired to reach out to a friend, either to offer support or to speak honestly about their own experiences.

– Alison Hall

MENTAL HEALTH AND DEPRESSION: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

How The Globe’s Niall McGee ended up in a severe, suicidal depression, and found his way back