These weary and emaciated Canadians were prisoners of war from December of 1941, when they fought the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong, to August of 1945, when Japan surrendered.Handout/The Canadian Press

Tim Cook is senior historian at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, and author of 12 books, including his three-volume history of Canada and the Second World War: The Necessary War, Fight to the Finish, and The Fight for History.

Canada declared war on Japan before the United States did. It had every right to do so, for even though the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor is commonly viewed as Japan’s entry into the Second World War, it was just one of many military campaigns that the Japanese Empire conducted on Dec. 7, 1941. Indeed, at roughly the same moment as Imperial Japanese aircraft were bombing the battleships at the naval base in Hawaii, some 2,000 Canadians were engaged in fierce combat with Japanese soldiers in the British colony of Hong Kong.

The Canadians in Hong Kong were serving in defence of the British Empire, which was vulnerable after a series of humiliating defeats against Germany in the first two years of the war. Even though Canada had full control of its foreign policy from the 1931 Statute of Westminster, it agreed to send two battalions to Hong Kong – a decision that has haunted many for 80 years.

Despite the British senior military command studying the problem and concluding that the colony of Hong Kong could not be held against a sustained Japanese attack, the generals, along with British prime minister Winston Churchill, nonetheless chose to reinforce the Hong Kong garrison in the hope of dissuading the Japanese.

It proved a futile gesture. Japan had been aggressively threatening its neighbours and had been at war with China since 1937, with its military leaders seeking to carve out a powerful empire.

Canada was asked to send soldiers in the early fall of 1941. General Harry Crerar, who wanted to support the Crown, made the case to cabinet. The national defence minister, J.L. Ralston, was a veteran of the Great War, and he also felt that the Canadian army should contribute soldiers.

With little intelligence-gathering ability, prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King felt pressured to agree.

On Nov. 16, 1941, two Canadian battalions – Quebec’s Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers – arrived in Hong Kong, along with a small brigade staff and two Canadian Army Nursing Sisters. The contingent was known as C Force.

The British colony consisted of the island of Hong Kong and the New Territories on the Chinese mainland, with the core of the population of over a million, including vulnerable war refugees from the Chinese-Japanese war, in the port city of Kowloon. The island and mainland were separated by the Lye Mun Passage, which was a little less than a kilometre wide at its narrowest point.

The British plan of defence was to meet the enemy on the mainland, fight a delaying action of about two weeks, and then fall back to the island, where the troops would hold out until reinforcements arrived by sea.

Canadian soldiers set up a post on a Hong Kong hillside before the colony fell on Christmas Day, 1941.The Associated Press

The battle

When the Japanese struck at 8 a.m. on Dec. 8, 1941, the colony’s defenders – British, Canadian, Indian and Hong Kong militia soldiers – were caught flat-footed. Despite being aware of a possible Japanese attack, the British commander took few precautions. Planes were destroyed on the ground and the battle-hardened Japanese forces, moving fast and light, drove hard through the allies’ prepared positions. The British general, Christopher Maltby, had poorly situated his defenders, with almost no mobile reserve, and within a week they’d been driven back to the island in a disorganized retreat.

The Japanese also struck throughout Southeast Asia and the Far East, but nothing was so shocking to Britain and Canada than the sinking of two British capital ships, Prince of Wales and Repulse, off of modern-day Malaysia. Japanese dive- and torpedo-bombers sent them to the depths on Dec. 10, devastating losses to British prestige and its ability to project power. There would be no support or reinforcements for the defenders at Hong Kong.

As the defenders prepared to hold the island against Japanese assault across the open water, Maj.-Gen. Maltby again showed much ineptitude, dividing his forces into sectors, with almost no central reserve. Nor did he guard the limited water supply, the key to a prolonged defence.

When the skilled Japanese soldiers attacked across the Lye Mun Passage on the night of Dec. 18, they broke through the Indian positions and surged across the island.

It was a chaotic dogfight from there, with the two Canadian battalions thrown into attack, defence, and counterattack. Maj.-Gen. Maltby told the Canadians not to worry about holding the high ground, recounted one Canadian, because the Japanese “will not attack over hilltops and mountain tops.” And so high points on the island – positions such as Mount Parker, Mount Butler and Jardine’s Lookout – were captured by the Japanese early in the battle, where they held significant advantages in launching attacks, situating mortar fire, and in defending against counterattacks.

“The situation is getting worse,” wrote Corporal George (Blacky) Verreault, a signaller with the Royal Rifles, on Dec. 19. “Their machine guns are spitting deadly bullets. … More bombs, more airplanes. We are trapped like rats. We can’t escape. We’ve been told that the [Japanese] do not take prisoners. What a way to die.”

The Globe and Mail's front page from Dec. 19, 1941, reports on Japanese advances in Hong Kong.The Globe and Mail

The Japanese advanced relentlessly to sow confusion. The Canadians were ordered to recapture one battle group holding Mount Butler. On the morning of the 19th, three platoons from the Winnipeg Grenadiers assaulted up the steep slope, driving forward, throwing grenades, shooting and bayoneting the enemy. They made deep inroads, but the Japanese counterattacked, using the observational advantage to better co-ordinate their assault.

As the infantrymen from Manitoba were driven back, one of the surviving leaders was Company Sergeant-Major John Osborn, a 42-year-old First World War veteran who time and time again held off enemy assaults to allow his comrades to retreat. He was bleeding freely from a wound to the arm but kept fighting. The Japanese closed in as the Grenadiers were trapped in an untenable position. A grenade landed among a group of Canadians. Sgt.-Maj. Osborn threw himself on the grenade to absorb the blast. He was killed instantly. “It was the bravest thing we had ever seen,” wrote Private William Bell, who survived because of Sgt.-Maj. Osborn.

The Canadians were captured soon afterward and Sgt.-Maj. Osborn’s body was lost on the battlefield. For his courage and leadership, he was awarded the Victoria Cross, the British Commonwealth’s highest award for gallantry, and the first for Canada during the Second World War.

Sergeant-Major John Osborn's set of Victoria medals.Courtesy of Beaverbrook Collection of War Art / Canadian War Museum

There was another week of intense combat. Although the written record of battle for this period is sparse, when the Japanese commanders recorded “strong opposition,” “fierce fighting” and “heavy casualties,” they were frequently referring to fighting against Canadians. Still, the Allies were forced to surrender Christmas morning.

The Japanese soldiers had won a significant victory, but they dishonoured themselves in its aftermath. Japanese soldiers executed a number of wounded soldiers on the battlefield and raped civilian women on the island. “I cannot bring myself to write about what happened between the 18th and 25th,” recounted Canadian Private T.S. Forsyth of the surrender. “All I can say is I saw too many brave men die. Some of my best friends died beside me. It is hard to put in to words.”

The Canadians suffered 290 killed, while 493 soldiers were wounded. All who lived were captured. The survivors of C Force were marched off to fight a new battle for survival, as they faced four years of unspeakable horror in prisoner of war camps.

Japanese forces parade through Hong Kong in 1942 on horseback.The Associated Press

The prisoners

Over the next four years, Japanese-held prisoners faced starvation, beatings and execution. Canadian POWs were forced into barbed-wire-enclosed camps in Hong Kong and, later, a group was sent to Japan as slave labourers.

In the camps, the Canadians adjusted to a new life of brutality and repression. The Japanese guards humiliated the prisoners at every turn. Canadians were struck with rifle butts, beaten with sticks, or kicked and punched for the slightest infractions. A former Japanese-Canadian serving in the Imperial Japanese army, Kanao Inouye, took special delight in brutalizing Canadians: The Kamloops Kid, as he was known to the Canadians, beat and abused prisoners on a whim, breaking bones, smashing in teeth and killing several vulnerable men.

To further break the will of their captives, the Japanese overlords systematically starved the prisoners, who subsisted on small portions of rice, rotten meat and fish heads, with desperate men forced to eat grass, bugs and maggots. Once healthy Canadians were reduced to gaunt scarecrows. The prisoners, wrote Canadian Leo Berard, “appeared as if some vampire had sucked all the blood from them, with the dead blue skin and eyes with a deep distant look.” Another Canadian, Sergeant Lance Ross, kept a secret diary through much of his ordeal. On Feb. 18, 1942, he wrote, “I believe we are going to starve to death.”

Men in fragile health succumbed to the mistreatment and malnutrition, and soon diseases. Dysentery was a great killer. The lack of vitamins from the gruel-like meals led to Beriberi disease, and prisoners saw their bodies retain fluid and swell up to grotesque sizes; others suffered burning sensations in their feet. Teeth fell out of decaying gums. Bodies became covered in weeping sores. Parasitic worms infected almost everyone and could be seen squirming in feces.

Amid this terrible suffering, the Japanese deliberately withheld medicine. The few doctors in the camps had to treat men who were dying before their eyes with only aspirin. With no money to bribe the Japanese guards, sick and weak Canadians willingly stepped up and let the doctors pull their gold teeth from their mouths to allow for the purchase of medicine.

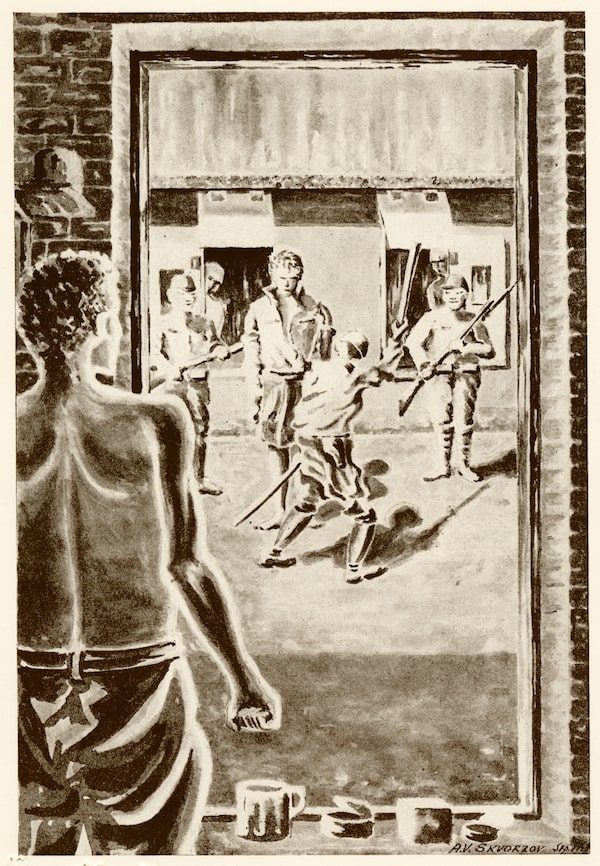

Life in the Sham Shui Po internment camp, as drawn by Russian expat Alexander Skvorzov, who was in Hong Kong's volunteer defence force when Japan invaded.Alexander Skvorzov. Courtesy of Beaverbrook Collection of War Art / Canadian War Museum

Some Canadians tried to escape, but there was nowhere to go either in Hong Kong or Japan. Savage beatings were meted out to all who were caught. Sergeant John Oliver Payne of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, a 23-year-old from Fort Rouge, Man., was executed, along with three other Canadians, when he was caught escaping in the late summer of 1942. Before they were murdered, Japanese military soldiers bound their bodies with barbed wire and beat them to a pulp with bats.

And yet the will to survive was strong. Prisoners played sports when they had the energy, usually for a few days after the periodic Red Cross packages arrived full of sweets. There were debating clubs and even theatre shows. Men with artistic talents painted and taught others how to do so, often with material scrounged from around the camps. Most made lists of things they would do when they returned home. All dreamt of food and loved ones.

Overworked and underfed, the Canadian POWs desperately held on, buoyed by the American military forces that were closing in on Japan through their joint amphibious operations that captured islands and the relentless bombing of its cities. The Canadian prisoners slowly became aware that the war was coming to an end, but their jailers warned the emaciated prisoners to expect no freedom. When the Americans finally came, sneered the Japanese, the Canadians would be the first to be executed. No one was ever going home.

Germany’s defeat in May, 1945, hastened the end of the war against Japan, which came three months later. The two atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when combined with months of American bombs on Japanese cities and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan, finally persuaded the Japanese Emperor to seek a surrender. It came on Aug. 15, 1945.

A few days before that, the Canadian prisoners, spread over several camps, noticed that their guards were drifting away. Most Canadians were near death from starvation, but some gathered together sharpened sticks for a last stand against the Japanese that they could not hope to win. And yet, on the day of surrender, the last Japanese guards removed their uniforms and skulked off.

The Canucks found that, against the odds, they had survived the intolerable.

Qualitatively and quantitatively, the treatment of the Canadians in Japanese hands was far worse than it was for those soldiers, sailors, and airmen who fell into the clutches of the Nazis. The death figure of Western Allied prisoners in Japanese camps was 27 per cent, whereas 4 per cent of Allied prisoners died in German camps. Of the 1,700 or so Canadians who survived the 1941 battle, 264 additional Canadian POWs died in captivity as a result of systematic abuse, torture and execution. The 1,418 survivors carried physical and mental scars for the rest of their lives.

One of the Canadian POWs, William Allister, used art and a diary to endure captivity until the war's end. He would continue to re-examine his war experiences in art and memoirs until his death in 2008.William Allister. Courtesy of Beaverbrook Collection of War Art / Canadian War Museum

After the war

Kenneth Cambon, a young rifleman who had served in the Royal Rifles of Canada as an 18-year-old, wrote in his diary of the end of the war: “I have literally grown up in a prison camp. Most of all my experience has been on the more unpleasant side of life … starvation, sickness, cruelty, robbery, torture, depravity … all overshadowed by death.”

But the liberated Canadians came home in late 1945. They were aged beyond their years, their health shattered by willful neglect, physical hardship, and unimaginable psychological trauma. Many were riven by disease and had fading eyesight or unidentifiable ailments caused by systemic starvation.

Most of these veterans also carried invisible trauma. “There was no counseling, no advice, no awareness that we might act or feel differently,” recounted William Allister, who kept his sanity in the camps by painting and writing a detailed diary.

The federal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King was focusing on the peace, not the war, and it especially wanted to forget the Hong Kong disaster. The government also had little appetite in prosecuting Japanese soldiers for war crimes, leaving the work to the Americans. Eventually about four dozen Japanese soldiers were brought to justice for crimes against Canadians, but most were freed within a decade. The only death sentence was carried out against the Kamloops Kid, Kanao Inouye. After a lengthy trial, he was hanged for treason in August of 1947.

Mr. Inouye outlived many of the Canadian veterans, who began to die from their wartime abuse after arriving back in Canada in late 1945. One veteran, for instance, died within a week of returning home to his family after four years of dreaming of being reunited.

A battery of medical studies of veterans revealed systemic poor health; over time, lowered life expectancy for the Hong Kong veterans was calculated to be 15 to 20 years below the national average.

The state nonetheless refused to offer any special compensation to these suffering veterans. Administrators and civil servants even withheld pensions, saying the visibly sick veterans could not prove their illness was a result of service. Where was the documentation, they asked? It could have been a Monty Python skit if it hadn’t been so cruel.

Graves of Canadian soldiers in Hong Kong in the 1940s.Handout

With few able to understand their experience in Hong Kong, the survivors formed the Hong Kong Veterans Association (HKVA) in 1948. They banded together as they had done in the war to provide solace and camaraderie, and they pressed Ottawa for more generous pensions. But it took until 1958 until the government finally relented and the POWs received an additional 50 cents a day in pension -- hardly generous by any means.

Why didn’t Ottawa demand a formal apology and monetary compensation from Japan, for the abuse and illegal slave labour? In short, politicians were not interested. Japan rapidly rebuilt after the war and it became a major trading power that Canada did not want to offend. But unlike Germany, which apologized for its crimes, paid restitutions, and taught its young people about the past, Japan for decades refused to address its wartime actions.

The Royal Canadian Legion and the HKVA made case after case to Ottawa to provide proper compensation, and it was only in 1971, when there was an overhaul of veterans’ pensions, whereby the Hong Kong veterans received a guaranteed minimum pension, although it was still below the poverty line. It had taken the better part of three decades for Ottawa to even acknowledge the physical harm of the war years; hundreds of the Hong Kong veterans had already died by this point. With pensions settled, and later augmented over the years, the surviving veterans continued to petition for an official apology from Japan.

In 1988, the Canadian state finally recognized its historic wrong to Japanese Canadians for their forced relocation from their communities and the massive infringements of their civil liberties during the war. Hong Kong veterans, meanwhile, wondered why they continued to be ignored by Ottawa. Finally, in December of 1998, 350 surviving veterans and 400 widows received financial compensation for the slave labour and reprehensible treatment.

The descendants of the Canadian veterans who formed the Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association in 1993 kept up this battle, even as their fathers and grandfathers died. One of their first sustained campaigns was against the now deceased British general Christopher Maltby, who, while in a prisoner-of-war camp, had written an official account of the battle. To justify the defeat, and to perhaps deflect the considerable fault that had been directed to him for the colony’s defence, he had blamed the Canadians for his failure. It was a gross twisting of the history. The Canadian veterans refused to accept the judgment, which was released in full by the British government in 1993, and they were supported by many Canadian politicians. After a war of words, the British apologized and the Maltby report was condemned.

Prime minister Stephen Harper and a veteran visit Hong Kong for a 2012 Remembrance Day ceremony.Bobby Yip/Reuters

The aging veterans continued to press Ottawa to demand an official apology on their behalf. After years of pressure from multiple countries for its wartime actions that ranged from mass and multiple atrocities to the forcing of women into sexual slavery, Japan’s apology to Canada’s veterans finally came on Dec. 8, 2011. With conservative elements in Japan opposing the apology, it was reduced to a “statement of regret” – unsatisfactory, to many veterans.

The Canadian survivors had already taken matters into their own hands to help with the healing. Refusing to forget their comrades, and aware of their dwindling numbers, a memorial was erected in Ottawa. It was unveiled on Aug. 15, 2009, the 64th anniversary of VJ Day. About two dozen of the 90 surviving members made the trip to Ottawa to renew faith with old comrades in front of the six-metre-long wall, clad in black granite and inscribed with the names of Canadians who fought in the battle. Paid for by the HKVCA, it remains as a site of memory and a space to bear witness.

In this year, the 80th anniversary of the battle, fewer than half a dozen Hong Kong veterans remain. They are outliers as most of their comrades are gone, lost in the battle of 1941, during the brutal four years in the prisoner of camps, or in the decades-long struggle for proper compensation and an official apology.

There will be no fourth battle for these veterans. But there should be for the rest of us: a continuing fight to remember this service and sacrifice.

Scout troops take part in a ceremony in Hong Kong earlier this month to mark the battle's 80th anniversary.James Griffiths/The Globe and Mail