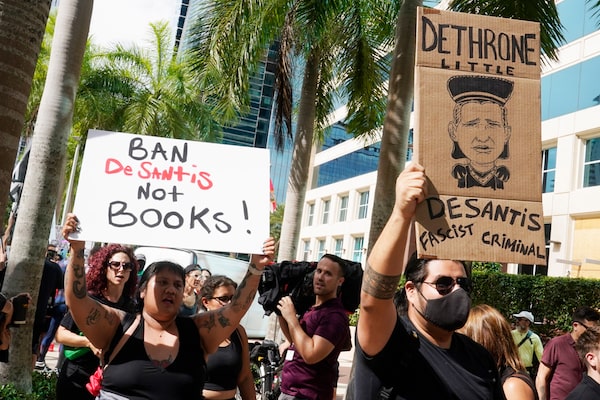

Protesters, dressed as characters from Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, rally in Sarasota, Fla., before a meeting of New College of Florida trustees about diversity policies. The German-language banner addresses Florida's governor and his sweeping education laws: '[Ron] DeSantis, Are you copying the Nazis?'Rebecca Blackwell/The Associated Press

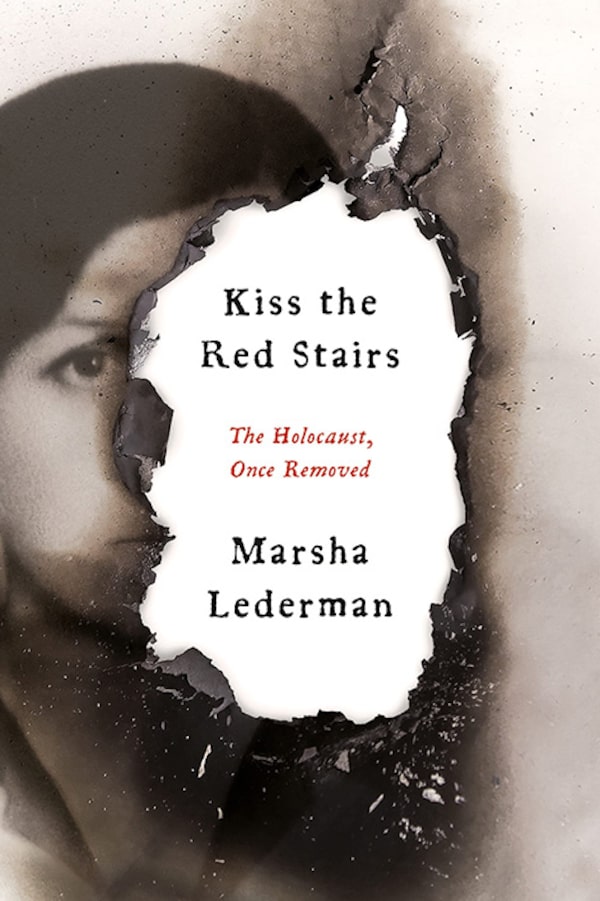

Marsha Lederman is a Globe and Mail columnist and the author of Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed.

On May 15, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed SB266, a bill that restricts certain topics from being taught in general education courses at state colleges and universities. No identity politics, no concepts related to systemic discrimination – racism, sexism, oppression, privilege. He made the announcement standing at a lectern with a sign in all-caps declaring: “Florida The Education State.”

Watching, I experienced what has become a familiar sense of the surreal. Like I have stepped into some sort of re-creation of a puritanical, or fascist, past. Or been punted into a near-future dystopia. Where is my bonnet? My armband? My bow and arrow?

Sex-education guides have been branded as pornography. Books with LGBTQ or BIPOC themes have been deemed immoral or, heaven forbid, “woke.” Holier-than-thou parents, pastors and politicians are railing at the professionals who educate their children. Librarians have been accused of “grooming” children to become gay or trans (as if that were possible – and the worst thing imaginable). Teachers have been emptying their classroom shelves, fearing they could be liable under the law for peddling child porn to students. There is real outrage over faux obscenity.

Did Margaret Atwood write this script?

The culture wars are taking place on sacred ground: my happy place, books. I have watched draconian bans enacted one after another after another, almost as if they were contagious. Or orchestrated. (Which, spoiler alert, they are.)

This anti-intellectualism has reached epidemic levels. The free-speech advocacy group PEN America found 1,477 instances of individual books banned, affecting 874 unique titles, in the second half of 2022, up 28 per cent compared with the first six months. The American Library Association reported an unprecedented 1,269 demands to censor library books and resources in 2022 – nearly double from the previous year.

Books banned or challenged in the U.S. include those by the usual suspects, Ms. Atwood among them. But also Milk and Honey by Canadian poet Rupi Kaur, The Bluest Eye by Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison, and Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl.

Florida has become an epicentre of this new wave of censorship under Mr. DeSantis, whose literary bona fides are matched only by his levels of tolerance. This month, PEN America, Penguin Random House, and some authors and parents filed a federal lawsuit against one Florida school district, alleging the unconstitutional removal of books from school libraries. The lawsuit notes that books by “non-white and/or LGBTQ+ authors” are disproportionately singled out, as are books with themes or topics related to race or the LGBTQ+ community.

This week, it was revealed that poet Amanda Gorman’s inauguration poem The Hill We Climb had been moved from a Miami elementary school’s shelves to the middle-school section, after a single parent called for its removal. “I’m gutted,” Ms. Gorman wrote in a statement.

Amanda Gorman delivers a poem at the 2021 U.S. presidential inauguration. A Miami library recently restricted the poem after a complaint.Patrick Semansky/The Associated Press

We are in a future I could never have imagined even just a few years ago. And where is this trajectory taking us? What will things look like a few years from now?

But it’s happening in America, we like to reassure ourselves. (At least I do.) I’ve been watching this go down from the perch of my progressive Canadian superiority.

However, censorship is not going to be contained in the U.S. by an imaginary line on a map. How could Canada not be affected? Infected?

“There’s literally been an explosion of challenges to intellectual freedom, to books, to programs in Canada,” says James Turk, director of the Centre for Free Expression at Toronto Metropolitan University. “I think it’s been significantly inspired by what’s happening in the United States.”

The issue has dominated the workload at the Centre, which now has a searchable database to track challenges at libraries across the country.

“We’re seeing it all over Canada,” publisher and author S. Bear Bergman told me. “It’s terrifying. And it’s dangerous.”

On May 24, the day of Ron DeSantis's presidential campaign launch, protesters march through Miami near a hotel where his donors were expected to meet. The Florida Governor's sweeping legislation restricts how Floridians are taught about race, gender and social injustices.Marta Lavandier/The Associated Press

The new bans

This is not a new story, of course. Throughout history, books have been banned, trashed (literally, metaphorically) and burned by authoritarian regimes wishing to police the ideas contained in them, from the Bible on down.

No Canadian has had more firsthand experience with this suppression than Ms. Atwood, whose novel The Handmaid’s Tale is a most-banned-books-list staple – and whose red-caped handmaids have become symbols of protest in these authoritarian times.

“It’s a well-known pattern,” Ms. Atwood told me recently, when we spoke about book banning. “It has to do with who gets to say who does and reads and thinks what.”

She reminded me about past campaigns to ban other Canadian classics, including Margaret Laurence’s The Diviners (the sex, the vulgarity). And Ms. Atwood pointed out the open letter to the Judson Independent School District, which she included at the back of her 2011 book, In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination. With her signature dry humour and wicked intellect, Ms. Atwood thanked the Texas school board for dedicating themselves “so energetically” to banning The Handmaid’s Tale.

“It’s encouraging to know that the written word is still taken so seriously,” she wrote. She added that free expression of opinion, “last time I looked, was still the American way, though that way is under pressure.”

If it were ever thus, things have reached a new, alarming state.

A library box in Houston, dubbed the Little Banned Library, contains books the library says have been challenged by Texas schools.Callaghan O'Hare/Reuters

Emboldened in the Trump era and activated during the pandemic, groups of far-right anti-intellectuals (and anti other things) have formed, claiming to be working to protect children and uphold family values.

Values of which families, one might ask.

As for protection – yes, indeed. This is about protection – of power structures. Of a status quo that has been challenged by movements wishing to dismantle established systems and build new, better ones that give voice to marginalized populations.

This new, polarizing censorship is not meant simply to divide, but to uphold existing divisions.

What’s also different now is the scale. The internet has fuelled the escalation, allowing people to connect with others who have similar ideas. Libraries and school boards have long dealt with individuals questioning a book’s appropriateness, but now the challenges are coming in droves, with campaigns organized by groups, such as Moms for Liberty and No Left Turn in Education, that provide parents with form letters and lists of books they should denounce.

These large, well-funded and well-connected groups – with the support of politicians like Mr. DeSantis – recruit ideological soldiers at the local level by preying on parental fears, ranting about “obscene” material and “child pornography” to whip up hysteria. They then basically hand those parents a script to do the dirty work in their own school districts.

An analysis of book challenges in 2021-22 published by The Washington Post this week found that a small number of people were responsible for most of them. Individuals who filed 10 or more complaints were responsible for two-thirds of more than 1,000 challenges examined.

Protesters, left, and counterprotesters watch as people bring children to a drag-queen story hour at a public library in Mobile, Ala., in 2018.Dan Anderson/The Associated Press

Social media makes it easy to share and amplify the outrage. And for the fury to transcend borders.

The group Action4Canada (“We are committed to protecting … FAITH, FAMILY and FREEDOM”) lists 99 Canadian chapters on its website and offers notice-of-liability form letters, ready for printing, with instructions on how to serve them to warn educators of criminal consequences.

“This Notice of Liability is to alert you, if you are not already aware, that your participation in making available explicit/pornographic books to minors and/or facilitating in the exploitation and/or sexualization of minors is unlawful,” one form letter states.

Prof. Turk dismisses these notices as “bogus.” The people who write them “don’t know the law,” he said. But the group is being heard.

In one recent case, A4C took a complaint to the RCMP in Chilliwack, B.C. The Serious Crimes Unit investigated and determined that the content – including It’s Perfectly Normal, a book about puberty and sexual health, and Ms. Morrison’s The Bluest Eye – did not in fact meet the legal definition of child pornography.

This week in Manitoba, meanwhile, trustees of the Brandon School Division listened in a high-school gymnasium for hours as constituents spoke overwhelmingly against a call to remove books that deal with sex education, gender identity and contain LGBTQ content.

“The children you are trying to protect will die,” Jason Foster, who is trans, told the standing-room-only crowd, which included People’s Party of Canada Leader Maxime Bernier.

The proposal had been made at a previous meeting by former school trustee Lorraine Hackenschmidt. “We must protect our children from sexual grooming and pedophilia. The sexualization agenda is robbing children of their innocence,” she said. Her presentation was applauded by attendees, according to The Brandon Sun.

“To insinuate that you have the right to set boundaries for other people’s children is asinine,” Trustee Jim Murray said in the early hours of Wednesday morning, before the board voted against establishing a committee of parents and trustees to review books.

Disputed works are displayed at a Banned Book Library in St. Petersburg, Fla., earlier this year.Jefferee Woo/Tampa Bay Times via AP

The people seeking bans often “portray themselves as nice, middle-class moms who … want to do something about this. These wonderful apolitical people who just want to protect their kids,” says Prof. Turk, who spent his career in education before founding the Centre.

“People who are raising these objections are not just all crazy, bad people,” he adds. “They’re entitled to express their views. What they’re not entitled to do is to censor and prevent other people from seeing different views.”

Many of the people pushing for these book bans have also been fighting for “freedom” vis-à-vis vaccines and masks.

The group Stand 4 Freedom NB was formed by New Brunswickers concerned about “the heavy-handed and anti-democratic approach to COVID-19 mitigation.” It is now actively warning about “the sexualization of our children” in schools.

Among the publications challenged in Canadian public libraries in 2021-22, according to Freedom to Read, was a COVID-19 Information Guide.

A woman, wearing a face mask and gloves, browses at the Vancouver Public Library's central branch in July, 2020, its first time reopening with limited services after the COVID-19 pandemic began.Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press

Canadian stories

S. Bear Bergman is a Regina-based author of books for children and adults who describes himself as a “queer trans man and a father of three.” He was invited this spring to read to kindergarteners at a local elementary school. But there was a delay that day. “Two parents,” he explains, “pulled their children out of school for the afternoon and were in the principal’s office, irate that a known transsexual – that would be me – was there to indoctrinate their children.”

The books on Mr. Bergman’s agenda were M is for Mustache, a Pride-themed alphabet book (“O is for Out on the street with our songs, our families”) by Catherine Hernandez; and Bell’s Knock Knock Birthday, a counting book with illustrations featuring gender-fluid characters, which author George Parker dedicates to queer families. Both are published by Mr. Bergman’s company, Flamingo Rampant.

During our conversation, Mr. Bergman brought up another frequently challenged picture book: And Tango Makes Three. Based on a true story, it’s about two male penguins who raise a baby penguin in a zoo. Tango has been challenged for promoting homosexuality and using its cute themes to be “insidious,” according to the Toronto Public Library’s Book Sanctuary, which lists materials that have been targeted for censorship.

“I’m here to tell you that the penguins are not at the bathhouse in their leather outfits,” Mr. Bergman says, “which is how these people make it sound.”

He continues: “I believe that these right-wing people fully understand that. And what they really are aiming for is stigmatizing our identities, our lives, our experiences, and making children afraid again of being able to come out, receive support, be their whole healthy fantastic selves,” he said. “That’s the whole move here, right?”

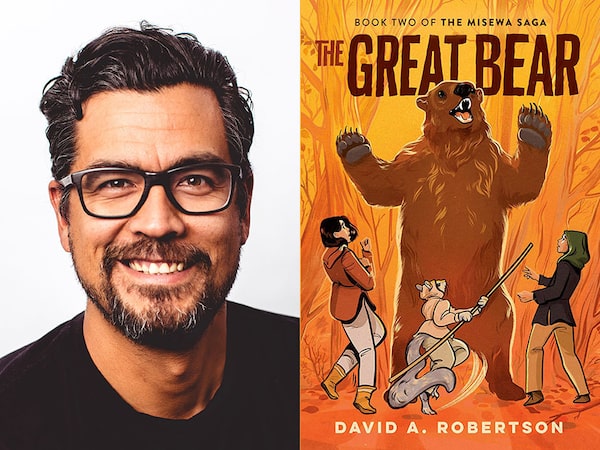

David A. Robertson is the Cree author of The Great Bear, a young adult novel.Handouts

David A. Robertson, a Governor-General’s Award winner, made headlines when his YA novel The Great Bear was removed by the Durham District School Board last year. A concern had been raised that the book could be harmful to Indigenous people – which was gutting to Mr. Robertson, who is Cree. The book was returned to shelves after outcry from the public, and his publisher, Penguin Random House Canada.

“I wasn’t happy with the outcome because they didn’t learn anything,” Mr. Robertson told me recently. “It’s great that my book was put back, but I don’t want it to happen to another book.”

Vancouver-based author Raziel Reid has also been targeted. After his YA novel When Everything Feels Like the Movies won the Governor-General’s Award in 2014, there were calls for the prize to be revoked, including a petition.

During a Scotiabank Giller Prize panel about book bans this spring, Mr. Reid shared a recent experience with a PEI high school. Mr. Reid was on Zoom, speaking into the void, with no camera on the students who had gathered in the cafeteria for his hour-long talk. When he finished, he learned that the feed had been cut about halfway through because of concerns about the explicit content. He continued to give his presentation, speaking to no one.

He was furious at how this was handled, but also cognizant of the environment in which it occurred.

“I think, for a teacher to cut a presentation, it speaks to the pressure that they face from parents to toe a certain moral line.”

When I asked Mr. Reid whether Canadians should feel safe from this U.S. wave of book banning, he answered before I could finish my question. “All of my experiences with book bans and censorship have taken place in Canada.”

Raziel Reid visits Vancouver's Mountain View Cemetery in 2015, where he wrote part of the book When Everything Feels Like the Movies.Jeff Vinnick/The Globe and Mail

The number of formal challenges in Canada is nowhere near what the U.S. is experiencing. At the Toronto Public Library, for instance, there were nine challenges to books in 2022. The review process for a challenge involves a committee of librarians reading the book and contextual information, such as reviews. They must leave their own politics at the door.

“Your own personal beliefs are not always going to align,” says manager of collections development Matt Abbott, who leads the TPL’s committee. “That is our job. That is an important component of intellectual freedom, which is a core value at a library.”

The TPL also received complaints last year about its drag story time programs.

As anti-trans sentiment rose in the U.S. (this week, Montana banned people dressed in drag from reading books to children at public schools and libraries), these events began being targeted here too, despite having gone on in some cities for years.

“Do any of these people know what’s happening in a drag story time?” says the Ontario Library Association’s Michelle Arbuckle, who chairs the Freedom of Expression committee for the Book and Periodical Council of Canada, which runs Freedom to Read Week. “If you watch RuPaul’s Drag Race, that’s not what’s happening at a drag story time.”

An ugly protest can get a lot more attention than filling out a form. And do a lot of emotional damage.

In Calgary last February, the Reading with Royalty program was disrupted by protesters who made their way into the event, shouting homophobic and transphobic slurs.

The drag event had to be paused. But it’s back. “We are committed to reflecting our community in the programs that we offer. This is a program that’s about kindness and inclusivity,” Calgary Public Library CEO Sarah Meilleur told me.

“It’s an opportunity for kids to look beyond some of those gender stereotypes and embrace identity and self and feel like they matter. And our strategic plan is that everyone belongs at the library.”

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LJPWJ5JTHBEAXLH6YN5KROKT7M.JPG)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/QN63W67FMZAVZKFWWS2ZIXYGCU.JPG)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/PNH64UV7V5GVNFOYAVWI2L35GM.JPG)

Anne Frank, Maus and me

I packed my sense of smug superiority into my carry-on as I headed to Florida for spring break. Part-time home to many Canadian snowbirds, the Sunshine State has become a book-banning epicentre under Mr. DeSantis, who would like to become U.S. president.

One of my destinations was Books & Books in Key West, the bookstore co-owned by Judy Blume, who has been the target of censorship battles since the publication more than 50 years ago of her seminal novel Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret – which deals with menstruation.

Among the titles the store had on display when I visited was the American Library Association’s Read These Banned Books: A Journal and 52-Week Reading Challenge.

I spoke to Ms. Blume later over Zoom, not long after a bill was introduced that would prohibit Florida public schools from teaching about sexual health, including menstruation, until Grade 6. “We live in a state with a Governor who is just making everything really dreadful,” she told me.

Mr. DeSantis has famously railed against what he calls “woke indoctrination” and has targeted school curricula and books – especially those dealing with critical race theory and LGBTQ issues.

Some Floridians aren’t having it. “Parents have the right to choose what their children read,” said Lourdes Martinez, a customer I met at Sandbar Books in Key Largo. “It’s not up to the school board. It’s a First Amendment right.”

Ms. Martinez, who lives in Destin, Fla., is a voracious reader. “Some of the books that are banned, it’s ridiculous.” She cited Maus, Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust.

Art Spiegelman's Maus chronicles the Holocaust experiences of his parents.Mario Anzuoni/Reuters

Last year, a Tennessee school board banned Maus, which is about Mr. Spiegelman’s parents’ wartime experiences and how that trauma played out tragically in his own home. The book depicts Jews as mice, Germans as cats.

The McMinn County school board pulled the book not just because of the difficult subject matter, but because of language (“bitch,” “god damn”) and, I can’t believe I’m even typing this, nudity. The depiction of a naked (illustrated animal) character.

“We don’t need this stuff to teach kids history,” school board member Mike Cochran told the meeting where Maus was debated. “We can teach them history and we can teach them graphic history. We can tell them exactly what happened, but we don’t need all the nakedness and all the other stuff.”

Readers like Ms. Martinez aren’t buying it. “If you don’t learn history, it’s going to be repeated.”

And this is where it gets even more personal. Some frequently targeted books, including Ms. Blume’s novels, were instrumental in my formative years. But also, especially, the diary of Anne Frank.

This book is very dear to many readers. But for me, it hit close to home. My parents survived the Holocaust and I related to Anne on a deep level. If those events happened now, I told myself as a kid, it could be me, writing in that attic. Because of her, I started keeping a diary. Would mine be published, I sometimes thought, after the Nazis rose back to power and sent me to a concentration camp? You could say that Anne Frank posthumously planted the seed of an idea that, decades later, saw me explore the Holocaust and intergenerational trauma in my own book.

Marsha Lederman is the author of Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed.McClelland & Stewart

When I learned about the Anne Frank bans (most recently, an illustrated version was removed from a Florida high-school library after being challenged by a member of Moms for Liberty), I figured the difficult subject matter must be the issue. Tough for kids to read about this teenager spending years in hiding only to be discovered and sent to her death.

But no. To quote the TPL’s Book Sanctuary: “This book has been banned due to a short entry where Anne discussed her sexuality and genitalia as she was going through puberty. Myriad attempts have been made worldwide to ban this book for that entry.”

More recently, Florida education officials revealed they had rejected dozens of textbooks – approving only 66 of 101 submissions. They initially approved only 19, but revisions were made in some of the rejected texts. Turned-down submissions included two about the Holocaust.

Coincidentally, I am supposed to be in Florida again when my memoir, Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed, is released in the U.S. this August. I’ve considered trying to organize a book signing while there. But thinking (obsessing) about developments in that state, I began agonizing over a particular passage. In my research, I had learned that Jewish men and women in Radom, Poland, where my mother lived, were rounded up by the Nazis on Yom Kippur, 1939, and forced to clean windows and remove paint from a factory.

“The Germans did not supply rags for this job,” I wrote. “The men were forced to use their prayer shawls, the women their underwear. (What if they were menstruating, I wondered as I read this.)”

Among the most treasured comments I have received from readers has been: This book should be taught in schools. Could that sentence about menstruation prohibit that? In Florida? Elsewhere?

Hypothetical as this scenario might be, I shared my concern with Prof. Turk. There was no way my Holocaust book could find itself censored because of a mention of menstruation, was there?

“Of course it could,” he said.

At Anne Frank House Museum in Amsterdam, photos pay tribute to the teenage Jewish girl who, in the 1940s, wrote a diary while her family hid in this building from Nazi occupying forces. Today, that diary still faces censorship in some jurisdictions.Eva Plevier/Reuters

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/DJBE36J2E5BC3KHWV3KV75MLNY.JPG)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/2JGK5GIU4ZFCXKM67R62TFMS3U.JPG)

The big chill

The most concerning, if fleeting, thought I had as I considered my memoir in the context of the culture wars was: If I had known about this when I wrote the book, would I have included that parenthetical detail about women and their periods? I mean, it was just speculation. How important was it really?

Well, very important, in fact. But could I have convinced myself otherwise?

This is what this climate does: it chills. It can make authors second-guess. It can make publishers revise textbooks, as we just saw in Florida.

Raziel Reid has been having trouble finding a publisher for his latest manuscript, a fictional account of the Jeffrey Epstein saga told from a feminist perspective. “People are afraid of it,” he says. Will it be deemed immoral? Especially in this moment? “Every publisher has to answer to the consensus of the market.”

And when it comes to booking authors, Mr. Bergman worries about schools making less challenging choices.

“That’s the silent chilling effect that this foolishness and nonsense produces,” he says. “Next time they choose an author to come in, there’s always the calculus of: Is this going to produce another set of irate parents in my office screaming about the gay agenda? And do I have the personal and institutional resources to deal with that?”

It may be a badge of honour to have your book banned; it can even increase book sales. But it’s not anything anybody wants to go through. And what could it lead to?

“If I were in one of those states I’d get a big billboard and say ‘Too hot to read’ and I’d sell a lot of copies,” said Ms. Atwood (who does not have to worry about book sales). “So it always backfires to a certain extent. Unless it’s such a ruthless regime that they find every single copy of that particular book and burn them. That’s what happens next.”

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/XTVNUJTDHJKT7PYGMBY2LXURWA.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/QWTWCXTH5NJKLIJGCJCXXO47P4.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/WDPRIGISIZJ2NLTNKGD4DYNZQM.jpg)

‘It’s going to happen more and more’

It’s a cliché to say that books have never been more important. But I am going to say it anyway.

In an increasingly dumbed-down society where anyone can publish anything on social media, mis- and disinformation is a click away, and the halls of power are populated with ignorance, books can provide a refuge of intellectual sanity.

Not always, sure. But access – true freedom – must be protected.

Because this isn’t going away. “It’s happened in the States and now it’s happening in Canada. And it’s going to happen more and more,” says Mr. Robertson, who is also editorial director of a new Tundra Book Group children’s imprint dedicated to publishing Indigenous writers and illustrators. “So what people have to do is be ready for it.”

The first step is to ensure that libraries have appropriate policies when it comes to intellectual freedom, says Prof. Turk, who is training library staff across the country to deal with this issue. “I’m being run off my feet.”

And ensure those policies are being followed, says Mr. Robertson, still reeling from his experience in Durham.

Readers can also help.

Go to the library, take out books, buy books. Read challenged books. You can find lists in lots of places, including the TPL’s Book Sanctuary. See for yourself.

Want to help others see for themselves? Read banned titles with your book club. Put copies in little free libraries.

Tell a librarian you love them! Seriously – an e-mail or word of gratitude goes a long way when you’re being called a groomer and pedophile on the regular.

Contact government officials, write to your school board. Pre-emptively express your support for libraries and for freedom of intellectual expression.

We can attend as many Freedom to Read Week events as we like (every February; they’re great) but that kind of pleasant, passive advocacy may not be enough to turn the page on this scary moment.

It’s time to make a fuss, Mr. Bergman says. Consider not just contacting your school board, but running yourself.

“This campaign of hate can only be countered by people who are not hateful also getting loud about not being hateful,” he told me.

“The support has to reach the vigour of the detractors.”

Further reading: More from The Globe and Mail

iStock/Getty Images

Lists from Globe Books

39 fiction and non-fiction books to read this spring

27 titles for every type of young reader

10 Canadian writers share their favourite independent bookstores

Marsha Lederman on books

We cannot turn the page on our commitment to public libraries

To create a better future, students need an education about race