Globe columnist Jeffrey Simpson is shown in 1988.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL

In his 43 years at The Globe and Mail and 32 years as a national affairs columnist, Jeffrey Simpson has written thousands of columns, published eight books and won all three of the nation's leading literary awards. Now, at the end of June, he will be retiring.

During his time in The Globe's comment pages, Canada has seen 10 federal elections, seven prime ministers and many defining moments of the world's modern history. Here are some decade-by-decade snapshots of how Mr. Simpson saw some of those events.

Aug. 11, 1984

Brian Mulroney's speech of a lifetime

Brian Mulroney and his wife, Mila, wave to supporters on election night on Sept. 4, 1984.

THE CANADIAN PRESS

Ladies and Gentlemen.

As we start this new day in your fair city, Mila and I want you to know how touched we are by your reception of me as a new leader.

Friends, there's a new day coming for Canada, when our young people can dream new dreams, a new day full of the bright promise of a new prosperity.

We need new harmony in this magnificent country to deal with the challenges of the new technology. We need a new spirit of co-operation so that those newly arrived on the labor market will find those new jobs our new policies will create.

We need a new respect for the taxpayers' dollar, new attitudes towards spending, new realism about the new economic environment, new ideas about how to confront the new problems of tomorrow.

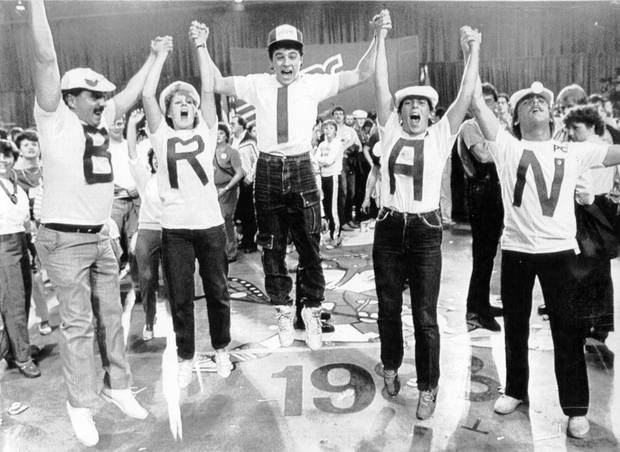

Mulroney supporters jump for joy at the party election headquarters on Sept. 4, 1984.

HANS DERYK/UPC

New policies will be required if new Canadians are to take their rightful place in our society. They need a new deal born of a renewal of those attitudes of tolerance and civility that characterized our ancestors when they built a new country.

We need new ideas in federal-provincial relations: a new council of first ministers, a new respect for provincial jurisdiction, a new conference on the disabled, a new conference on manpower training, a new conference on adult illiteracy, a new Tobacco Marketing Board – all new ideas I have proposed in the last 10 days, the cost of which I may announce when we get new figures from the Government or, more probably, after that new day for Canada the new Government will usher in after Sept. 4.

There is no shortage of new ideas in Canada. I have myself proposed a number of new ideas in this campaign, new ideas which are at substantial variance with the new ideas I once put before you.

What we need is a new dedication, a new wellspring of political will, a new commitment by new men and women in Ottawa, a new national understanding, a new appreciation of our common destiny, a new patriotism so that we can rekindle anew our love of Canada.

We need a new budget, to light a new and mighty bonfire of entrepreneurial activity, a new tax system to reward those who start new businesses, a new tax-collection system based on new principles, a new energy policy directed at encouraging new Canadian companies to find new sources of energy, new tax credits to create new jobs, new training opportunities, a new offshore energy policy to provide new revenues for our newest province, Newfoundland. We must expand the New Horizons program to give new dignity to our senior citizens. We need new faces in the civil service to help us implement our new mandate, and new Tory faces at the patronage trough, for there is no whore like a new whore. We need a new Senate with a new Tory majority, and a new High Commissioner in London and a new Ambassador in Portugal.

We need new productivity, new research and development, new markets, a new name for FIRA, a new respect for our American friends, a new defence policy, new uniforms for the armed forces, new rail lines in Atlantic Canada, a new fisheries policy, new help for our farmers, new assistance for pensioners, new respect for Parliament.

Friends, we have a new team with new policies that offer new hope for a new start, a new chance, a new harmony, a new dignity.

But I will not make new promises I cannot keep. So I must tell you that there will be no new clichés between now and Sept. 4.

Thank you.

Dec. 5, 1995

Federalists need a Plan B to show secessionists

A crowd passes around a Canadian flag at a Montreal rally on Oct. 27, 1995, three days before a provincial referendum on secession from Canada.

RYAN REMIORZ/THE CANADIAN PRESS

The federal government, as you would expect, is wrestling with how to keep Canada united. It has placed resolutions on Quebec as a distinct society and a constitutional veto formula before Parliament. A cabinet committee is searching for policies to stave off secession.

All this – and the work done by provincial governments – we might call Plan A. But the rest of Canada urgently needs work on Plan B, whose main objective would be to ensure that the rest of Canada never, ever finds itself ill-prepared for dismemberment.

Had the Yes side won the Oct. 30 referendum, the secessionists had thought deeply about how to achieve their aims in subsequent negotiations. The rest of Canada was utterly ill prepared.

Plan B aims to ensure that such a state of affairs never arises again. Plan B would see the rest of Canada think hard about how it would organize itself for secession negotiations, how it would define its self-interest, what it would seek to achieve in those negotiations and how it might organize itself as a country thereafter.

Some scattered work on Plan B is already at hand in academic studies and a few books. Happily, a variety of think-tanks and university groups are now resolving to work in the months ahead on various aspects of the terms Canada would insist upon if Quebec voted to leave.

The Reform Party joined the discussion last week by publishing what it called "realities of secession." These amounted to what the Reform Party thinks the rest of Canada should demand in any negotiations. They are quite a reasonable set of objectives, but they are by no means the last word on the subject. And they inevitably reflect just one element of English-Canadian public opinion.

The work on Plan B fills two critical gaps. First, it forces people to think hard about protecting the rest of Canada's self-interest. Second, it prevents the secessionists from arrogating unto themselves the right to interpret what the rest of Canada would think and do faced with its own dismemberment. So far, the secessionists have been brilliantly successful in telling Quebeckers what they can expect from the rest of Canada. Not surprisingly, the portrait they paint is almost entirely favourable to a painless realization of the secessionist project.

The intensifying focus on Plan B throughout the rest of Canada still lacks focus. In six months, there will be more studies and research at hand. Thoughtful people will have concentrated their attention on various projects, but the work will lie scattered in reports, studies and books.

What's needed, therefore, is a focus. Here's a modest suggestion about how to achieve it.

The English-Canadian premiers should work, of course, on Plan A – how to keep the country together. But they would be derelict in their duty to their citizens if they failed to think about protecting the rest of Canada's interests should the worst come to the worst.

Therefore, the premiers should ask a group of extremely distinguished Canadians, entirely from outside Quebec, to report to them later in 1996 on the issues raised by Plan B. This group of eminent people would sift through the existing and emerging research, commission its own, perhaps hold hearings just as Quebec's Belanger-Campeau commission did, and advise the premiers (and citizens) how best to protect the rest of Canada's self– interest in any secession negotiations.

The premiers need not endorse the report. They could remain at arm's length from it – that is, unless Quebeckers voted for secession, in which case the study would prove an invaluable guide. Such a report would be untouched by political considerations. It could not be claimed to be a partisan document or something thrown together for political purposes.

Rather, it would stand as what Quebeckers would likely face from the rest of Canada if they voted to secede. As for the fear that such a project might make secession more likely, that argument hardly applies after a 50.6-to-49.4 vote on Oct. 30.

Nov. 2, 2004

Pity a lawyer-filled country ruled by an Electoral College

Bush supporters wave American flags at the Ronald Reagan Building in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 3, 2004, as Democrat John Kerry concedes the election in a speech from Boston.

RON EDMONDS/ASSOCIATED PRESS

The United States is this amazing country that can send a mission to Mars, crack the genetic code, pinpoint a military target from miles above Earth, gather Nobel prizes every year, produce brilliant novels and wonderful music – but struggles to organize properly a national election.

Today, Americans choose their president and federal legislators, but how the election is organized – who can vote and how the ballots will be counted – remains a local prerogative.

No national body supervises a national election, as in other countries. A legion of lawyers – the United States produces more of this breed than any nation on Earth – is preparing to contest, if necessary, the results. Lawsuits have already been launched, and judicial rulings delivered, in key states such as Ohio. If the result is close, more lawsuits are probable.

Given the hanging-chad fiasco in Florida in 2000, and the Supreme Court ruling making George W. Bush president, it might have been expected that the country would review how it conducts its voting.

Improvements, in a manner of speaking, have been introduced. Still, in a large state such as Ohio, different counties will be using different methods, some of them quite confusing.

Various proposals have been made to standardize voting cross the country, but these have gone nowhere in the teeth of the curious U.S. preference for local arrangements.

Speaking of curious, there is also the matter of the Electoral College, a throwback to the early years of the republic that yielded a result in 2000 whereby the candidate with the largest number of popular votes failed to win the White House. It is entirely possible that the same result could happen today.

Shelves groan with books and articles recommending scrapping, or at least modifying, the Electoral College. Voters in Colorado are being asked today whether they want to keep their winner-take-all system for the state's Electoral College votes or apportion them according to each candidate's share of the popular vote.

Defenders of the status quo come disproportionately from small states that believe the Electoral College forces candidates to pay attention to them. They're probably right about that, but the flip side of the argument is that votes in big cities and some large states are bystanders in the national parade.

The Bush and Kerry campaigns, for example, have seldom, if ever, visited Los Angeles and San Francisco, Houston and Dallas, New York and Boston, and Chicago and Indianapolis, to say nothing of the entire South (minus Florida), because the Electoral Colleges votes in those states are a given. The Electoral College focuses the campaign into perhaps 15 states, instead of all 50.

Pity the people in those states. The parties will have spent an estimated $600-million on advertising. The bulk of that staggering sum has been funnelled into the "battleground" states. A voter in Republican states such as Texas or Indiana or in Democratic states such as California or New York might not have seen a single television advertisement because the parties didn't bother advertising there, whereas someone in Wisconsin or Florida has been bombarded with them.

Mind you, were the Electoral College scrapped in favour of an outcome based only on the overall popular vote, the cost of a U.S. campaign might be even higher. Candidates would have to buy ad time in the country's biggest markets, where it costs more than in Des Moines or Milwaukee.

Getting a grip on political spending has proved impossible in the United States. Occasional legislative changes designed to limit spending have generally failed, and never more so than in this impassioned election. The Republicans raised more money than the Democrats. The Democrats benefited more from third-party spending ostensibly to promote views on issues but, in fact, intended to benefit the Kerry-Edwards ticket.

There will be, as usual, a certain amount of clucking in the election's aftermath about these eccentricities of presidential campaigns, but not much will be done if the past is any guide.

The world's longest political marathon ends, barring subsequent legal challenges, as it began: with a nation divided following an exhausting, costly and bruising battle, and with most of the world eager to see George W. Bush defeated.

May 26, 2016

The Conservative challenge, post-Harper

Former prime minister Stephen Harper pauses while addressing delegates during the 2016 Conservative Party convention in Vancouver on May 26, 2016.

DARRYL DYCK/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Canada's Conservatives have been a remarkably quiescent lot since their electoral defeat seven months ago. No factions have appeared; no backstabbing has left blood on the floor. Anger has been bottled up and kept from public view.

It was not always so for the Conservatives' predecessors.

The Progressive Conservatives (remember them?) always turned their guns inward and fired after defeat. They sometimes fired at themselves while in power.

The fighting against the leadership of John Diefenbaker began while he was still prime minister. The leadership of Robert Stanfield was marked by continuous unhappiness from Diefenbaker loyalists and assorted other malcontents. Joe Clark, Mr. Stanfield's successor, never had a complete grip on the party. Usually out of office, the PC party never mastered the discipline of power.

Only Brian Mulroney's two smashing majorities quelled internal dissent, as did the leader's remarkable abilities at keeping his caucus happy, even in politically turbulent times.

As Mr. Mulroney's second term moved along, however, his coalition fractured with the creation of the Reform Party (and the Bloc Québécois). The right was hopelessly divided – a division that delighted the victorious Liberals.

So it might be argued that under Stephen Harper, who more than anyone put together the modern Conservative Party, conservatives experienced their longest continuous stretch of internal peace in at least half a century. And the peace has lasted, even in defeat.

Watch the highlights of Harper’s Conservative convention speech in under two minutes

1:53

On Thursday, in Vancouver, the whole party – and the country for that matter – will see Mr. Harper for the first time on a public platform since his rather weird election-night appearance last October. You might recall that rather than announcing he was resigning as party leader and/or leaving politics, he did neither. Instead, he issued a press release before he spoke announcing he was stepping down as leader, presumably not to give his adversaries the satisfaction of a watching a public admission of defeat.

Then Mr. Harper stayed on as an MP, seldom appearing in Ottawa and never speaking publicly in Canada, in the House of Commons or anywhere else. (He is expected to resign as the MP for Calgary Heritage before the fall.) He did apparently give one address last month at a meeting in Las Vegas organized by a casino mogul who is a fervent defender of Israel and right-wing political causes, as is Mr. Harper.

Because Mr. Harper resigned as leader immediately after losing the election, and then disappeared (as he had every right to do after so many years in the public eye, despite some media outlets demanding to know where he was and what he was doing), he removed himself from whatever firing line disgruntled Tories might have dreamed up for him.

When he addresses the party convention on Thursday evening, it would be difficult to imagine any mea culpa, but rather a recitation, as any leader has the right to offer, of what he believes were the accomplishments of his time in office.

As an amateur piano player, he could (but he won't) quote the Sinatra line, "I did it my way." The question before the Conservatives today, and for the future, is whether that "way" will be good enough, or whether changes will be required.

Almost every Conservative who has spoken publicly about the party's future agrees that at least stylistically there must be a change. The party as surrounded by enemies; the all-or-nothing attitude to debate; the shrillness and take-no-prisoners partisanship; the total lack of humour; the search for divisive "wedge issues" – these characteristics of the party under Mr. Harper are now almost universally acknowledged to have been counterproductive.

All the Conservative leadership candidates thus far announced, and those who will yet enter the contest, will agree on this critique. But beyond style, what about substance?

Mr. Harper did take a more ideological perspective on government (and foreign policy) than the predecessor party. The effect was to narrow the Tories' potential appeal, which worked only if their adversaries divided the non-Conservative vote and the base of the party was hugely mobilized.

The narrowing made internal discipline easier, since the Harper party had very few moderate Conservatives left. Amid national defeat, most of those who were elected are from rural and small-town Canada.

The commanding issue for the post-Harper party is how to broaden its appeal. The debate about the means to accomplish this objective has barely begun.