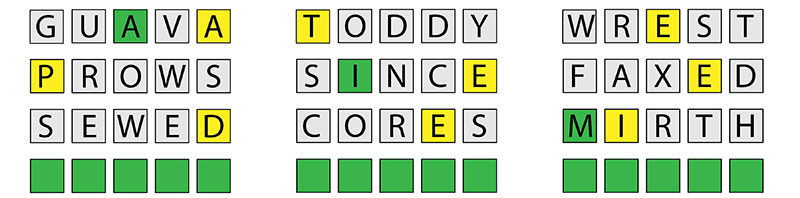

This is the first of three Wordle-style puzzles in this column, designed by the author. We've supplied three initial guesses for each; can you figure out the solutions? Try the quiz at the end.Illustrations by The Globe and Mail

Fraser Simpson creates the cryptic crossword in the Saturday print edition of The Globe and Mail.

Lately, internet users have both groaned and delighted as their social-media feeds and group chats have been overrun by the latest online craze. Messages filled with little checkerboard grids of black, yellow and green arrive with exclamations of celebration, relief or defeat.

The culprit? A rather modest website containing a simple five-letter word game called Wordle, an online logic guessing game that gives you six shots at divining a five-letter word, with zero hints for your first guess. Interest in the game, which was developed by Brooklyn software engineer Josh Wardle, has been growing for months, but perhaps reached its apogee this week as The New York Times announced it had purchased Wordle for an amount “in the low seven figures.”

So is Wordle a new classic, set to join the ranks of the crossword and its ilk? Past puzzle fads may give us a clue.

In Wordle, word-game fans might recognize older incarnations of popular puzzles with similar DNA. The 1950s saw the invention of a pencil-and-paper word-guessing game called Jotto, for example, which used four letters. I also used to watch a television game show, Lingo, which had similar gameplay and filmed its premiere season in Vancouver in the late 1980s. (You can find episodes of later iterations of the show on YouTube.) Other solvers might see a similarity in the logical nature of the two-player board game Mastermind, which uses sequences of coloured pegs instead of words. Akin to Battleship, one player has to blindly guess the order of pegs their opponent has chosen.

These games haven’t quite established themselves as ubiquitous classics in the way that the crossword, the Rubik’s Cube and Sudoku have. Each had its fad moment (in the 1920s, 1980s and mid-aughts, respectively) but what may have helped them transition into something more established was the accompanying emergence of self-styled experts and strategists.

When Rubik’s Cube became a big hit, a number of guidebooks appeared, explaining sequences you could memorize to make your solving faster. Sudoku strategy has proliferated online, and crossword fans have compiled lists of the most common short words – if you think about the interlock required in the standard American crossword, you’ll understand why vowel-heavy words such as AREA, ÉPÉE and UNAGI (eel, at a sushi bar) pop up so frequently. If a clue for a four-letter word refers to a musical instrument, it’s a pretty good bet that it’s an OBOE.

Wordle’s own self-styled experts have also come out of the woodwork, offering suggestions for the best starting words, for example – ROATE or STEAR, anyone? But during its fad moment, part of Wordle’s appeal has been its availability in the public domain and the ability of players to share results with anyone online, without revealing the answer (hence the colourful checkerboard tweets).

With its sale, the game now finds itself on a different trajectory from other puzzles such as Sudoku and the crossword, which are widely replicated with many variations online and in print. In one way, the purchase has solidified Wordle’s continued existence, but some disheartened devotees have balked at the prospect of it heading behind a paywall. The Times has said it plans to keep the game available for free – “initially.” Whither Wordle’s playability for all?

It might be something of a letdown in the short term, to see Wordle bought up by a bigger fish, but word nerds shouldn’t lose heart. As Jotto and Lingo before it, Wordle will likely be one in a long line of logic-based word puzzles to come.

d.