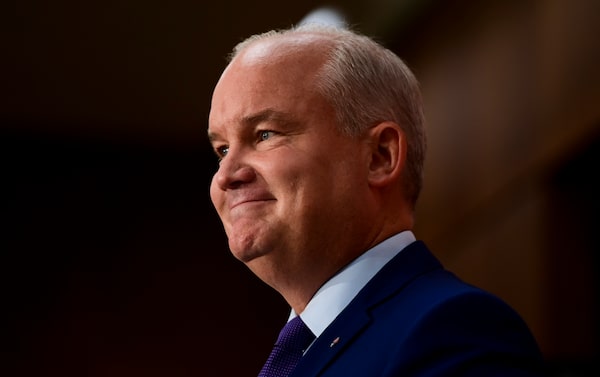

Erin O'Toole holds his first news conference as Conservative Party Leader on Parliament Hill on Aug. 25, 2020.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

It’s been barely a week since Erin O’Toole was elected Conservative leader, and already the press gallery has helpfully laid out his agenda for him.

He has to introduce himself to Canadians before the Liberals can “define” him. He has to unite the party, while turning his back on the social conservatives who elected him. He has to reach out to voters beyond his base, while still offering a meaningful alternative to the governing Liberals. And he must do all this in the shadow of an onrushing election campaign.

Steady on. There will almost certainly not be an election this fall, though a spring campaign is a stronger possibility. He has time enough to make himself better known; if he does not have much name recognition, neither does he come with much in the way of baggage. The party is not noticeably fractured; Mr. O’Toole won handily, and not as the champion of one wing of the party over another but precisely because he positioned himself closest to the party’s centre – blue enough, thanks to a hasty image makeover, to satisfy the right, without making himself repugnant to moderates.

The supposed “courting” of social conservatives amounted to little more than a vague rhetorical feint. In concrete terms, he promised them nothing. He did not have to. He was not Peter MacKay, and that was enough. This is the great, obvious secret of conservative politics, obscured though it may be by Liberal spin and media hysteria. The so-cons do not have the numbers to press their agenda, and they know it. (They have, it is true, disproportionate influence in the process of selecting a leader, but only because of the party’s obtuse insistence on using leadership campaigns as membership drives.) All you really have to do to secure their support is show them some respect, or at least not treat them like pariahs, “stinking albatrosses” and the like.

Yes, but his campaign slogan was “Take Back Canada.” He denounced things like “cancel culture” and called himself a “True Blue Conservative.” Isn’t that just awful? Not really, no. Promising to “take back” the country is bog-standard rhetoric for anyone campaigning in opposition to the governing party, though it is more usually heard from politicians on the left, accustomed as they are to asserting ownership of the national idea. You can find references to it online issuing from at least two former NDP leaders, the Young Liberals of Canada and the nationalist firebrand (and founder of the National Party of Canada) Mel Hurtig, among others. “Canada is back” is a variant.

I think the harsher tone Mr. O’Toole adopted during the campaign had less to do with sending coded ideological signals to one corner of the party or another than toughening up his persona generally. People in the party knew him as an affable, old-school pol, adept at the greasy arts of ingratiation and compromise. They also wanted to know whether he was a fighter, someone who could withstand attacks from his enemies or make new ones if he had to. (This was perhaps the gravest doubt about MacKay.) With one notable exception – his backflip on subsidies to the energy sector – he showed that he could.

The image that emerges, combining exposures from before, during and after the campaign, is of that rarity in Conservative politics – a relatively normal person. Mr. O’Toole comes across as a professional, serious but agreeable, bland but not guileless, unburdened either by Andrew Scheer’s crippling insecurity or Stephen Harper’s stewing resentments. In policy terms, he might best be described as a Mike Wilson Conservative, stolidly centre-right, less interested in the culture wars – beyond the ritual nods to crime (against) and guns (for) – than sound finance and free markets.

That at least would seem to be his default position. The more praiseworthy planks in his leadership platform – opening up Canada’s protected air and telecoms sectors, desubsidizing the media – show a willingness to take some risks, beyond the status quo. The more disgraceful parts – abolishing the carbon tax, preserving supply management, pandering broadly to Quebec nationalists – suggest he is not wholly the prisoner of principle.

Which direction he will take the party is thus unclear. The air is thick with talk of “fundamental rethinks” of “broken economic models,” mostly from people who never cared for them to begin with but have found the pandemic a useful prop to make their case. This will nevertheless be only too tempting to a certain kind of Tory. Rather than revisit the Conservatives’ knee-jerk opposition to carbon pricing or their dangerous flirtation with populist nationalism, Mr. O’Toole will be counselled to keep both, but dump the fiscal conservatism, the better to outbid the Liberals for Central and Eastern Canadian votes.

I wish I could say he was not open to it. I wish even more I could say it wouldn’t work.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.