Bryan Gee/The Globe and Mail

Tom Rachman is a contributing columnist for The Globe and Mail. His fourth novel, The Imposters, will be published in June.

I need help.

Turning to my spiritual guide, Google, I type what I’m seeking: “the secret to happiness.” Before I can hit Enter, autocomplete drops down rungs of replies, resolving the age-old puzzle before my eyes:

the secret to happiness is low expectations

the secret to happiness is insensitivity

the secret to happiness is being good looking

Ah, yes: The internet is where you go for happiness, and leave with the opposite.

But such searches – online and off – feel more urgent of late, with the dark days of winter upon us, the pandemic still lurking, prices soaring, Putin invading, tech draining humanity from humanity, and the climate retaliating for what we’ve done.

(I promise: This article is about happiness. But first, I must confirm your suspicions.)

Awful feelings have been on the rise for a decade, according to the Gallup Negative Experience Index, surveying more than 125,000 people in dozens of countries, asking whether they suffered stress, pain, anger, sadness or worry the previous day. Meanwhile, the proportion of respondents defining their lives as the worst possible has quadrupled in the past 15 years.

Not all is bleak, though. Away from our fretting, experts have been toiling to crack the formula for happiness. If successful, they could transform society, alter the blather of politicians, perhaps even fix you (well, partly).

Personally, I’d welcome a revamp of society, of politics, and of me, a frowning fellow who’d hide in a cupboard rather than join a singalong of If You’re Happy and You Know It. To date, my formula for life could be summarized as tea, books and wallowing. I can’t entirely recommend it. Now Google fails me too.

So, I stand from my writing desk, pack a bag and seek answers overseas, flying to a land near the top of every happiness ranking: Denmark.

Pasta. As you suspected, the secret to happiness is pasta.

I’m wandering along cobbled streets in the Old Town of Copenhagen, through an area once flush with naval officers in 18th-century pomp till fire burnt the area to cinders, leaving it to rise again into a model of Scandi-prosperity: upscale design shops, understated residences, and the copper-green spire of a former church, now an arts centre that – in the cheery-earnest Danish way – shows works by kids and grownups alike.

What I’m hunting, though, is something deeper: a basement, to be exact. Finally, I spot a modest yellow sign with black letters curling into its smiley title: The Happiness Museum.

I descend down steep stairs to the entrance, past a gift shop of well-being merch (how-to happiness volumes, smiley-face mugs, upbeat tchotchkes), to a series of rooms on the hard science of this, from how location affects feelings, to the politics of happiness, to stats aplenty.

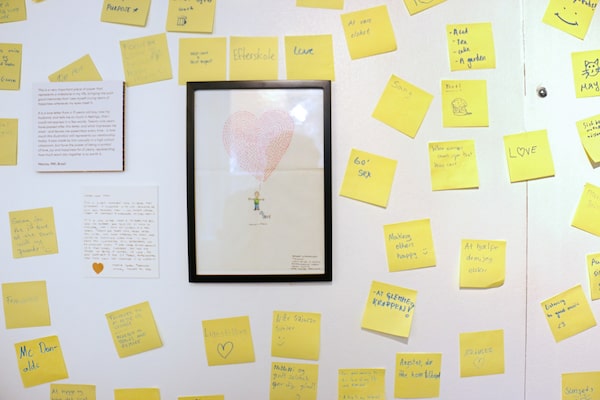

Most captivating is a room where previous visitors – invited to jot down the meaning of happiness – have scrawled their answers on Post-its and slapped them on the walls. After Pasta, I read Making music with others and Laughing in the middle of having sex. I hope the other person was laughing too.

Post-it display in The Happiness Museum, CopenhagenThe Happiness Museum

My reflections on that scene halt, for I’m led onward by the founder of this place, Meik Wiking (pronounced “Mike Viking”), a dashing 44-year-old Dane with greying beard, round spectacles and a pensive half-smile, as if modelling a brand of unpretentious Nordic sweaters.

Mr. Wiking – who founded the Happiness Research Institute a decade ago, then wrote an international bestseller, The Little Book of Hygge: The Danish Way to Live Well – points out that most of the Post-its cite two sources of happiness: beloved friends or beloved foods. He reads aloud an exception: Happiness is a good-quality lawnmower and a big lawn to mow, adding, “I completely understand that one.”

Evidently, people differ on the route to happiness.

Already in ancient times, philosophers bickered over what amounts to the good life, some rooting for hedonism, others counselling restraint. Aristotle said that chasing mere pleasures was the lot of beasts: Humans possess reason, so should act rationally for purposeful ends.

Religions added their views, often crediting the gods when happy events blessed humans, and blaming humans when disaster struck. The faithful were promised happiness in the afterlife. Other influential traditions included Buddhism, which advocates mental training to replace bitterness with compassion.

During the Enlightenment, thinkers pursued secular routes to happiness. The utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham characterized pleasure and pain as entries on a ledger, encouraging society to ramp up the first, suppress the second. “It is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong,” he wrote.

The utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham wrote 'It is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong.'WELLCOME LIBRARY, LONDON

When talk therapy gained popularity in the early 20th century, attention turned to the moods between our ears. According to Freud, hidden drives control us, making a mockery of our plans. As he informed patients (presumably after they’d paid for the session in full): “Much will be gained if we succeed in transforming your hysterical misery into common unhappiness.”

What all these centuries of prognostication shared was a lack of hard data: We didn’t know what worked. But progressively, the science of psychology grew more rigorous. And economists too began to study minds, not just wallets. In parallel, the opinions of society itself came into view through the practice of simply asking vast numbers of people: the poll.

An ambitious survey began in 2005, when Gallup sought to capture feelings around the world, including a vital measure of happiness conceived by the mid-20th-century Princeton psychologist Hadley Cantril. The puzzle that had long vexed moral philosophers – what does make us happy? – gathered empirical evidence.

“I, without irony, call myself Aristotle’s research assistant,” a founding editor of the World Happiness Report, University of British Columbia economist John Helliwell, tells me. Aristotle “was asking precisely for that evidence, about how people thought of a successful life. We now are able to fill that hole.”

The challenge when talking about happiness is figuring out which “happiness” we mean. You might feel sad because your ice cream hit the pavement – yet remain contented with your life. Equally, you could be jubilant upon digging into a fat tub of Ben & Jerry’s – yet grim about existence when considering the emptied container.

While happiness researchers consider how people feel at a given moment, a more sturdy measure is how satisfied they are with life over all. The annual World Happiness Report, for example, ranks countries by their life-satisfaction replies to the “Cantril Ladder” question: Imagine yourself on a ladder, where the bottom rung (number zero) is the worst possible life and the highest rung (10) is the best. Where do you stand?

According to the latest figures, the happiest nations are Finland, Denmark and Iceland, where the average life satisfaction is around 7½ rungs up the ladder. Nordic countries have dominated since the report began in 2012, commending their societies’ supportive institutions, high safety and mutual trust. (Cold weather – once you adjust to it – has little effect on well-being, it turns out.)

Countries on the wrong side of the World Happiness Report are poor, typically ravaged by civil conflict and corruption. The three lowest-ranked are Zimbabwe, Lebanon and Afghanistan, which is the saddest spot on Earth, its citizens averaging 2.4 out of 10. (If you’re wondering, Canada is high in life satisfaction at around 7, though this has declined over the past decade.)

Now that experts have data on well-being in different places, and can infer what helps societies flourish, the question is: Why aren’t we all doing that?

A version of this thought popped up a half-century ago, even before the facts were in, when a teenager in a remote Himalayan kingdom asked why money matters more than happiness.

Bhutan is a small, sparsely populated, landlocked Buddhist state between India and China, speckled with wild orchids, and rarely mentioned in the news. An exception came in 1972, when King Jigme Singye Wangchuck took the throne aged 16, and made a remark that helped inspire a global movement: “Gross national happiness,” he said, “is more important than gross domestic product.”

His isolated nation turned its attention to how citizens felt, and developed a National Happiness Index. To many, this sounded quirky and unserious. But over the decades, the academic study of well-being grew, particularly in the expanding fields of behavioural economics and positive psychology.

Still, economic growth remained the pre-eminent gauge of whether a country flourished. That shifted after 2008, when the global financial crisis provoked such fury that many doubted traditional measures of progress.

The phrase “beyond GDP” spread, and that little nation in the mountains won fresh attention. As it happened, Bhutan itself never became a misty paradise; it suffered ethnic violence and repression, and its population remains awkwardly not that happy.

Yet the country became a post-financial crisis inspiration, leading to a United Nations resolution in 2011, urging member-states to start measuring public happiness, and to act on the results.

In 2012, three distinguished economists – Jeffrey Sachs of the United States, Richard Layard of Britain, and Prof. Helliwell of Canada – followed up with the first World Happiness Report, which cleverly included national rankings, drawing headlines every year, and exerting pressure on politicians.

The appetite for this new approach is immense. When Yale offered a course on happiness, it became the most popular in the 300-odd years since the college’s foundation. Harvard has established a Center for Health and Happiness; Tsinghua University in Beijing set up a Happiness Technology Laboratory, and Oxford University founded a Wellbeing Research Centre. Academic papers on happiness gush out.

Among the insights (as suggested by those Post-its) is how important other people are. The lonely suffer more than just the blues: They’re deprived of a vital resource. Poverty is a major cause of misery too. But once you reach a comfortable level, more wealth brings little extra benefit. Kindness has benefits. And personality plays a role: Some are just born happier.

“The good life is a dish with many different ingredients in it,” says Mr. Wiking, of the Happiness Research Institute in Copenhagen. “We do need good coffee and good food; we need connection; we need to take a step back and feel happy with what we see. We also need purpose and meaning in life.”

The power of society is vast. If you compare the life satisfaction of immigrants with that of the local-born, the results are nearly identical, even if the newcomers hail from places where scores are half as high. In other words, it matters where you find yourself.

Here in Denmark, watching everyone biking around in apparent harmony, pastries at the ready, the value of a nurturing system is hard to deny.

Still, something bothers me. Do we actually want happiness?

I recall a philosophy course during my university days in Toronto, when a professor asked us to picture a machine that tricks you into feeling joy. Which of you, he asked, would spend your life in that machine? I glanced at my fellow students – not known for their aversion to hedonism – and expected hands to shoot up. None did.

We do want happiness. But we value something besides: reality.

Leaving my happiness guru at his museum, I resume my search around Copenhagen, this time seeking unhappiness. I find just the right place: a much-worn armchair, a psychotherapist glaring at me.

Dr. Anders Draeby – white-stubbled shaved head and a habit of lurching forward when he speaks, as if to lunge for a falling cup – recounts his crisis. As a younger man, he pursued money and success, and achieved each. But a decade back, aged 40, he felt empty, and found himself loitering before the grave of the 19th-century Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, author of such how-to guides as Fear and Trembling.

Day after day, Dr. Draeby returned to the grave, as if seeking something. Finally, he found it: This rumination, he decided, was itself the answer. He would devote his life to seeking truth, even if painful.

A problem with Western culture, Dr. Draeby tells me between seeing patients, is that we avoid dark experiences as we avoid dark rooms, hastily flicking on lights. If depressed, we chase fast cures, guzzle medication – anything to escape distress.

But the real sadness, he says, comes from asking oneself all the time: Am I happy, am I thriving, am I satisfied? Studies substantiate this: People who value happiness most are more likely to be depressed.

“We have created all of this science and technology in order to battle our fear, and take control of our destiny. But we do not see that it does not work,” Dr. Draeby says. “We have damaged nature, we have damaged the climate, we have damaged our own nature, because we think we are also machines that can just go on and on and on like that.

“The moment you begin to accept that suffering is part of life and you can learn from it, the fear disappears from suffering.”

Sorrows, I agree, can deepen a person. But sorrows can also destroy a life, without necessarily bringing insight.

Our culture is full of this conflict when selling the good life: self-care versus austere meditation; foodie tours versus paleo diets; retail therapy versus therapy therapy. We flee suffering – yet scorn those who’ve never endured it. This plays out in how we seek well-being for our kids, protecting them from every bruise (helicopter parenting) while believing they need hardship to flourish (tough love).

Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize-winning co-founder of behavioural economics, conducted happiness research for a while, but abandoned the field, baffled by the weirdness of humans. “I gradually became convinced that people don’t want to be happy,” he told Haaretz. “They want to be satisfied with their life.”

Prof. Kahneman found that we each contain two selves – and they disagree. The “experiencing self” perceives pain in a dentist’s chair or downs cocktails on a tense vacation. Then the “remembering self” constructs a narrative of what happened (inaccurately): how agonizing the filling felt; how that was the best trip.

Fascinatingly, the remembering self – so occupied with how we appear and what we achieve – dominates us. “In short,” Prof. Kahneman said, “people want to have a good story for their life.”

So, well-being experts must do more than find the formula to happiness. They must convince us to want it.

Prof. Helliwell – surely the smiliest 85-year-old in economics – beams at me from Vancouver via video-chat, gently explaining that media types such as me deserve blame.

“Economists typically say the individual knows everything, and then chooses according to that. Well, individuals don’t know everything. They’re prisoners of what they’re told,” he says. “People are hearing that material rewards are more important than the human ones, and they’re told that humans aren’t as nice as they are. So they end up with these two unhappiness-producing sets of beliefs.

“Part of the underlying essence of the well-being science,” he continues, “is that it will rebalance the base of credible information which is available to people when they’re thinking about their own lives, and about the kind of institutions they want to support.”

Schools should view education as more than just grades, considering pupils’ lives over all, and strengthening their psychological immune systems against depression and loneliness, Prof. Helliwell says. Prisons and elder-care homes should also follow well-being insights, while doctors should look beyond illness to consider patients’ happiness, “social prescribing” when someone is suffering.

“We have to move away from the idea that this is just soppy talk,” he says. “You have to rethink the way you do business.”

Businesses too should rethink business, given how much time – and anguish – people expend on jobs. Corporate types chatter about “employee well-being,” but often flail around with perks – free yoga in the conference room! – that bypass the problems, whether bullying managers and burnt-out staff; or employees whose wisdom is ignored; or work life invading private life.

“You cannot yoga your way out of these challenges,” says Sarah Cunningham, managing director of the World Wellbeing Movement, a non-profit founded last year to feed the mounting academic evidence to companies and government.

Businesses, she tells me, should measure employees’ well-being, and analyze whether the known drivers of workplace happiness are functioning. Here, decency and greed nestle neatly together, for happy workplaces are also more productive.

Governing politicians too have a direct interest in well-being, for happier people are more likely to vote for the incumbent. A counterpoint is that opposition candidates benefit by stirring up misery.

That has always been true, and legitimately: The challenger observes what ails society, and promises to improve matters. A corrosive element today is the politics of unending grievance, notable among populists such as Donald Trump, who draw support from the unhappiest yet have no plan for their well-being, so keep inflaming public misery while casting blame on purported “enemies of the people.”

Thankfully, other politicians are testing well-being in a positive sense. In 2018, the Wellbeing Economy Governments group formed, and today consists of Iceland, Scotland, Wales, Finland and New Zealand, whose Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, speaks not of finance in isolation but of “the well-being budget.”

“We’re embedding that notion of making decisions that aren’t just about growth for growth’s sake, but how are our people faring,” she said in 2019.

The British government also strives to consider public well-being when evaluating policy, following initiatives in 2010 from then-prime minister David Cameron. (Disastrous actions by his government and those that followed have seriously damaged Britain’s social fabric, its economy and its health care, showing that intentions alone don’t deliver the good life.)

In 2021, Canada issued a major quality-of-life strategy too, dubbed “Measuring What Matters,” in which the Department of Finance pointed out that a vast majority of people want to move beyond traditional metrics such as economic growth.

A useful new measure is the WELLBY, based on calculating the change in a person’s life-satisfaction score (zero to 10) per year. With this, officials can study the hard numbers behind happiness.

“Within 20 years, it will surely become the standard method of policy evaluation in more and more countries,” Prof. Layard of the London School of Economics wrote in 2021 with his colleague Ekaterina Oparina.

This could be the future. But I see obstacles.

First, politicians want results to brag about in the next campaign. But election cycles aren’t necessarily long enough to transform a fragmented society into a prosperous bunch of bike-riding Scandinavians in thick socks, sipping mugs of sustainable hot chocolate, and writing bestselling crime novels without any actual crime.

A second problem: Political factions define “well-being” differently. Should it include protecting the environment? Is the priority fighting poverty? What about mental-health spending? And inclusivity?

Advocates of happiness science will say well-being includes all of that. But government is about choosing – what to neglect, whom to focus on.

A third issue is that, in this polarized era, well-being risks becoming another wearisome left/right divide. While supporters of happiness science include conservatives such as Mr. Cameron, the former British leader, the most prominent politicians plumping for well-being initiatives nowadays tend to be progressives.

A glimpse of the possible divide came in Britain recently. When a notably right-wing prime minister, Liz Truss, took power in September, she openly sneered at those who care for anything besides GDP. “I have three priorities for the economy,” she said, “growth, growth and growth.” (Ms. Truss promptly crashed the economy, and lost her job.)

So it is that I fly home from serene Denmark to frazzled Britain, the season turning day to night again, energy prices so high that I put on another layer rather than put on a radiator, and therefore write these words with shivering fingers – only for my phone to terror-ping me with the latest news update: The UN chief says we’re doomed.

Once more, I need help, so open a web browser, typing, “is happiness … " Before I can finish, Google wants to autocomplete my thoughts:

is happiness a choice

is happiness a verb

is happiness on netflix

Happiness is not found on a screen, I suspect, much as we keep poking ours in hope. The well-being movement must contend with that too: Our source of nearly everything, from information to love, is also our leading source of falsehood and loneliness.

A disturbing chart looking at the behaviour of U.S. high schoolers shows how, as their internet use soared a decade ago, their in-person socializing fell, their sleep worsened, their happiness plummeted.

“We have not been paying attention, ladies and gentlemen,” the behavioural economist Andrew Oswald told a well-being conference last summer. “If governments had been tracking ‘feelings data’ for decades, I believe that our democracies would not be in the danger that they currently are in. And I regret to say that I think our democracies really are in danger.”

Still, I want to end on hope, not panic. I call up the British well-being expert, Prof. Layard.

“What are you here for? You’re here to create as much happiness as you can in the world,” he says. “I think this is an idea that children should be introduced to before the age of 10. A lot of the angst of adolescence would be greatly reduced if that was the reference point.”

I didn’t learn that lesson by age 10, or after. I chased success for my remembering self, and ended up with the life satisfaction of Albania.

Today can feel bleak. Pasta might not be the answer. But not all trends are downward.

As the data researcher Max Roser says: “The world is awful. The world is much better. The world can be much better.” All three claims are true at once.

We might improve society, our jobs, ourselves. We’re learning how.

My only question now is whether we humans – brilliant enough to crack the happiness formula – will have the sense to follow it.