The sharp end of global geopolitics used to be a comfortable distance away. Now it is getting closer to Canada.

It’s not just that the Northwest Passage is melting and China is eyeing it as a shipping route. Or that Beijing bars Canadian canola or meat when it is upset and throws Canadians in jail when it is angry. Or that agents of India allegedly plotted to kill a Canadian citizen in Surrey, B.C., and New Delhi bristled dismissively when Canada complained.

It’s that all those things have been happening at a time of power shifts that have shaken the sense that there are global rules – and left Canada more vulnerable.

Yet Canada doesn’t have a foreign policy for this changed world. The body politic remains in a bubble of the world it has known for decades, securely surrounded by three oceans and a superpower, satisfied it is in a club of Western allies that sets the rules of the world order, and comfortable enough to tout its values to the world without worrying about protecting its interests.

There is no escaping the ripples of conflict at a time when the Israel-Hamas war has created global tensions and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has frightened Europe. The U.S. is strained by both and riven by domestic politics. There is a new era of superpower competition with a rising and coercive China.

And there are more powers with more tools to reach around the world, countries that don’t feel as bound by old genteel rules and are willing to pick a fight with Canada. Saudi Arabia, for example, froze investment over a tweet.

A Japanese soldier takes part in a marine landing drill on Tokunoshima island. Japan's military budget is set to rise dramatically.Issei Kato/Reuters

Some are rewiring for a tougher world. Japan, a country with a constitutionally quasi-pacifist policy since 1947, is in the process of doubling its military spending over the next five years. Germany rearranged the nation’s energy supply to break its dependence on natural gas piped from Russia.

Canadians, however, haven’t felt foreign policy is critical to their security or their prosperity. That has fed a generation of benign neglect.

Familiar relationships in Washington and Europe came first, so Canada didn’t diligently build influence in the fast-growing economies of Asia. Diaspora politics sometimes displaced calculations of the national interest. Governments let the military decline and failed to develop national-security policing and intelligence to meet new threats. All while Canadians ascribed to the conceit that the world needs more Canada.

“We have coasted for years,” Ward Elcock, a former director of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and former deputy minister of national defence, said in an interview. “Is it just the politicians, or is it Canadians? Canadians feel safe.”

John McKay, chair of the House defence committee, worries about 'creeping marginalization' for Canada in world affairs.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

As a political commodity, foreign policy writ large is in low demand. Liberal MP John McKay, the chair of the Commons defence committee, has come to believe that successive Conservative and Liberal governments kept military funding low because voters don’t ask for it.

“I cannot think of a conversation at the door in the last two or three elections where anyone has been concerned about the inadequacy of our support for the military,” he said. Conservative opponents? “They’re knocking on the same doors.”

The effects accumulate. “The chronic underfunding of defence, diplomacy, development – and parliamentary diplomacy – has resulted in creeping marginalization. Of us. Of Canada,” Mr. McKay said.

As global risks rose, Justin Trudeau’s government redrafted foreign-policy rhetoric. In a 2017 speech, then-foreign affairs minister Chrystia Freeland focused on protecting the rules-based international order. In October, Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly recognized that order has eroded in a major speech and promised a newly pragmatic foreign policy based on defending Canada’s sovereignty and building ties with a broader set of partners.

But look at the Indo-Pacific strategy Ms. Joly outlined last year, belatedly, to chart a serious course in a massive, dynamic region while keeping a wary eye on a disruptive China: It leaned heavily on expanding ties in India, and that is now in tatters. The strategy called for augmenting Canada’s naval presence, but that only meant sending a third frigate into two vast oceans, for part of each year.

Canada hasn’t kept up with a world that changed. And here we are now: Multilateralists who lost two United Nations Security Council elections, free-traders subjected to coercive trade bans, and old allies left out of new security groups.

In the day-after frenzy of his 2015 election victory, Mr. Trudeau delighted Liberals at a victory rally with a simple message to the world: “We’re back.”

“I think that there was a sense at the time that the world was changing quickly,” said University of Ottawa professor Roland Paris, who was a foreign-policy adviser to Mr. Trudeau during his first months in power. “In hindsight, it’s jaw-dropping how fast some of those changes have been.”

Russia was expelled from the G8 for invading Crimea in 2014; now, there is a full-scale war in Europe. There is an overt superpower rivalry: In October, while U.S. President Joe Biden dispatched fleets to monitor the Mideast war, China’s Xi Jinping hosted 20 leaders, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, to talk about a new world order. Rising swing-nations are flexing power, and foreign interference comes in myriad forms, from social media to foreign police stations.

Mr. Trudeau’s first month in office was marked by a dash through four global summits, and being mobbed by selfie-seekers in Manila. But the Canada he thought would be welcomed back is more alone than before.

His first term was dominated by the danger of Donald Trump’s threat to withdraw from the North American free-trade agreement and bring in a tariff wall on Canadian exports. Mr. Trudeau’s all-points lobby to win allies inside the U.S. and eke out a draw was his most notable international success.

But Mr. Trump’s tenure also amounted to a warning that the U.S. relationship is more fragile than Canadians assumed. Many Americans don’t see Canada as part of a North American bloc or an indispensable partner.

President Xi Jinping gestures to Mr. Trudeau at their meeting in Beijing in August, 2016.Wu Hong/Reuters

In 2016, Mr. Trudeau travelled to China with gifts for Mr. Jinping – medallions bearing the image of Norman Bethune struck for his father Pierre’s visit to China in 1973 – courting a stable relationship and mooting a possible free-trade deal.

That appears misguided now, but Australia, often cited as an example of middle-power realpolitik with China, had signed a free-trade agreement with Beijing the year before. It was the late days of Western hopes that trade engagement with China would make Beijing a more constructive global player. Win-win.

Now the promise of win-win has deflated. It popped for Mr. Trudeau in 2018, when Beijing retaliated for Canada’s arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou by arresting Canadians Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig. Then Beijing cut off canola imports from Canada. And froze meat imports.

China’s big economy gives it leverage, which it uses in geopolitical disputes, from banning Norwegian salmon when dissident Liu Xiaobo won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 to responding to Australia’s call for a COVID-19 inquiry by levying tariffs on Australian barley, beef, cotton and wine – despite the free-trade agreement.

Other countries learned the lesson: Deeper ties, including trade, can be used for coercion, a dynamic dubbed “weaponized interdependence” by American political scientists Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman.

Riyadh's reaction was swift when Chrystia Freeland, then the foreign affairs minister, tweeted about the plight of Saudi blogger Raif Badawi and his sister Samar.CP, Reuters, X (formerly Twitter)/The Canadian Press, Reuters, X (formerly Twitter)

Ms. Freeland’s 2018 tweet calling for the release of jailed Saudi dissidents, and another from her department in Arabic, led Saudi Arabia to freeze investment, obstruct trade and recall Saudi students. India’s response to Mr. Trudeau’s assassination allegation didn’t just force out 41 Canadian diplomats, but suspended visa processing to upset the Indo-Canadian community. The dispute actually bolstered the popularity of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party.

Those are not uniquely Canadian experiences. Türkiye accused Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of ordering the assassination in Istanbul of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018. Germany complained Türkiye intimidated Turkish-Germans during election campaigns.

The idea that India, a democracy even if Mr. Modi’s government has eroded its protections, would plot to assassinate Canadian and U.S. citizens – if true – shows it is testing the reach of its new global power. So does its response to each accuser. Mr. Modi dismissed Mr. Trudeau’s calls to co-operate in an investigation. But India responded to allegations of related assassination plots revealed later in a U.S. federal indictment by convening a committee of inquiry.

The U.S. was already pressing its complaints with India behind-the-scenes when Mr. Trudeau made his shocking allegation on Sept. 18 – but Washington, and other close allies, responded by expressing concern, not condemning India. The U.S., after all, is courting India – which has skirmishes with China but buys oil from sanctioned Russia – as a partner in its rivalry with China.

“The Americans aren’t going to manage our relations with India for us,” said Carleton University professor Fen Hampson, the author of several books on foreign policy.

“We have to handle our own interests in those things. They’re not easy to handle, because you can’t stop every assassination. So you need to have other ways of building up your influence and your strength.”

What should Canada do?

“I would say there needs to be a really fundamental mindset shift,” argues Amrita Narlikar, the Hamburg-based president of the German Institute for Global and Area Studies.

Hard power such as military capability is important and will become more so with geo-economic shifts, she said. But it takes time to build, and other steps are important.

Trade is no longer just trade in the age of weaponized interdependence, so countries should try to increase economic security, including realigning global supply chains to ensure that strategically important sectors, such as high-tech, pharmaceuticals and key minerals, depend on trusted partners, she said. Canada would still have transactional relationships with some countries, but its interests require building closer political relationships beyond its old allies.

Prof. Narlikar argues that Canada still approaches the broader world by trying to fit potential partners in Asia, Africa and Latin America into the same paradigm as its European allies, with even its oft-repeated commitment to multilateralism looking like Western-rules “old-world multilateralism.”

She compared Canada’s approach with that of the circle of European trade officials who have stuck with the same narrow, technocratic approach over years of failed global talks, which she has criticized as the “Brussels bubble.”

“I think there is a Canada bubble,” she said.

A key first step is to recognize that the Global South – the many post-colonial and developing countries who felt left out of the power structures of the postwar order – matters. A second step, she said, is to differentiate among them, separating out countries Canada cannot consider a partner but expanding its conception of those with “like-minded” values with whom it can build trust.

As an example of missed opportunities, Prof. Narlikar points to the influential BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. The members have serious differences but still meet regularly and now, new members – Saudi Arabia, Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates – are joining. Western countries such as Canada should seek to build ties with some, she said, cultivating a deeper understanding of their politics, and avoid pushing countries such as Brazil or India into the same corner as countries with very different values such as Saudi Arabia.

“We in the West need to know what our red lines are,” Prof. Narlikar said. “But there needs to be a recognition that there are other countries that are also democracies.”

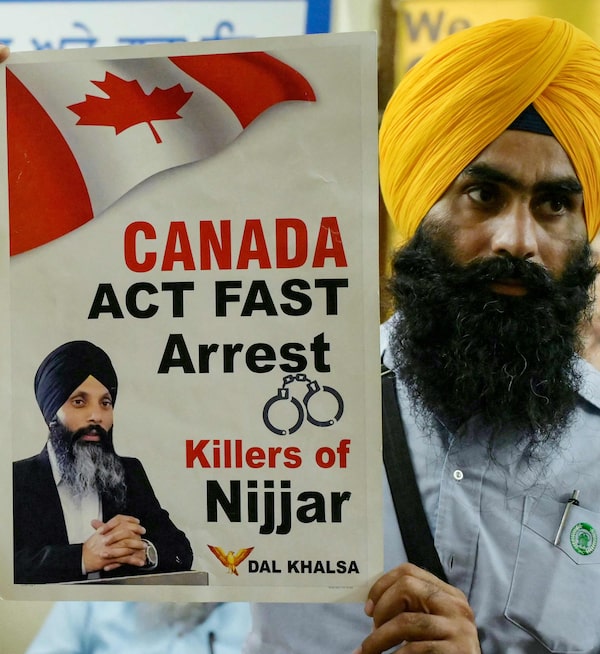

A member of a Sikh group in Amritsar calls for action in the investigation of Hardeep Singh Nijjar's death.NARINDER NANU/AFP via Getty Images

Mr. Nijjar's friend Gurpatwant Singh Pannun was also the target of an assassination plot that was never carried out, U.S. officials said.Ted Shaffrey/The Associated Press

Drawing those red lines isn’t always clear. Right now, India looks like a case in point.

The allegation that agents of New Delhi were involved in the shooting death of Sikh activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar, now echoed in a U.S. federal indictment, has made deterring Indian interference in Canada – and protecting Canadian Sikhs – a national-security priority.

The U.S., however, has responded very differently to an alleged plot to kill U.S. and Canadian citizen Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, signalling it does not want the case to derail its strategically important relationship with India.

Canada-India relations have been marked by suspicions over diaspora politics for decades, with India accusing Canada of being soft on separatist extremists in the Sikh-Canadian community since the 1985 bombing of Air India Flight 182, which killed 329, including 268 Canadians.

The movement to carve a separate Khalistan from northern India is now marginal in India, but New Delhi still complains that the energetic, pro-Khalistan activism in Canada is a foreign-based threat – though former Canadian intelligence officials insist they did not find violations of Canadian law. Canadian officials told Indian counterparts that support for separatism is a matter of free speech.

Mr. Modi’s government has now accused Mr. Trudeau of being motivated by politics – presumably pro-Khalistan Liberals. Omer Aziz, who worked as a foreign policy adviser in the Liberal government in 2017, said the government was certainly concerned about support from Sikh Canadians, and could have conducted more diplomacy.

“There was a major disconnect. Just saying it’s a free-speech issue and we can’t really address it,” Mr. Aziz said. “We could have assuaged their concerns somewhat.”

Montrealers take part in a pro-Israel rally on Oct. 10, days after the Hamas attacks.Christinne Muschi/The Canadian Press

Canada is far from alone in having to negotiate the impact of diaspora politics on its foreign relations. The opposing, vociferous demonstrations over the Israel-Hamas war illustrate that governments can face intense domestic pressure about overseas events. Mr. Trudeau’s government’s initial stand-by-Israel rhetoric after Oct. 7 has shifted to calls for a ceasefire, dividing his own caucus of MPs.

And there is a long history of politicians using stands on issues abroad to win votes in communities or compete for parts of them.

“The foreign policy of this government, and it is not unique to this government, is very much driven by identity politics,” Prof. Hampson said.

The federal government promotes a feminist foreign policy that appeals to women voters, he said, and successive governments have used foreign statements to appeal to Ukrainian-Canadians or Tamil-Canadians. In a democracy, the views of communities will be considered, Prof. Hampson said, but they can predominate if there is a weak sense of national interests.

“The bigger question,” said Prof. Paris, “is how important are we as a country?

“How much importance are we as a country, and our governments, going to place on foreign policy? Because the more foreign policy is recognized as critical to Canada’s future prosperity and security, the more Canadian interests are going to drive our foreign policy across the board.”

Jean Chrétien, then Canada's prime minister, serves fries at a Canadian fast-food outlet in Beijing in 1998.Fred Chartrand/The Canadian Press

In Canada, however, defining interests has not always been seen as a necessity.

In 1995, Jean Chrétien’s Liberal government issued a foreign-policy white paper that reported the Cold War had ended, replaced by an era of multilateral co-operation. It listed promoting Canadian values and culture as a key goal.

When bureaucrats were asked to update it five years later, they decided to state the obvious: that the U.S. was key. “We would bring that front-and-centre and admit that this was our key relationship,” said Randolph Mank, then-director of policy at the Foreign Affairs department. His team proposed measures to secure the border and keep goods and people flowing.

Political strategists and then-foreign affairs minister John Manley were not enthused. It wasn’t what Canadians wanted to hear about their role in the world. Then Sept. 11 happened. Keeping borders open became the national priority. Mr. Manley became border czar. Canada’s interests were made clear.

A generation later, a changing world is pressing Canada to put the recalculation of its interests ahead of the tales it tells itself about its role in the world: among them, the notion that “the world needs more Canada” and the implication that foreign countries are waiting to hear Canada’s views.

There is arguably a consensus now that the U.S. economic relationship is crucial, but it has been clear for decades that diversifying, notably with Asia, is in the national interest. Canadian sovereignty requires defences against foreign interference and resilience against coercion. Advancing Canada’s interests involves building influence with allies and other partners, with diplomacy and hard power.

In October’s speech, Ms. Joly addressed many of these issues, promising more tools of power in the military, intelligence and cybersecurity. She said she’d make relationships with Japan and South Korea as close as those with Britain and France, and “invest” in the ASEAN nations of Southeast Asia as Canada has in Europe.

But in reality, that speech was an assertion of what Canada should do – if it had the will.

For two decades, successive Canadian governments promised deeper efforts to engage the ASEAN nations but failed to follow up. To his credit, Mr. Trudeau has re-engaged, attending ASEAN summits in 2022 and 2023 and launching free-trade talks. That is welcome, but overdue, said one senior ASEAN country official. Canada has yet to embrace the mindset of a Pacific country, he said.

Mr. Trudeau and son Xavier chat at this past September's ASEAN summit with Indonesian President Joko Widodo and his wife Iriana.MAST IRHAM/Pool via REUTERS

Across the Indo-Pacific, maritime security is a key concern that brought together Japan, India, Australia and the U.S. in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. Canada was not asked to join. Why not?

“That’s a realistic appraisal that there’s not much in the way of military assets that we can bring to that particular conversation,” said Mr. McKay, the Liberal MP.

What matters is not just being left out of a group, but that Canada is not seen as a useful security partner in the Pacific. The U.S. asked Canada to lead a mission to Haiti, which Mr. Trudeau declined – but the Prime Minister really didn’t have a choice because the Canadian Armed Forces could not mount a force. European allies, concerned by Russian aggression, are happy Canada sent troops to Latvia, but the Forces are struggling to meet a commitment to build up a NATO brigade.

Mr. Trudeau came under fire in April when a leaked U.S. document revealed he had privately told NATO allies Canada would never meet the alliance’s target of spending two per cent of GDP on defence. But that was political realism: Canada hasn’t hit that level since 1987. In fact, Mr. Trudeau’s government has increased military spending slightly compared with that of his Conservative predecessor, Stephen Harper, who raised spending during the Canadian mission in Kandahar and then let it drop.

Capacity has declined. Major weapons systems such as frigates and fighter jets date from the 1980s and 90s and are still to be replaced, with smaller fleets. General Wayne Eyre, Chief of the Defence Staff, has warned the understaffed Forces can’t meet its mandate. In November, Vice-Admiral Angus Topshee said in a video that the Royal Canadian Navy he leads is in a “critical state.”

Canadian soldiers must often make do with limited staff and aging vehicles.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

Canada won’t be a major military power, to be sure, but its influence with increasingly stretched allies will be linked to how useful it is in security matters. A Canadian military presence would lend weight with other partners in regions such as the Indo-Pacific. At home, the fact that the U.S. sees protecting Canada’s North as part of its own security has afforded this country protection, but there is still a potential risk to its sovereignty. A lack of participation in North American defence might one day lead an indebted, America-first U.S. to cut Canada out of joint defence decisions.

Global security and protecting sovereignty require the increasingly vital domestic tools of foreign policy in an era of widening foreign interference. Beijing’s efforts to meddle in Canadian politics or press Chinese Canadians make a compelling case for an upgrade of intelligence and legal tools such as a foreign-agent registry. The fact that the U.S. foiled an alleged Indian assassination plot and Canada did not adds to the ample evidence that national-security policing is inadequate.

Those are not quick-fix adjustments. If relations with India are frozen, Canada can redouble efforts with other Asian countries. Resilience requires building stronger ties outside Canada’s habitual circle, greater self-reliance, influence with allies, hard power and security.

They are also not the things Canadians have wanted to hear about their role in the world. But the series of little shocks of geopolitics reaching into this country are now a feature of the planet, and they are likely to get bigger. That requires a recalculation of interests in the world, and a recognition that foreign policy is critical to Canadians, even at home.

Foreign affairs: More from The Globe and Mail

As Israeli and Hamas forces fight in Gaza, the tiny Persian Gulf state of Qatar is playing a big role in negotiations behind the scenes. Kristian Coates Ulrichsen from Rice University spoke with The Decibel about how they became the go-to mediator for a polarizing conflict. Subscribe for more episodes.

Israel-Hamas war

Canada’s ceasefire call ‘naive,’ has no impact on war, Israeli envoy says

Canada should halt weapons to Israel, arms control advocate says

How the Israel-Hamas war is dividing the United States

War in Ukraine

Putin eyes more Ukrainian territory, sending aggressive message at press conference

Ukrainian government shifts blame to foreign media as dissent grows