How can Canada make its democracy safer from malicious meddling from abroad? The Foreign Interference Commission hopes to answer that, and after months of quiet work behind the scenes, its public sessions are back in business as of Sept. 16. Justice Marie-Josée Hogue’s final findings, due by the end of the year, will give Parliament – which is potentially headed for a new election sooner than expected – ideas for new measures beyond the ones enacted this summer.

In Phase 1, Justice Marie-Josée Hogue heard from parliamentarians, the Prime Minister’s aides, Canada’s spy chief and other officials about how rival states tried (and, in the judge’s view, failed) to skew the overall outcome of the last two federal contests. Now, she looks to a broader timeframe and bigger questions about who is responsible for deterring interference in the future.

Here’s a primer on what’s happened so far.

Justice Marie-Josée Hogue is a Quebec appeal-court judge who now leads the Foreign Interference Commission.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

Why are we having a foreign-interference inquiry again?

Canada’s ties with China, Russia, India and Iran have been more frayed than usual in recent years, each for different reasons, so those countries and others have motive to meddle in our domestic politics to reward candidates they like and hurt the ones they don’t. The Canadian Security and Intelligence Service found worrying examples of misinformation and voter suppression in 2019 and 2021, mostly aimed at opposition MPs critical of Beijing, such as Conservatives Michael Chong, Erin O’Toole and Kenny Chiu and New Democrat Jenny Kwan. Justice Hogue’s commission has also looked into whether Moscow, New Delhi or Tehran tried something similar.

As The Globe and other news outlets reported the allegations against China last year, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau chose former governor-general David Johnston to look into them. His confidential report advised against airing CSIS’s findings at a public inquiry, “given the sensitivity of the intelligence.” Pressed for a more open accounting of the facts, Mr. Trudeau launched an inquiry after all, the one Justice Hogue is leading.

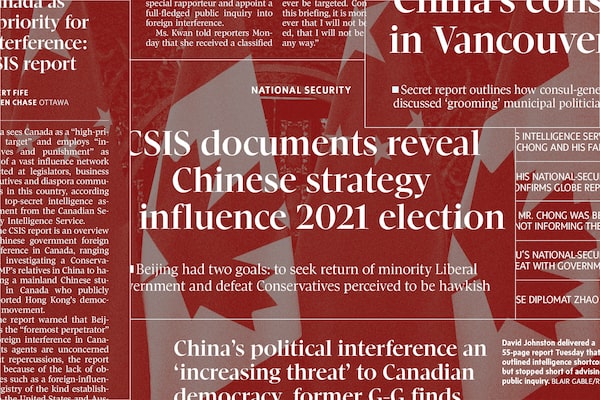

Illustration by The Globe and Mail (source: Fred Dufour/CP, AP, The Globe and Mail)

What happened in Phase 1?

Phase 1, whose hearings spanned January to April, was more of a fact-finding mission to see whether foreign actors had skewed the outcome of elections or local nomination races, and if so, when CSIS told politicians what had happened.

Justice Hogue heard from MPs and diaspora groups who were allegedly targeted, and from other politicians accused of being too close to China, who sought to clear their names. Many of the witnesses testified in camera to protect classified evidence, but the public hearings – and May 3′s initial report from Justice Hogue – offered Canadians at least some conflicting insights into who knew what, and when.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau testified to the commission on April 10, in the final week of the first phase of hearings.ASHLEY FRASER/AFP via Getty Images

‘Bragging is not doing’: Trudeau, the PMO and what CSIS told them

Justin Trudeau’s staff and CSIS director David Vigneault gave sharply different accounts of what the latter told the former in 2023, when China’s actions in 2019 and 2021 were coming to light.

A CSIS briefing document dated Feb. 21, 2023, told the PMO that China had “clandestinely and deceptively interfered” in both elections, and cited 34 previous briefings for the PMO on that issue from mid-2018 to early 2022. But PMO chief of staff Katie Telford, her deputy Brian Clow and advisers Jeremy Broadhurst and Patrick Travers said they never heard CSIS’s most dire concerns when the spy agency met with them. Mr. Trudeau said no one relayed the concerns to him, and since he rarely reads written intelligence briefings, an in-person meeting or phone call was the “only way to guarantee, to make sure, that I receive the necessary information.”

The PMO aides were dismissive of Conservatives’ claims that China cost them seats, as was Mr. Trudeau when he testified to Justice Hogue. For instance, when asked about CSIS’s findings that a Chinese diplomat in Vancouver claimed to have helped defeat Mr. Chiu, Mr. Trudeau said officials might try to impress superiors by taking credit for things they had not achieved themselves. “Bragging is not doing,” he said.

Electoral officials Caroline Simard and Stéphane Perrault have faced intensifying scrutiny over how they addressed foreign interference in 2019 and 2021.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

Money and influence at the riding level

The commission heard about some forms of influence that are beyond Canada’s power to police, such as disinformation on the China-based social platforms WeChat and Douyin. But sometimes, foreign proxies organized within Canada, aided by Chinese money, under the radar of campaign-finance laws. Chief Electoral Officer Stéphane Perrault told the commission he looked into claims that China was reimbursing donors for supporting its favoured candidates, which is illegal. Mr. Perreault said he didn’t have the authority to pursue those cases, and the official who does, Commissioner of Canada Elections Caroline Simard, complained that CSIS’s confidential findings were inadmissible as evidence to punish wrongdoers.

When Canadians last went to a federal election in 2021, it's possible that 'a small number of ridings' were swayed by foreign interference, Justice Hogue found.Mark Blinch/Reuters

‘A stain on our electoral process’: The first Hogue report

Based on what she heard in Phase 1, Justice Hogue said in her May 3 report that interference tarnished the electoral process and “it is possible that results in a small number of ridings were affected, but this cannot be said with certainty.” That’s stronger language than what Mr. Johnston used, though, like him, she said the national results would have been the same in 2019 and 2021 regardless of outside influence. Justice Hogue also acknowledged that some intelligence about the interference “did not reach its intended recipient,” or was misunderstood by those who did get it, but she said there was no evidence of bad faith in this.

What’s happened since Phase 1 ended?

Is there a traitor in the House?

Separately from the Hogue commission, MPs and senators at the national-security watchdog NSICOP looked into whether any parliamentarians were involved in foreign interference, and concluded that some were “witting or semi-witting” accomplices to China and India. The public version of their bombshell report in June did not identify the politicians, and the government has ruled out releasing the names. Federal parties agreed to send the findings to Justice Hogue’s team for review, but leaders who have read NSICOP’s classified report disagree about how damning it is. The Greens’ Elizabeth May was “vastly relieved” that no current MPs were implicated, but the NDP’s Jagmeet Singh was not: “What they’re doing is unethical. It is in some cases against the law. They are indeed traitors to this country.”

One bill passed, but questions left open

Some anti-interference measures have already become law through C-70, a bill that got royal assent in June. It is now illegal, for instance, to help foreign agents enter Canada disguised as tourists, or to use “deceptive or surreptitious acts that undermine democratic processes,” such as meddling in candidate nominations on behalf of another country. CSIS also has more latitude to share sensitive information to avert interference. But crucial tools for enforcing these laws – a foreign-agents registry, and a transparency commissioner to oversee it – haven’t been set up yet.

Jagmeet Singh's federal New Democrats are no longer in a supply-and-confidence deal with the Liberals, which raises the chances of an early election.Christopher Katsarov/The Canadian Press

NDP throws election date up in the air

Passing bills was easier for the Trudeau Liberals when they had a supply-and-confidence pact with the NDP, which guaranteed its support in votes that would otherwise bring down the minority government. On Sept. 4, Mr. Singh tore up that deal, saying his party would vote with or against the Liberals on a case-by-case basis. That increases the chances that a federal election, previously due in the fall of 2025, could happen sooner. It is now less clear who will be in power to act on Justice Hogue’s final recommendations, or how a polarizing campaign could change parties’ positions on foreign-interference issues.

What’s happening in Phase 2?

Justice Hogue’s first report called on Ottawa to restore trust in democracy through “real concrete steps to detect, deter and counter” foreign interference. In Phase 2, she will ask witnesses what those steps could look like. The first hearings begin on Sept. 16, with a five-day series of policy roundtables with experts on Oct. 21-25. Check the commission’s website for the latest schedules and lists of participants.

The commission has to deliver its final report by Dec. 31.

With reports from Steven Chase, Robert Fife, Marieke Walsh and Kristy Kirkup