Mark Charlton, Paul Rutherford, Sammy Sampson and Stéphane Durette, four veterans of Canada's peacekeeping mission to Rwanda in the 1990s, stand outside the peacekeeping monument in Ottawa.Blair Gable/The Globe and Mail

Gloria Galloway reported from Rwanda during the summer of 1994.

There are many things Rwanda veterans say they will never forget about the months they spent in 1994 in a tiny country shattered by genocide.

Corporal Sammy Sampson was part of a four-man team in Gisenyi at the border of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where millions of Rwandan Hutus fled to escape retribution by the rival Tutsis. He watched as Rwandan soldiers burned corpses stacked two-metres high in a mud hut outside the Gisenyi hospital. Afterward, he said, doctors “took us through every ward of the hospital, which turned out to be one of the most traumatic incidents of my life. To see kids maimed, with pieces hacked off of them.”

Pam Rideout, a corporal in the same 1st Canadian Division Headquarters and Signal Regiment as Mr. Sampson, remembers walking up a hill beside her remote communications outpost in central Rwanda and stepping on something with a sickening crunch. “I looked down and my foot was going through the chest cavity of a rotting body.”

Frank Rubia, then a master corporal, remembers the odour that permeated the air: “It was like nothing we’d ever smelled before. It was dirty. It was rotten. That smell will be in my nose for the rest of my life.”

But even if the soldiers can’t forget the horrors they experienced, the federal government doesn’t seem to remember.

Kigali, 1994: Canadian Major-General Roméo Dallaire walks into UN forces' headquarters. Gen. Dallaire appealed in vain for international help with the Rwanda crisis.The Canadian Press

While much has been written about the heroic efforts of then Major-General Roméo Dallaire, the Canadian who led the ill-fated United Nations peacekeeping force beginning in Rwanda in 1993, there is scant record of the second Canadian mission, known as UNAMIR II. The deployment, which helped to bring stability and restored infrastructure to the war-torn country, isn’t recorded on the National Defence Department’s online database, which lists all missions in which Canadians have taken part.

A quarter of a century after they patrolled streets lined with bodies and faced down child soldiers armed with machine guns, under rules of engagement that were unclear, the Canadians who were part of UNAMIR II want the official record updated to show what they accomplished. And the recently established Rwanda Veterans Association of Canada has been advocating for the rights of the injured former soldiers.

Of the 600 Canadian troops who served in Rwanda, half of them – more than double the rate of other recent deployments including Afghanistan, Bosnia, Somalia and Iran – are receiving disability benefits from Veterans Affairs related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“We have been deployed many places in the world and we’ve seen things, but that one [Rwanda] was just totally out of this world,” said Denis Lebrun, who was the regimental sergeant major for the signals regiment. “It was not a mission, it was a nightmare.”

Nov. 24, 2018: Retired soldier Sammy Sampson walks with the children of Rwanda genocide survivors to a ceremony in Manotick, a southern suburb of Ottawa. The event honoured Rosamond Carr, an American humanitarian who founded an orphanage in Rwanda and became an ally of Mr. Sampson and his comrades. She died in 2006.Blair Gable/The Globe and Mail

Mr. Sampson tosses a rose into the river. He was a corporal during the Rwandan genocide in 1994, and has worked to reconnect his comrades from the mission.Blair Gable/The Globe and Mail

Mr. Sampson listens to a genocide survivor speak at the Manotick ceremony. 'There was something different about Rwanda, we were just traumatized so much,' Mr. Sampson recalls of the conflict. 'Young soldiers that had bright careers in front of them were being forcibly retired because of this.'Blair Gable/The Globe and Mail

The mission

When prime minister Jean Chrétien’s cabinet was considering deploying troops to Rwanda in the spring of 1994, the genocide that had seen the massacre of more than 800,000 people was in its last throes. The civil war, however, was still raging.

The federal ministers would ultimately agree to send Canadian forces on three conditions: That the UN objectives were achievable; that Canada’s role was clear and the risk acceptable; and that the other members of UNAMIR II – mostly members of the African Union – would arrive in a timely manner.

But cabinet documents from the day, obtained through the Access to Information Act by Mr. Sampson, who founded the association for Rwandan veterans, make it clear that federal ministers were concerned both about the safety of the troops and the evolving combat situation on the ground.

When the main contingent of Canadians did land in Kigali in late July, 1994, a ceasefire had been declared between the Tutsi-backed Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and the remnants of the Hutu-Rwandan government forces who had led the slaughter. But pockets of fighting remained.

0

65

MAP KEY

KM

Canadian, UN HQ

UGANDA

Canadian team

Major massacre site

Genocide perpetrators

TANZ.

Byumba

Gisenyi

RWANDA

Lake

Kivu

Kigali

Gitarama

Kibuye

Kibungo

Cyangugu

Gikongoro

Butare

AFRICA

DEMOCRATIC

REPUBLIC

OF THE CONGO

DETAIL

BURUNDI

john sopinski/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP; Sammy Sampson

0

65

MAP KEY

KM

Canadian, UN HQ

UGANDA

Canadian team

Major massacre site

Genocide perpetrators

TANZ.

Byumba

Gisenyi

RWANDA

Lake

Kivu

Kigali

Gitarama

Kibuye

Kibungo

Cyangugu

Gikongoro

Butare

AFRICA

DEMOCRATIC

REPUBLIC

OF THE CONGO

DETAIL

BURUNDI

john sopinski/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP; Sammy Sampson

0

65

UGANDA

KM

AFRICA

Bukoba

DETAIL

Byumba

Lake

Victoria

Gisenyi

RWANDA

TANZANIA

Lake

Kivu

Kigali

Gitarama

Kibuye

Kibungo

Cyangugu

Gikongoro

Butare

MAP KEY

Canadian, UN HQ

Canadian team

DEMOCRATIC

REPUBLIC

OF THE CONGO

Major massacre site

Genocide perpetrators

BURUNDI

john sopinski/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP; Sammy Sampson

Kigali, June, 1994: Gen. Dallaire and other Canadian officers visit the refugees in Amahoro soccer stadium.Corinne Dufka

The Canadians' first order of business was to clear out Kigali’s soccer stadium so it could be used as a barracks. It had held large numbers of Rwandans during the months of the killing and was the site of shallow mass graves.

Richard Davey, a master corporal with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, said it was his task to make the stadium safe. Dogs abandoned during the genocide had developed a taste for human flesh. “So I sat up in the bleachers, shooting wild dogs, and that was our first engagement."

General Paul Rutherford, who was then a major, said Maj.-Gen. Dallaire deemed the original deployment schedule – which would see members of the Armed Forces sent gradually to bases according to the “operational readiness” of the arriving units – to be insufficiently urgent. Maj.-Gen. Dallaire wanted communications established throughout Rwanda as soon as possible. And the Canadians complied.

Gen. Paul Rutherford, shown at the November veterans' event in Manotick.Blair Gable/The Globe and Mail

A UN document dated July 19, 1994, confirms that many areas of Rwanda remained “very volatile and are not safe for immediate deployment.” Nonetheless, four-person detachments of signals-regiment soldiers were sent into the regions with portable radios, guns and not much else.

“There were quite a few instances where we were held up at gunpoint and we didn’t know which way it was going to go,” said Al Lopes, the radio troop’s warrant officer.

Compounding the horror was the feeling, on the part of the Canadians, that they were helpless to save large numbers of people, either because of their small numbers, their lack of resources or their uncertain rules of engagement.

The UN categorizes missions according to the force that troops may use during their deployment. A Chapter VII mission allows them to take military action to restore peace and stability. They can engage the enemy. A Chapter VI mission allows for the peaceful resolution of disputes. Soldiers may fire their weapons only in self-defence.

UNAMIR II was authorized as Chapter VI, but a memo obtained online by Mr. Sampson quotes a senior Defence official as saying the mission should be regarded as a “Chapter 6½,” a designation that doesn’t even exist.

When Mr. Sampson first saw the document, he said, a light turned on for him. “It explained how the government managed to get a peacekeeping force into a situation that required more force than self-defence. You create a new chapter.”

Al Lopes sits in the crew commander's hatch of a Grizzly AVGP with gunner Cpl. Christopher Parsons behind him.

UN troops from other countries took months to arrive and, in many circumstances, the Canadians were left entirely on their own.

Mr. Lopes recalls driving with a contingent of Canadian troops through a village an hour outside of Kigali and seeing a man lying on the ground shielding his face from the blows of other Rwandans who were attacking him with sticks. Mr. Lopes called into UN headquarters, asking that he and his men be allowed to intervene. But they were told to stay out of it.

“A few days later when we came back through the same village, I happened to look over to where that guy was being beaten and all that was left of him was char,” said Mr. Lopes, who was responsible for all of the soldiers in the detachments outside Kigali. “They killed him and burned him. He still had his hands up in front of his face.”

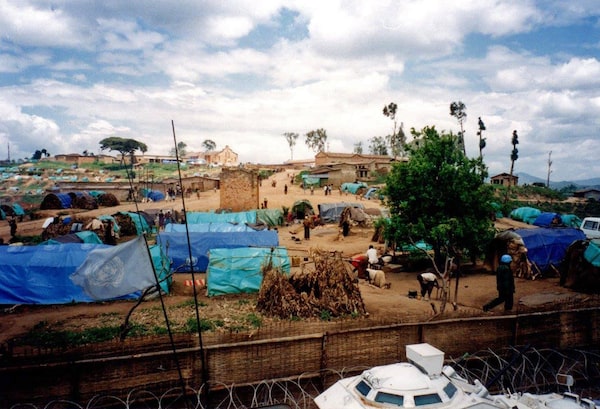

A view of Kibeho refugee camp, as seen from one of the Grizzly AVGPs that formed part of the UN's communications command post.

Still, in the face of adversity, the Canadians did the job they were sent to do.

Everywhere the soldiers went in those early days, children were begging for food and water.

Mr. Lopes said his soldiers routinely gave away their rations. "When we got there, people were starving,” he said. “Guys would just rather go without eating and would give their food to the kids.”

Thousands of children were walking the streets alone after their parents had been killed in the genocide. So the Canadian soldiers created orphanages, and brought provisions to those built by others.

Under the constant threat of attack from insurgents, Canadians established a key radio rebroadcast station at the top of Mount Karongi, one of the highest places in the mountainous country. Very soon into the mission, it was allowing people across Rwanda to talk to each other for the very first time.

Members of the signals regiment ferried displaced people – mostly women, children and the elderly – from danger zones in the west to the protection of the east, passing through repeated checkpoints where armed members of the RPF would try to take the displaced people off the trucks.

Army engineers, who worked mostly with hand-held tools because their power tools were on later flights, made significant strides to restore basic infrastructure such as plumbing, and to create security posts.

The Canadians “were clearing bodies out of places and doing all kinds of things to improve the conditions,” Mr. Dallaire said. “A lot of those guys got deployed into some pretty isolated places and lived in that isolation for a long time. They were nothing less than a godsend."

Kigali, 1995: A child looks out from under a banner memorializing the Rwandan genocide's victims at a cemetery where thousands of victims were buried.Ricardo Mazalan/The Associated Press

How it was forgotten

The Canadian mission lasted six months. In early 1995, the troops began returning home, a few at a time.

Mr. Sampson, the corporal who was sent to Gisenyi, said he wondered, as he flew into this country’s airspace, how he would explain what he and the others had gone through and what they had witnessed. He decided “it was not a story we could tell.”

His plane landed in darkness, and he was sent quietly back to his base. There were no media reports to announce that the deployment had ended.

By April, he and the other troops started getting new posts and life was seemingly returning to normal. But nothing was normal any more, Mr. Sampson said.

The military had yet to accept that PTSD was a real thing, and anyone who admitted the mental difficulties they were experiencing as a result of Rwanda would have been branded a weakling or a coward, he said. So no one talked.

Most of the troops were veterans of previous missions, “but there was something different about Rwanda, we were just traumatized so much,” Mr. Sampson said. “People were just falling off, people were just starting to disappear. People were losing it. Young soldiers that had bright careers in front of them were being forcibly retired because of this.”

And, over the years, when soldiers spoke up about what they saw – the bodies being dumped into pits with bulldozers, the Rwandans dying in their arms, the little children with their limbs hacked off, the things that were accomplished – they were branded liars, even by other veterans who did not go to Rwanda, Mr. Sampson said. “Because they have no history” on official sites.

Rwanda, 1994: Two Canadian soldiers from the signal regiment take part in a raid of Rwandan refugee camps in search of weapons and agitators.Stephane Grenier/The Canadian Press

Today, Veterans Affairs Canada’s website pays tribute to Mr. Dallaire and two other officers, and talks about the chaos and the dangers in Rwanda, and the psychological damage inflicted on the soldiers sent there. But it makes no mention of UNAMIR II and what the Canadian soldiers achieved.

As for the Department of National Defence, it does little to acknowledge that the mission even took place.

Department officials said in an e-mail that, although the mandate in Rwanda changed several times over the course of the operation, there was only one mission name, and that was UNAMIR – some aspects of which, they said, have yet to be added to the department’s database 25 years later.

But there was a separate UN Security Council resolution on June 8, 1994, extending the mandate and authorizing additional battalions of soldiers. And in correspondence from various government and UN sources, the UN and Canadian government clearly state that they are participating in UNAMIR II.

Even the Canadian Encyclopedia misstates that the troops were deployed in 1993, before the genocide broke out.

All of which compounds the psychological problems of the Rwanda vets. “When veterans have trouble convincing their psychologists that what they are saying about Rwanda is true, and family members receive conflicting stories from their government, how is a soldier supposed to move on with their injuries?” Mr. Sampson said.

Rick Cameron, a former sergeant, said each of the seven men who served at his outpost now struggles with PTSD and other mental issues. “I am pretty sure most of us think about it 24/7,” he said.

Mr. Davey, the master corporal who was shooting the dogs, said he came back from Rwanda a changed person, who ended up losing his marriage and his relationship with his son as a result of his psychological state.

Ms. Rideout, the corporal who stepped on a rotting body, said she developed symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as hypervigilance, and has nightmares about machetes. She was diagnosed with PTSD in 1999.

And, although they were given medals, they are the medals of the failed UNAMIR mission.

The Defence Department maintains that it is up to the UN to decide whether a distinct medal should be given for any particular mission. Yet in Australia, the governor-general upgraded the medals for that country’s troops who went to Rwanda to show that they took part in a separate mission, and to acknowledge the brutal, “warlike” conditions that they faced.

Mr. Rutherford said the Canadians who were sent to Rwanda in 1994 accomplished their objectives, and much more. “They did phenomenal work, they really did,” he said, pausing to gain control of his emotions. “I will be proud of them, always, always, always.”

Mr. Sampson said the soldiers he keeps in touch with who went to Rwanda would do it again. But they want the history corrected on government websites and elsewhere so their children will know what they accomplished. They want Canadians to know the horrors they endured and the toll the mission has taken. And, said Mr. Sampson, they would like to return to Rwanda as a group, to see the country as it is today – a trip they believe would play a healing role in their recovery.

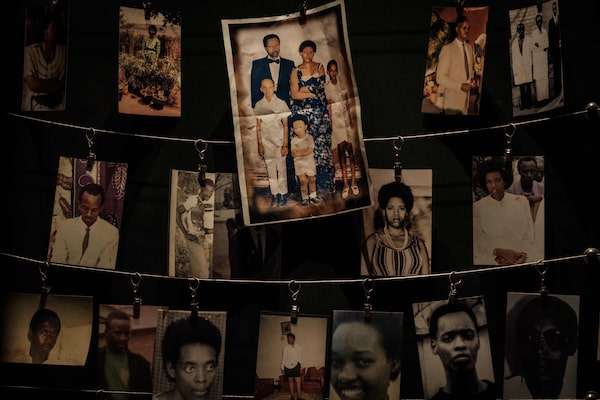

Kigali, 2018: An exhibition at the Kigali Genocide Memorial shows portraits of genocide victims. Bodies from the genocide era are still being found across the country.YASUYOSHI CHIBA/Getty Images

The memorial's remembrance flame blazes under a full moon.YASUYOSHI CHIBA/Getty Images

Under President Paul Kagame, shown in 2019, Rwanda is now considered one of the most peaceful countries in Africa.ARND WIEGMANN/Reuters

Rwanda now

For the past 19 years, Rwanda has been headed by President Paul Kagame, who some allege had a hand in the assassination of a predecessor, the catalyst for the genocide. Human-rights organizations have cast doubt on the legitimacy of recent elections that brought him to power. Nonetheless, Rwanda is considered one of the most peaceful and progressive countries in Africa.

A system of community justice and an international tribunal spanning many years instilled a cautious sense of reconciliation among citizens. Now, the country of nearly 12 million is a tourist destination and one of the fastest-growing economies on the continent.

It is the Rwandans who ultimately brought a halt to the horrors and turned the course of their country. But the Canadian soldiers helped the Rwandans on their road to stability.

“By the time I left on the 19th of August [1994], it was day and night,” Mr. Dallaire said.

In 1994, Adrien Niyobuhungiro was four years old. He and his family fled to Gisenyi and then to the DRC during the genocide. His father, who helped to construct orphanages and other buildings, would walk to his jobs with the Canadian soldiers to stay safe. “In their presence, no one would attack you,” said Mr. Niyobuhungiro, who spoke on the phone from Rwanda. After the Canadians left, his father was killed by machete in front of him and his mother died from the resulting shock.

Gilbert Munyampeta, who now lives in Gatineau, was five years old and living in an orphanage near Gisenyi in western Rwanda when he first encountered the Canadians. He said he remembers the troops well. They brought beds and blankets. And sometimes they would bring food. “They protected us,” Mr. Munyampeta said. "They gave us hope for life.”

Blair Gable/The Globe and Mail