Some commercial landlords are not betting on prospective tenants’ imaginations.

Kevin Hardy, senior vice-president, portfolio management at Dream Office REIT, a major office landlord, remembers one incident.

A prospective tenant, an insurance company, was being shown various spaces in Scotia Plaza. The office tower is Dream’s showcase, 68-storey, maroon-toned monolith in Toronto’s downtown core. Dream was showing possible office spaces they hoped would suit the insurers, yet the interiors had been designed for law firms, a little on the formal side, corporate feeling, cloistered.

The insurance people had in mind something more open. They lost interest until Dream installed itself in the tower with a floor design for their own offices to model that contemporary look. The insurers were brought back, and they said, ‘If we had seen this, we would have definitely done the deal with you,’” Mr. Hardy recalled.

It is one example of a re-emphasis on office staging, also known as a turnkey approach, and it is being propelled somewhat by the new-style millennial office.

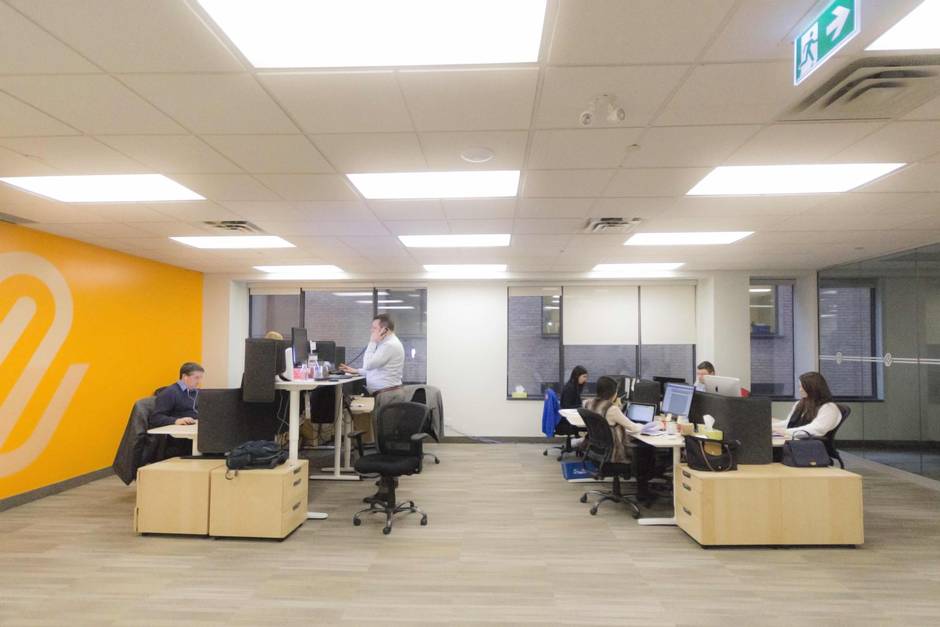

The rationale is simple. To find tenants more quickly and to differentiate one office area from another, landlords are leasing spaces with most of the amenities, such as open work areas, board rooms, collaborative space and kitchenettes, already installed. More than just paint and ceiling tiles, the idea is to spend considerable capital beforehand to upgrade the spaces.

Landlords are using brighter, open-concept designs, and doing this beforehand, so that prospective tenants have to think little about office design and can envision moving in right away.

The other rationale for landlords is that the better the upgrade, the better the potential tenant.

“It is still a pretty competitive market out there,” Mr. Hardy said. “In the sub 5,000 [spaces of 5,000 square feet or less], in my portfolio alone, I probably have 20 or 25 pieces of space like that. And the ability to reduce the downtime or increase the speed that we can get a tenant in there is really, really valuable to us.”

The cost of having an empty office space, known as the carry cost, is about $25 a foot per year for landlords in Toronto, Mr. Hardy said. Even in a seller’s market, such as Toronto’s downtown, which, according to the real-estate services company CBRE has the lowest vacancy rate in North America, there is still the necessity among landlords to fill unoccupied space as quickly as possible.

“A model suite can speed the process significantly for the landlord and the tenant,” said Werner Dietl, executive vice-president, Greater Toronto Area regional managing director at CBRE. “From a tenant’s perspective, they can walk in, and they can quickly visualize what the space will look like. They can quickly outfit it, and it can be up and running potentially in 60 days, versus taking raw space that has been gutted. By the time you have gone through all the permits and the drawings, you’re potentially six months plus.”

This is mostly a strategy for smaller office spaces, as, typically, larger companies will have their specific needs in how staff is organized, how meeting rooms are situated and other ideas of how to organize a floor. Still, Mr. Hardy at Dream noted that this could be done for larger companies taking up full floors, as Dream tries to demonstrate with its own office space.

Built-out small offices are in high demand, particularly in certain sectors, such as technology, and in certain cities. In Montreal, any space less than 3,000 square feet is automatically built-out, said a report by CBRE. And these spaces typically come with shorter leases, catering to firms in flux.

Staging is also being characterized as a move toward more full-service care by landlords, especially for smaller tenants, in terms of walking them through the process and giving them spaces decorated according to different tenants’ tastes.

Among some of Dream’s older office buildings in and around Bay Street, “we have about 15 where a 3,000-square-foot unit could be an entire floor of a building. So, we have smaller floor-plate buildings here where you turn what some people may think of a smaller Class B building into a really cool character space, similar to what the brick-and-beam tenants are getting.” That look can be created in what is actually an office space, he said. “To create your own character and brand in the space, we do that for tenants.”

The less glamorous selling point is also that moving is usually a pain and requires skills that most small businesses don’t possess. This is where the hand-holding especially comes in.

“If you’re a small business looking for a space, you probably don’t have a facilities team that does a lot of the legwork to understand fixturing or the best fit out of a space, and has leverage with general contractors to have the work done quickly,” said Claire McIntyre, vice-president, marketing and communications at Oxford Properties Group’s Toronto office. “With the scale of a large owner, we can do it more easily than a small business can.”

Still, the expense for a landlord is considerable. Even with higher rental fees that landlords tend to charge for the service, anywhere from $4 to $10 extra per square foot, according to the CBRE report, landlords may not recoup the cost over the period of an initial three- to five-year lease. The thinking is that the landlord will make up the expense during subsequent leases for the upgraded property.

The practice is taking place in office districts throughout the country, including weaker markets such as Calgary. As Mr. Dietl of CBRE noted, a lot of Calgary’s downtown office inventory is owned by public companies, backed by large institutional investors. These office owners, who can afford to spend money on upgrades, will be looking to fill vacancies quickly and attract a diverse cross-section of tenants.

In a weakened economy such as Calgary’s, it is also a way to compete with tenants themselves, who may be downsizing and are sub-leasing their own offices to other tenants. With office staging, landlords are “creating direct competition to that,” Mr. Dietl added.

Office staging can be a trickier proposition for private building owners, however. Spending capital on upgrades is a risk.

“For a private owner, it’s a harder value proposition. If you or I owned the building, we’d probably say, ‘No, let’s not spend the money. Let’s wait for the tenants, because I don’t know what’s around the corner tomorrow,’” Mr. Dietl said. “But if it’s a pension fund [which may own a large share of a landlord company], and this is just a piece of their global holdings, this is a long-term strategic decision.”