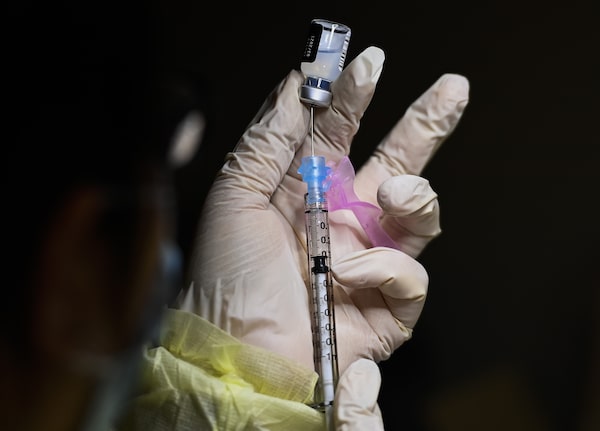

A pharmacist technician fills the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 mRNA vaccine at a vaccine clinic in Toronto, on Dec. 15, 2020.Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press

Myths and lies were circulating among us long before the coronavirus appeared. Some were vile and racist, such as the idea that Barack Obama was a Muslim who was born in Africa. Others were dangerously misleading, such as the notion that the measles vaccine could cause autism. Others – Elvis is alive; the moon walk was faked – were just silly.

The international health emergency over COVID-19 has produced a new blizzard of misinformation. This one may be the most dangerous of all.

All manner of conspiracy theories and wild rumours are flying around. According to one, Bill Gates is plotting to use the vaccine to implant traceable microchips in our bodies. Another posits that the vaccine will alter our DNA. Still others hold that – despite the overwhelming consensus among scientists and health authorities that the vaccines are safe and effective – getting the shot will make people sick.

The skeptical mood of the times has made it easier for such nonsense to spread. Opinion polls have been showing for some years that confidence in established institutions and sources of information has declined. A general climate of anxiety about supposed health threats is another factor. So is the rise of social media, which turbocharges the rumour mill and sends fake news pinging from phone to phone.

When will Canadians get COVID-19 vaccines? The federal and provincial rollout plans so far

The obvious danger is that scare stories will dissuade large numbers of people from getting vaccinated. That would blunt the impact of the vaccination campaign and prolong the pandemic. If 75 to 80 per cent of the population gets vaccinated, says Anthony Fauci, the veteran expert on infectious diseases who has become the face of the U.S. fight against the virus, then the pandemic can be tamed fairly quickly. If, as some polls suggest, only half of the population gets vaccinated, “then it’s going to take much, much longer to get back to the kind of normality that we’d like to see.”

We could have many thousands added to the pandemic’s death tally because of such a delay. So it is not an exaggeration to say that defeating the fear mongers and conspiracy theorists is a matter of life and death. But defeat them how?

One idea is that we should simply ignore them. Rather than dignify their fabrications by responding, just let them rant and they will burn themselves out. That doesn’t seem to be working. As the first injections of the vaccine were administered this month, the fevered exchange of twisted facts only grew more intense.

Another idea is to silence them. Under pressure to squelch the spread of scare stories, Facebook and Twitter say they are taking steps against the misinformation going around their platforms. But with so many ways of sharing and posting, it is next to impossible to put a lid on nutty ideas these days.

A final theory is that governments should simply override the doubts and fears of citizens and make vaccination mandatory. That could backfire, fuelling suspicion and stirring up an even wider revolt.

Far better to confront fake news head on. The best reply to bad information is good information. The best reply to junk science is real science.

Though the fear mongers have managed to disseminate their messages far and wide, the battle is far from lost. Health authorities and government leaders should be using their podiums to hammer home the message that the vaccine is safe, that getting inoculated against the coronavirus is the best way for people to protect themselves and their loved ones, and that the crippling lockdowns will end faster if everyone lines up for that jab in the arm.

They should use every platform and medium at their disposal. While social media help falsehoods go viral, they can spread truth, too. Officials should be up front about the (small) risks that come with vaccination, such as the possibility of allergic reaction, but also point out that millions upon millions have been safely vaccinated against smallpox, polio, diphtheria and other ailments over many decades.

Prominent people can help by lending their voices to the campaign for widespread vaccination, as the environmentalist David Suzuki did when he said that he would get the vaccine “in a flash.” Celebrities and leading political figures can set an example by volunteering to get vaccinated publicly as soon as their turn comes. Ordinary people can pause to check the source before they hit “share” on a dubious post.

Some will persist in believing the misinformation all the same. It is dismaying to see how many are willing to swallow even the weirdest and ugliest stories. But they are not the majority. If authorities marshal their facts, sense and science will prevail.

The initial COVID-19 vaccinations in Canada and around the world raise questions about how people react to the shot, how pregnant women should approach it and how far away herd immunity may be. Globe health reporter Kelly Grant and science reporter Ivan Semeniuk discuss the answers.

The Globe and Mail

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.

Marcus Gee

Marcus Gee