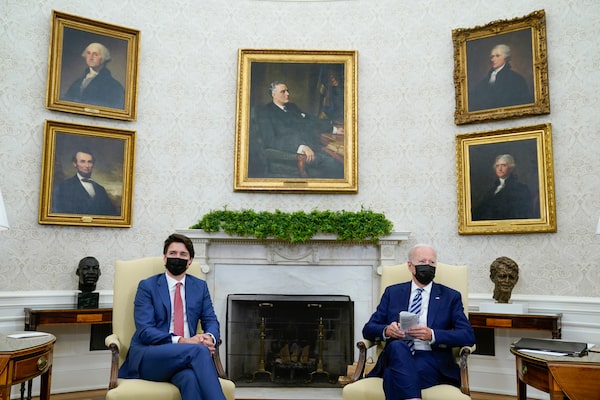

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau meets with U.S. President Joe Biden in the Oval Office of the White House on Nov. 18.Evan Vucci/The Associated Press

Thursday’s gathering at the White House wasn’t so much a North American summit as it was serial meetings of three leaders thinking about separate problems.

And for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, it was at best a not-Trump summit. He didn’t get the big thing he wanted on trade: a commitment from the U.S. to curb a “Buy American” proposal for electric vehicles that is now moving through Congress, and that has Canada’s auto sector worried. He had to settle for the hope that maybe, now that Joe Biden is in the White House, the new, friendlier President might somehow fix it, some day.

Will he? Will the U.S. President find some common ground that will ease Canadians’ fears?

“The answer is I don’t know,” Mr. Biden said as he welcomed Mr. Trudeau to the Oval Office. “And I don’t know what we’re going to be dealing with, quite frankly, when it comes out of legislation, so we’ll talk about it then.”

It wasn’t a Donald Trump threat. But it was the answer of a president who has a lot of headaches of his own – a “maybe later.” At a briefing, Mr. Biden’s press secretary, Jen Psaki, made “maybe” sound like “probably not.”

The night before, Mr. Biden had travelled to a GM plant in Detroit, where a “Made in America” sign was hanging to tout the very thing that Mr. Trudeau was coming to complain about – and that Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador is displeased about, too. Mr. Biden told workers that the policy would ensure “the jobs of the future end up here in Michigan, not halfway around the world.”

At the moment, the proposed U.S. EV incentives have Canadians worried that the jobs of the future won’t make it across the Detroit River to Windsor, Ont., or to Oshawa or Oakville. The proposed tax credits of up to $12,500 for American-made electric vehicles could lead automakers to set up their EV plants south of the border. This was, according to a Canadian government source, the first thing Mr. Trudeau raised with Mr. Biden behind closed doors. The Prime Minister obviously wanted a better answer.

But then, Mr. Trudeau’s Liberals still feel relief that they are no longer in the panicky days of a few years ago – when, for example, they once got word that then-president Donald Trump wanted to announce a U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA by the coming weekend. At least with Mr. Biden they have these summits, where they can discuss co-operation, trade matters, climate change, vaccines, security and so on.

Mr. Biden has his own headaches. The electric-vehicle incentives are a publicized part of the domestic agenda he is trying to push through his own fractious party and a divided Congress. Mr. Trudeau’s Liberals don’t want to see Mr. Biden fail, because that could help a Trump comeback. But then, some governments are starting to wonder if the Biden administration is using the fear of a Trump comeback as an excuse for not making concessions to the world.

The electric-vehicle issue isn’t incidental to a North American summit. In the eyes of Canada and Mexico, it is a violation of the USMCA trade pact, which all three countries signed in 2018 to succeed NAFTA.

That kind of trade disagreement hardly gave a sense that Mr. Biden was hosting a summit about a continental project. Much of it was spent in bilateral, rather than trilateral meetings.

Mr. Lopez Obrador, like Mr. Trudeau, spoke about North American supply chains and competitiveness, and he emphasized competition with China. But he and Mr. Biden also spoke a lot about migrants and migration: The U.S. President faces political pressure to control it, Mr. Lopez Obrador talked of accepting it.

Canada and the U.S. have their own complaints about Mr. Lopez Obrador’s economic nationalism. Mr. Trudeau’s government has complained that Mr. Lopez Obrador’s energy policy, which favours state-owned companies, will harm Canadian investments.

This was the first North American leaders summit in five years – even if it lacked the summit feel of some past Three Amigos confabs, which were held at Montebello, or Guadalajara, or at George W. Bush’s ranch in Waco, Texas.

This summit left the talk of North American integration and common cause a little lost among other things, especially Mr. Biden’s domestic political needs. For Mr. Trudeau, it was a summit with a U.S. president not putting regional trade high among his priorities, or rushing to fix Canada’s problems.

For subscribers: Get exclusive political news and analysis by signing up for the Politics Briefing.

Campbell Clark

Campbell Clark