Elamin Abdelmahmoud/Handout

Elamin Abdelmahmoud is the author of Son of Elsewhere: A Memoir in Pieces, from which this essay is adapted.

It took two stopovers and 19 hours of total flying time for me to become Black.

I left Khartoum as a popular and charming (and modest) preteen, and I landed in Canada with two new identities: immigrant, and Black.

When the friendly customs agent stamped my passport and said, “Welcome to Canada,” he left out the “also, you’re Black now, figure it out” part. In retrospect, it would’ve been immensely helpful. Having lived 12 years as a not Black person – which is to say, a person entirely unconcerned with his skin colour – you can imagine it was a jarring transition to make.

Without an instruction manual, I was left to my own devices to figure this whole race thing out. And luckily, I had one thing going for me: The place I had just moved to was one of the whitest cities in Canada. This was going to be great.

The population of Kingston, Ontario, is estimated to be about 85 per cent white. Kingston is so white, way too many people say things like “my Black friend.” Kingston is so white (how! white! is it!), it has a town crier who is not only one of its most recognizable faces, he also won a title at the world championship of town criers. Lots of Kingstonians know this fact. They will tell it to you at parties.

All of this is to say: Kingston is not the easiest place to settle as a new immigrant. It’s not exactly a gentle introduction to a new land. It’s for good reason that most new immigrants to Canada find themselves in a major metropolis – a Toronto or a Montreal or a Vancouver. The idea is, when you have more people who look like you, it’s easier to recognize how a place can become home. By contrast, in Kingston the whiteness was overwhelming.

When we arrived in Kingston, Baba (my father) made a point of introducing us to the other Sudanese families. All in all, there were 11 families, a small constellation of people who looked like me and could speak like me and were, too, constantly aware that we were far from what we considered home.

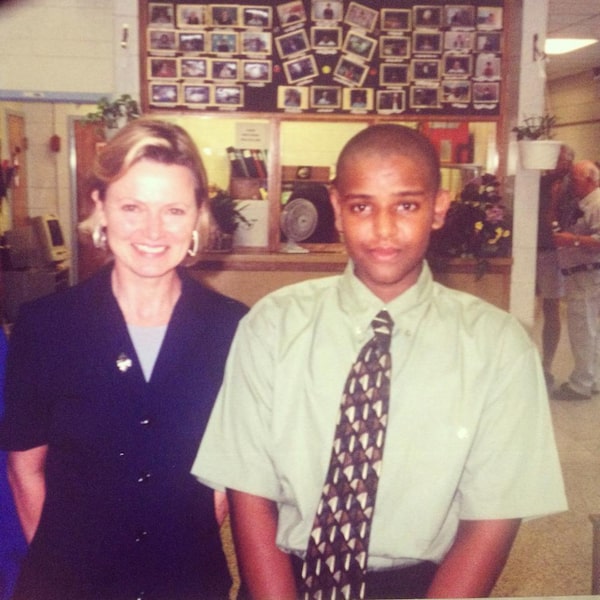

Elamin Abdelmahmoud in eighth grade, the year he arrived in CanadaElamin Abdelmahmoud/Handout

I related to the parents better: Their Arabic was still instinctive. I could talk to Sudanese parents in Kingston like we were running into each other in Khartoum. They had a muscle memory for the belly laughs and the keifaks and the way Sudanese greetings go on and on and on.

The Sudanese kids, welcoming as they were, tried their best to swish the Arabic words in their mouths. Their parents had told them to take it easy on me, so they collectively pooled all the words they knew and brought them to me as an offering. But I could tell that even though their parents had spoken Arabic to them their whole lives, and their homes were decorated with heirlooms of Sudan, they wore their Sudanese identity like a sweater that didn’t quite fit. They identified with something else.

That something else, as it turned out, was Blackness. I found this out when I visited a cousin living in Toronto. She was effortlessly cool, and had arrived in Canada four years before I did. “I don’t know why your Baba chose Kingston for your family,” she said. “Over here, we’re Black. And being Black in Canada is way harder in a place like your city. You’ll see.”

The words over here, we’re Black rang around my head. Before I could ask the million questions that swirled in my brain (Wait, what do you mean we’re Black? Does it come with rights and responsibilities? Do I get a card?), she handed me two CDs: The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill and Illmatic. “You won’t be around a lot of Black people,” she told me. “But hip hop can help you connect to them.”

I tried to like hip hop, which was an attempt at buying Blackness. (I’ll have one (1) Black identity, please.) But there was one problem: I couldn’t see myself in it. I’d grown up in a conservative Sudanese home. I was as prim and proper as they came.

Everything about my life in Sudan (religion, private school, wealth – pick one!) told me to run away from the world of hip hop. So that’s what I did.

Elamin Abdelmahmoud and his father.Elamin Abdelmahmoud/Handout

Part of the reason it was so hard for me to compute that I was now Black in Canada was because I grew up with my primary identity being Arab. We were Arabs, we told ourselves.

Khartoum prides itself on its contributions to Arab culture, from novels to singers to actors. Independent Sudan constructed its identity around Arabness, and access to the Arab world. The religion of the Northern elite, Islam, deepened Sudan’s ties to other Arab and Muslim nations.

Though there are dozens of regional dialects, Arabic is Sudan’s official language. Not that I knew any of this when I was 12 and living in Khartoum: Being Arab was the water I swam in. I couldn’t tell you what it was like outside of that water.

I rarely thought about my skin colour. I just didn’t have to. I knew that my complexion came from the mixing between Arabs and Africans that had dominated most of Sudan’s history. And I knew that my family had social standing.

The skin colours I did think about were those of Southern Sudanese people in Khartoum. They were “Black”: Their skin several shades darker than mine, they spoke Arabic with hesitation, and they were clearly not like us. So when grappling with the notion of being Black in Canada, this was my only reference point. That’s Black, I thought to myself.

This designation, unshakable in my mind, carried all kinds of weight and connotations. Casually, we’d call Southern Sudanese people living in the North horrifying names like abeed, or “slaves.” The elaborate racism of the Northern elites often excluded Southerners from the job market, from housing, from security. Though in reality they were economic migrants, tormented by circumstances specifically created by various governments in the North, the racist narrative I heard growing up was that they deserved their lot. That they were heathens for not becoming Muslims. They were unjustly blamed for thefts, rapes, murders and every plague that haunted Khartoum. Occasionally, local governments would promise to end the flow of these migrants coming north.

In the midst of unrelenting racism, Southern Sudanese people worked low-status jobs with no security. Most often, they worked as khaddams (servants). Though theoretically these migrants chose the labour, in reality they were beholden to the families who employed them for economic security and, sometimes, living accommodations. You rarely saw a Northerner working as a khaddam. I overheard families speak of lending each other their khaddam: “Oh, I’ll send my girl over to help with your wash,” they’d say.

You might think we had one or two khaddams during the 12 years I lived in Sudan. I remember five. Four were a family – twins Sandra and Sally, and their two younger sisters, Kelly and Kristine.

Elamin Abdelmahmoud with his mother.Elamin Abdelmahmoud/Handout

Sandra was Mama’s go-to. The oldest of the twins by four minutes, she occasionally lived in the separate room we had at the back of the house, sometimes for weeks at a time. Her day often started with sweeping the front courtyard, until Mama called her inside to give her another task.

On occasion, Sandra brought her sisters along for the work. From time to time, they’d set up the daybeds – extra beds we had for when it was nice outside – and they’d sleep in the courtyard or on the spacious balcony. Kelly was closest to me in age, just a couple of years older, and I found myself asking her to play often. Sandra would interrupt her work to give Kelly a glance, in what I understood later to be a warning not to get too comfortable.

Though I rarely had to think about my skin colour, I do remember one night that it was top of mind. When I was 10, after a particularly joyful evening of playing with Kelly, I asked Sandra if I could join the sisters in sleeping on the balcony. A cool breeze was blowing, and I loved sleeping outside on such nights – and besides, we weren’t done playing yet.

Sandra hesitated, and Sally chuckled at her hesitation. I lay in one of the daybeds and looked over to see Kelly spread out on her bed, the moonlight a gentle silver beam on her skin. I noticed that her skin and mine did not glow the same under the moon: Its beads pooled on her arms and gave off a gorgeous reflection. Mine absorbed the light, ate it all up, and gave little back.

As I began drifting off to sleep, Mama’s voice punctured the laughter, polite but firm. “It’s time for you to return to your bed,” she said, in a tone that didn’t leave room for negotiation.

“But I’m having fun, Mom!”

“Now.”

As I groggily left the balcony and headed to my room, Mama called back, “Have fun, girls!”

I could hear Sally’s distinctive laughter at the awkwardness of the whole thing.

Years later, I remembered how the moon had kissed Kelly’s skin. That’s Black, I thought to myself. And I am not that. So I dug my heels in, and refused to believe there was anything for me in Blackness.

A world away, I trained my ears to listen to how white Kingstonians talked. Not that I had much of an option: They were everywhere. I became a devout fan of wrestling because I overheard two students talking about how much they loved it. I listened to the rock radio station, because they spoke like the people I was trying to mimic.

I ran away from anything I saw as “Black.” This extended even to my name. In early high school, I was volunteering as a stagehand for the school’s talent show. After I set up the microphone incorrectly, one band’s singer apologized to the audience as he was readjusting it, and jokingly said, “Stan the Microphone Man set this up wrong.”

For years after, everyone called me that. At first, it was the whole phrase. Then, gradually, I just became Stan. I began introducing myself as Stan. What a perfect escape vehicle – no one ever suspects a Stan to be Black. Right now, if you flip to page 76 of the 2004-05 Bayridge Secondary School yearbook, you’ll read in my graduate goodbye that “for as long as I live, I shall forever remember my real name, Stan the Microphone Man.” My real name.

“Stan” was a gateway. It was an identity that manifested non-Blackness for me, which is another way of saying it approximated whiteness. “Stan” was the vehicle with which I turned away from the Blackness I saw on TV. Seeing Blackness on TV and then nowhere else meant that, for me, being Black in the West was an absolute, fixed thing, and I was not it.

But just because you want to walk away doesn’t mean you can. It’s not up to a person in a Black body to decide not to be Black. Just as Southern Sudanese people in Khartoum couldn’t escape the meaning attached to their skin in that context, I couldn’t escape it here. The Blacks of Sudan and the Blacks of the West carry the implications of their skin colour in the same way.

So Stan, the kid who listened to Linkin Park and watched wrestling, couldn’t choose not to be read as at least a little Black. This came out in throwaway comments from white friends, like, “Well, you’re Black but you’re not really Black.” The implication here was: I recognize that your skin colour is dark, but you are not exhibiting the other symptoms I associate with Blackness.

To be sure, I received “you’re not really Black” as a compliment. I cloaked myself in the superiority of it. It made me feel good to hear this; it was a way to note the distance between me and what I saw as a negative force.

What “you’re not really Black” connotes is comfort. Sure, I look like this, but I could be introduced to your parents. White dads loved me because I spoke like they did, listened to the same music they did (Kingston’s best rock, 105.7), and they didn’t have to stretch any muscles to talk to me. We could bond over the Rolling Stones. Oh, you’re a Beggars Banquet guy? I’m an Exile on Main St. man myself.

There’s a name for this: You’re an Oreo – Black on the outside, white on the inside. The politics of being an Oreo are familiar to all the Black kids who have had to grow up in predominantly white spaces. All the elements that make up your everyday life, a life lived in proximity to white people, are used to demonstrate how “white” you are.

Here’s the thing – I loved being called an Oreo. I relished the suggestion that somehow, beneath my skin, my internal workings resembled whiteness. This was a win. But this was not a new feeling. It was the same feeling of noting the difference between my skin and Kelly’s skin, and realizing mine held power.

Under the same graduate goodbye in that same yearbook, among the slew of nicknames I picked up throughout high school, I proudly list it: “Oreo.”

Everything I knew about being Black went out the window when I got to university.

In my high-school graduating class, there were three Black students, including me. The school had 10 Black kids in total. But just across town, on the campus of Queen’s University, I met a whole new universe.

Queen’s had more Black people than I had ever seen in Canada up until that point. And not just Black people, but people of all races – a kind of diversity I had never encountered in the suburbs of Kingston, just a few miles west.

Elamin Abdelmahmoud attended Queen's University in Kingston after graduating high school.Elamin Abdelmahmoud/Handout

Queen’s has a reputation as a particularly white institution. But in the fall of 2005, to me, it might as well have been the biggest, most diverse metropolis on earth.

In my first week of university, I introduced myself as Stan. New people, new place, new contexts – where better to go full mimicry, skip the hybridity dance, and just complete the blending in, right? I felt a little part of me sting but a bigger part of me swell with joy every time I beamed and said, “Hi, nice to meet you, I’m Stan.”

Occasionally, I got puzzled looks, and from time to time I’d clarify: “My name is Elamin but I go by Stan.” Usually that ended it. The passing was complete. I didn’t have to confront my ideas about Blackness because I was Stan, the guy who spoke English the way white Kingstonians do. My go-to party trick was sharing how long I’d been in Canada, and the fact that I’d just learned English a handful of years ago.

This trick, by the way, worked every time. Recognition that I was passing fuelled me, and when I deployed that ol’ move, I got a decent refill. The faces on white people. “You speak English so well,” they’d say. They meant: You speak English like I speak English. What a high.

It was all going swimmingly. Sure, I saw the Black faces around campus, but I didn’t have to do the work of squaring these new modes of Blackness with my deformed image of what Blackness was. That is, until I met Chantel.

The first time I met Chantel, she walked right up to me, with the biggest smile on her face, and handed me a new edition of a small zine called CultureSHOCK! It was filled to the brim with prose and poetry and paintings of people whose names were mouthfuls like mine. They wrote about their skin, which was like mine, and their attempts to blend in, which were like mine, and their attempts to fight, which were nothing like mine. They strung together words that stung – words that laced my heart with a pain of recognition.

That day, Chantel held the zine in her hands, smiled, and said, “Join us.” I didn’t understand then what a profound act of generosity this was; to see another person as a part of your tribe when they don’t see themselves that way is an act of kindness. It requires that you extend yourself to another.

I’m not sure Chantel and I ever exchanged more words than that for the rest of my university career. But like the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon, where you notice something and then start seeing it everywhere, she became a constant. She was in the cafeteria, handing out flyers for an anti-racism rally. She was in the street, asking people to sign a petition to force the administration to hire more non-white professors. She was in the school paper, fighting the student government.

She was far from the only match, but she was the most visible match to me in the powder keg that was Queen’s University in 2005. I didn’t know it then, but campus had a problem, and it was about to erupt.

Just a few months after Facebook became available in Canada, and one month after my first year started, a second-year student decided to dress up in blackface as Miss Ethiopia for Halloween. The photos quickly spread online until it became the talk of the campus.

But that particular racist act was happening on top of a bigger problem: Just a few years earlier, six faculty had quit the university, citing racism. Queen’s had then invited Dr. Frances Henry, a professor from another university, to examine race issues at Queen’s.

The Miss Ethiopia incident made national headlines just as the university was grappling with the extensive report, dubbed simply the “Henry Report.” It found that only 117 professors out of 1,378 faculty members identified as people of colour and/or Aboriginal. Dr. Henry went on to point out a few other issues with Queen’s: For starters, it had “Eurocentric curricula.” But the big takeaway was that the university had a “culture of Whiteness” – Dr. Henry concluded that Queen’s had an environment in which “white culture, norms and values … becomes normative and natural. It becomes the standard against which all other cultures, groups and individuals are measured and usually found to be inferior.”

Wheeeeew. So you’re telling me that the campus where I’m seeing more Black people than I have anywhere else in Canada actually doesn’t have enough Black people? I found myself in the middle of a tempest over race, after years spent avoiding it.

Moreover, Chantel was surer than me that I was part of an “us.” Her confidence was infectious. She was so sure that it punctured through my unwillingness to think about what I was taking in. For the first time, I looked around and saw one million iterations of Blackness, as real as I was, staring back at me. Nerdy Black people and jock-type Black people and intellectual Black people and theatre-geek Black people and business-school Black people and law-school Black people and conservative Black people. Black people who came from cities and villages, from other ends of the country and from other continents. All the possibilities I’d associated with whiteness, stretched to encompass Black bodies all at once. Bodies that included mine, its place now obvious in a gorgeous mosaic of Blackness.

Through Chantel, and through a conversation about race so loud I couldn’t tune it out, I learned that you can create a world so white, you cannot even see how white you’ve made it.

Elamin Abdelmahmoud.Kyla Zanardi/Handout

I became Black the way a person falls asleep: slowly at first, then all at once.

Black kids born in the West have their whole lives to wrap their minds around the identity. This is not to say it comes easy to them, if it comes at all – it’s just to say that, by arriving later in life, I was at a bit of a disadvantage. I spent 12 years never thinking about it, and several more outright rejecting it, so they had a slight head start.

Being Black felt, to me, like a deliberate constellation of tastes and aesthetics and lineage, and I had no access points to them because I did not know the history. Blackness, after all, is a learned biography, a book you have to read, though some of us have only watched the movie. Living in a Black body is a starting point of inheriting Blackness, but there is a rich archive of thought, art and politics to get caught up on.

It’s further complicated by the omnipresence of American Blackness, and particularly the one-dimensional story of Blackness that dominated pop culture in the early aughts; trying to take in the contours of Black life in Canada and Black art in Canada while tuning out the loudness of America’s cultural force is nearly impossible.

Still, I had names to learn, events to memorize. Was there going to be a pop quiz on this stuff? Did I need to know Choclair’s birthday?

I started with what I knew: words. Writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates introduced me to the way Blackness colours politics and economics. George Elliott Clarke gave a sense of history and place to Canadian Blackness.

But music is where it all started to sing. I was lucky enough to be born in the time of Beyoncé, and my Blackness came of age as she dove deeper into hers. Talib Kweli and Mos Def filled in some of the rest of the picture. Kanye West did, too. I finally went back to Illmatic and The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill and got what I was missing. “Everything is everything,” she told me, and it felt like a homecoming.

I listened to these artists, and when they referenced other artists, I wrote down the names. Every footnote led to another artifact. These rivers led back to the sources you’d expect: Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Nina Simone, Langston Hughes, Muddy Waters. I spent time with artists who love Black people, who love being Black, who invest energy into the maintenance of Black history. “I arrived on the day Fred Hampton died,” Jay-Z rapped, and onto Google I went to look up who that was.

What I was finding weren’t just keys to understanding the puzzle of being Black in the West. They were tools for undoing the years of colonial thinking I’d been led to believe for my entire life.

When, years later, I asked Mama why we’d called Southern Sudanese people abeed, she cringed with her whole body. She told me the shadeism I had grown up with would make us backward people in modern-day Sudan, which is trying to move beyond such blatant racism.

What I am trying to say is: It is possible to reform your idea of yourself. It’s the only real inner work there is – going back and revisiting your horrors, and holding yourself accountable and moving forward.

It is not your choice if your mind is colonized. But it is your choice to confront it. My diasporic wound is that I am still feeling my way around Blackness. Internalized white supremacy is not the n-word and the pointy hats; it’s the wobble in your step, the doubt in the back of your mind.

I do not see with one eye. I do not speak with one tongue. It took two stopovers and 19 hours of flying time for me to become Black. It took a years-long war with myself to realize I’ve never been anything else.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.