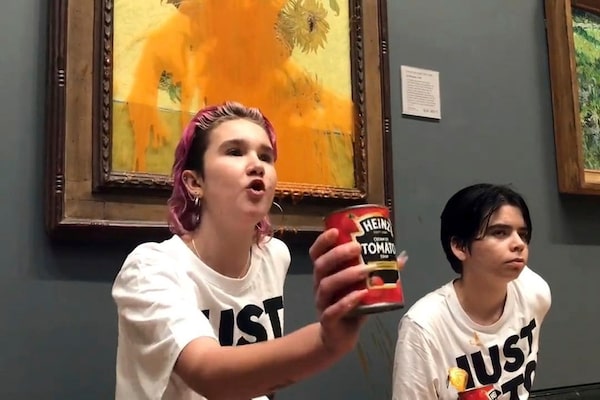

Two protesters who throw soup at Vincent Van Gogh's famous 1888 work Sunflowers at the National Gallery in London, on Oct. 14.Just Stop Oil/The Associated Press

The most polarizing aspect of the recent spate of “attacks” by climate activists against famous works of art has to be that demonstrators have chosen to use edible ammunition.

Have they seen the numbers on food inflation lately!? Everyone knows that if you want to get the proletariat on your side, you eat those mashed potatoes and hurl cheap water-based paint or some other type of budget-friendly projectile at that priceless Vincent van Gogh or Emily Carr. Otherwise, you end up looking desperately elitist and painfully out of touch.

These activists have readily acknowledged that their method for bringing attention to climate change isn’t exactly logical. “I recognize that it looks like a slightly ridiculous action,” Phoebe Plummer, one of the activists who threw tomato soup at van Gogh’s Sunflowers at London’s National Gallery, said after appearing in court. “What we’re doing is getting the conversation going so we can ask the questions that matter.” This is the theory behind many absurd and disruptive forms of protest: you can’t get people talking about your cause if you don’t get their attention first, and you don’t get their attention by calmly leaning over to your fellow gallery patrons and saying, “This Monet sure is beautiful, but you know what else is? Clean air.”

But does the theory of “any attention is good attention” really pan out? Some research, at least, says it does not.

One study by researchers at Harvard and the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict analyzed hundreds of major resistance movements from around the world over the last century. It found that non-violent campaigns were more likely to elicit popular support compared to violent campaigns, and they were also more likely to shift loyalties in favour of the protesters’ cause.

A 2017 paper from the Rotman School of Management looked at three different types of protests – about animal rights, Black Lives Matter and against former U.S. president Donald Trump – and found that extreme tactics that are successful in raising awareness also tend to reduce popular support. The researchers hypothesized that most people have trouble identifying with activists who employ extreme or destructive methods of protest. Observers don’t see themselves as the type to, for example, block traffic or splash paint on a building, which makes it much more difficult for them to relate to protesters who employ these methods. The researchers noted that there are exceptions to this rule, however, such as when extreme protests elicit unpopular responses from the state: a contemporary example would be Iranian security forces violently cracking down on women burning their hijabs in public.

What this suggests is that while the majority of patrons perusing the latest exhibits at the National Gallery in London will say that they are very concerned about climate change, the tomato-soup bandits could actually be hurting their cause by employing tactics with which regular Londoners won’t want to be associated. The trucker convoy protests earlier this year, which were purportedly about vaccine mandates, could be another example of this phenomenon; polling by Angus Reid showed that the border blockades and occupation of downtown Ottawa actually made people more inclined to support vaccine and mask mandates, not less.

The disconnect between the target of the protesters’ actions and the people or institutions against which they are supposed to be demonstrating could also be another factor negatively affecting their ultimate goal. Indeed, this lack of “action logic” – or the clear, immediately understandable message inherent in their actions – makes it difficult for observers to understand what they’re doing and why. It’s not hard to discern, for example, what animal rights activists are demanding when they wave images of wounded coyotes outside of a parka factory that uses animal fur on the trim of its hoods. But what do tomato soup and van Gogh have to do with climate change? Or maple syrup and Emily Carr? The answer is: about as much as bouncy castles and hot tubs have to do with vaccine mandates.

The difficulty in forming an effective protest is that grassroots movements tend to prioritize big splashes over strategy, particularly when participants are deeply passionate about their cause. Messages also tend to get diluted as protest movements grow; the Occupy Wall Street movement, for example, which was initially about undue corporate influence on government and elite business corruption, evolved to be a protest about just about everything, including Israel and Palestine, reproductive rights, police brutality and so on, to the point that it became difficult to recall why protesters pitched tents in Zuccotti Park in New York in the first place. Though the movement went global and lasted for months, it failed to achieve any significant tangible changes.

The same will likely be true for our soup-wielding, mashed-potato-hurling, maple-syrup-equipped friends. They’ve been getting people to look at, talk about, and ephemerally think about the climate. But in the end, all they’re doing is wasting food.