Everyone knows the definition of a lawsuit: a machine you go into as a pig and come out of as a sausage. A class-action lawsuit, on the other hand, works in reverse: You go in as sausages in a greater cause, and come out, with any luck, made whole pigs again.

Jay Strosberg, the uppity class-action lawyer and partner at Sutts Strosberg LLP who is currently suing Uber (and associated entities) about UberX for $400-million on behalf of beleaguered taxi and limousine operators in Ontario, is himself contemplating a sausage at this moment – the non-metaphorical kind, fashioned from Berkshire pork by Wvrst, a downtown Toronto sausage factory. This is culturally unconventional because Mr. Strosberg is Jewish (his maternal grandfather was an orthodox rabbi) and Wvrst sells non- trayfe sausages as well – even bison, which the Book of Deuteronomy specifically exempts from kosher law. Does Mr. Strosberg order a bison wiener? He does not: He's a class-action lawyer, after all. They like to make their own rules.

Especially when they hail from an underdog town like Windsor, Ont., far from the high-nosed law firms of Toronto. Mr. Strosberg articled on Bay Street, but knew as a new lawyer there he'd never get anywhere near a client. "And they aren't going to let a young lawyer get involved in business development. And I'm pretty good at both." He pauses, contemplates his hot dog, and possibly his inner one as well. "I don't think you necessarily have to practise in a large urban culture to do important work. Windsor's my home. It keeps me humble."

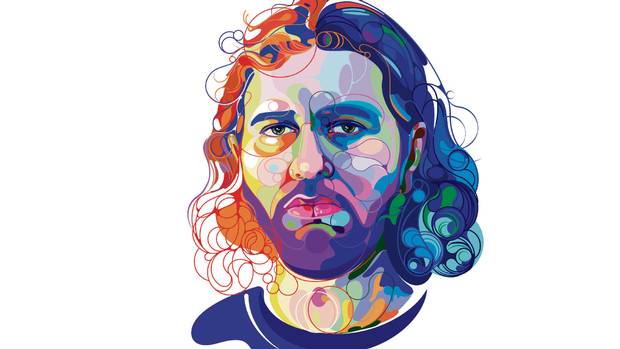

Truth is, Mr. Strosberg is as urbane as any downtown Toronto hipster advocate. At forty, he is sporting pomade and black framed eyeglasses and a slimline navy blue Canali suit and a pink tie, all of which give him the air of a slightly hefty Buddy Holly. (To that effect, he is not eating his hot dog bun, because he's on a strict diet and trying to lose a few pounds – he's down 12 – before the imminent birth of his second child, the first by his second wife, Stephanie, a dental hygienist.) Sutts Strosberg has nice offices in Toronto, too, but Windsor is an easier place to share custody of a five-year-old with his ex-wife Jordana, director of executive communications for Mary Barra, the CEO of General Motors.

Law-wise, Mr. Strosberg is royalty: His father (and partner) is Harvey Strosberg, the former King of Torts who reinvented himself as the founding father of Canadian class-action law when the suits became legal in Ontario in 1993. Father and son have a combative but friendly relationship. (He calls his mother, long divorced from Harvey, every day.) This very morning, Harvey telephoned, unsolicited, to argue a point on one of Jay's cases. Jay responded with unsolicited advice on one of the old man's files – a $3-billion lawsuit in which Harvey is suing the federal government for mismanagement of First Nations' oil reserves. "You don't know anything about the file," Harvey replied.

"Exactly," Jay shot back. There was a time when Jay was seen mostly as the son of Harvey. But Jay now holds his own in a four-person partnership that includes his sister Sharon. (Their other sister, Elaine, is disciplinary counsel at the Law Society of Upper Canada, where her father was once treasurer.) "Class actions are a new business, there's not a lot of law," Harvey says of his boy, "so he can be creative. He has a knack for attracting clients. And he has a good feel for the field. He knows the law very well."

Lexpert recently named Jay Strosberg one of Canada's leading cross-border class-action lawyers, as well as one of its forty top lawyers under the age of forty. "It's all very humbling," Mr. Strosberg says, clearly not that humbled. He estimates his firm has "recovered" more than $2-billion for its clients in the past two decades. "I always like to say, it's a lot of money in Windsor."

Class-action lawyers take 25 to 30 per cent of a gross judgment, if they win. If the Uber case dusts out (optimistically) at $50-million, Mr. Strosberg and his firm will be $12.5-million (plus HST!) richer. But if he loses, they'll make nothing on a case years in the making. Mr. Strosberg guesses that one out of every 200 inquiries he fields results in an actual class-action suit. He was part of the legal team that sued the Atlas Cold Storage income trust for $40-million over an accounting scandal and recently steered a suit against Penn West Petroleum to a settlement of $26.5-million, subject to court approval in Ontario and Alberta.

Class-action law is also nastily competitive. Four years ago, Harvey Strosberg experienced a massive stroke that left him capable of speaking three words, two of which started with the letter f. (One was the name of his stepson.) He has since recovered, learned to speak again, and is practising law vigorously. But with the big guy down, other law firms began to circle.

Sutts Strosberg had filed a $100-million lawsuit against Armtec Infrastructure Inc., after the company suspended quarterly dividends for reasons the Strosbergs thought ought to have been disclosed earlier. Three weeks later, Siskinds LLP, a London, Ont., firm, filed its own suit, challenging Sutts Strosberg's carriage of the suit. Jay fought back and won a $13-million settlement. "I thought it was important to signal to our clients that no one's irreplaceable. These carriage fights can get personal. And I had the distinct impression that it was an opportunistic attempt on their part – that they were trying to kick a guy when he's down." He played basketball and volleyball in public high school in Windsor, though he's only 5'9". "I like to be an outsider," he says.

Securities lawyer Joe Groia – himself no stranger to controversial lawsuits – has known Jay Strosberg for fifteen years. In addition to being more risk tolerant, Mr. Groia says – he devotes half his practice to class actions –"class-action lawyers are more entrepreneurial." They have to see injustice as opportunity, and sometimes opportunity as injustice. Corporations under attack call this cheesy opportunism that creates nuisance lawsuits, but their sputtering outrage is often a front. "They'll never admit this," Mr. Strosberg says of the white shoe firms that defend against class-action suits. "But they love us. The last class-action settlement negotiation I was at, there were 30 lawyers in the room at $15,000 an hour. The worst-kept secret on Bay Street is that class-action defence counsel make more than the plaintiff's lawyers ever do."

Mr. Strosberg's first high-profile case set the pattern for his current endeavours. Back in 2009, he and some pals noticed that Ticketmaster concerts sold out in seconds – but that tickets showed up moments later on Tickets Now, a scalping website, at inflated prices. Mr. Strosberg argued that Ticketmaster and its subsidiary were engaging in an illegal conspiracy: He kicked off a $500-million class-action suit that was in turn instantly championed by U2 and mentioned by The New York Times and CNN. (He's good at the publicity end of his business as well.) As part of the modest $5-million settlement, Ticketmaster shut down Tickets Now. By then Mr. Strosberg had identified a new genre of class action – the kind that springs up at the nexus of the law and new technology.

Hence the Uber suit. Mr. Strosberg admires the ingenuity of using a cellphone as a taxicab dispatching service, which is what Uber does. "But where they cross the line is in asking for unlicensed drivers," Mr. Strosberg says, blowing air between his pursed lips: For reasons unknown to rational man he has ordered grilled jalapenos atop his Berkshire dog. The top of his head is lifting off. He concluded that there were two significant injustices in Uber's business model: It was unfair to licensed cabs and possibly unsafe for the public. At the time the lawsuit was launched on July 23, 2015, in the Ontario Superior Court, UberX drivers didn't have to carry the insurance taxi drivers did, didn't have to use winter tires, and didn't have to submit to driver checks. And because just about anyone can be an Uber driver, a $300,000 taxi medallion in Toronto, now tanks as low as $40,000. Furthermore, "[cab drivers'] revenues are down 40 per cent."

When Mr. Strosberg climbed into a spotless Ambassador cab last spring and was confronted with yet another driver lamenting Uber's unfairness – in five languages to boot – Mr. Strosberg made a proposal. "If you're upset, here's what I do. Why don't we sue them?" The driver said, "I've got nothing to lose." His name was Dominik Konjevic, and he's the point guy in the class-action suit against Uber. (Mr. Strosberg is filing a motion next week to have Coventry Connections, the largest fleet operator in Ontario, added to the suit: The response of the court and Uber will be a good indication of whether the lawsuit has a chance of getting certified and settled.) In the months since, city council has tried unsuccessfully to shut Uber down by injunction, and last month (under pressure from Mayor John Tory) tried to change the rules governing both Uber and taxis – a move that ignited the displeasure of all parties, including the city's licensing and standards committee.

Taxi drivers protesting against Uber in Toronto in December of 2015.

Mark Blinch for The Globe and Mail

Mr. Tory, of course, characterizes the battle as a set-to between forward-looking forces of convenience versus the backward-looking self-interest of the taxi business. Mr. Strosberg – who is more than twenty years Mr. Tory's junior – sees it exactly the other way around. He quickly realized that, despite portraying itself as an upstart, Uber is actually powerful and well-connected – a paid-up member of the business establishment owned by a couple of bazillionaire techheads. Mr. Strosberg immediately cast the taxi drivers as Davids taking on the Goliaths of Uber and City Hall. He was again swamped by CNN and media outlets around the world.

"No other place in the world had convened a class action at the time," Mr. Strosberg points out. He likes to paint a picture of 10,000 to 15,000 UberX drivers, "idling, waiting for a fare. Think about that. The impacts. The environment. The loss of income to the regular taxi drivers. Everything. I think the mayor should be ashamed of himself, frankly. My question to Mr. Tory is, what's really going on here? And I don't think he wants to say."

In other words, it's probably a good thing Mr. Strosberg lives at the other end of the Golden Triangle, in Windsor, and that his political aspirations (he has big ones) are directed toward the Liberal Party, not Mr. Tory's tribe. During the election campaign last year, Mr. Strosberg hosted a fundraiser for Justin Trudeau in Windsor – to the irritation of several well-established Paul Martin cronies. He plans to hold another regardless. He's not a guy who automatically takes no, or religious rules, or the arguments of an opinionated father, or the scorn of a mayor, or traditional loyalties, or social media pressure, or the so-called imperatives of an onrushing future, for an answer.

It all gets back to that pork sausage. He met his new wife Stephanie shortly after he moved out of his former family home and pursued her for two years before she agreed to a date. She's seven years younger than he is. She has since converted to Judaism. "It's more important culturally than religiously," Mr. Strosberg admits, although he has been attending temple more regularly. He's even planning a trip to Israel. "Stephanie's not too happy about that," he admits. "There's safety issues." He pauses. It is the pause of a crusading class-action lawyer. "But there's safety issues here, too. You could be knocked over by an UberX driver."